Have certain photographs ever caused an indescribable feeling in you? If so, you’re not alone. For Roland Barthes, the best photographs were able to wound the onlooker. But what exactly is this ‘wounding’ mechanism? And why does Barthes believe it relates to death? In this article, we’re going to follow Barthes to the root of what makes photography a discipline in its own right.

Photography Before Roland Barthes

For much of its short life, critics saw photography as a tool in service of its subject matter – as a means to an end. Criticism at this point focused on two main modes of analysis. Either, photography was analyzed in relation to the image it captured – be it a historical event, advertisement, or fashion – and its relevance to society. Alternatively, criticism focused on its technical aspects.

Critical discussions centered on historical trends such as pictorialism, or on genres, such as landscapes and photojournalism. Photography was thus never seen as a medium, or an end, in itself – unlike film or literature.

It was in this critical context that the French philosopher Roland Barthes published Camera Lucida in 1980, answering the very question that had not yet been properly asked:

What is the essence of photography?

In other words, what is the element that unites all photographs, and distinguishes the medium from related areas, such as cinema?

What Makes a Photograph Different?

Barthes began his investigation by finding out what photography was not – by seeing how it differed from related disciplines.

Photography as a Mechanical Process

Barthes’ investigation started in an earlier essay, ‘Rhetoric of the Image’ (1964), in which he made the crucial observation that:

‘[A photograph is] captured mechanically, not humanly.’

Take painting as an example. When a painter sits before a bowl of fruit and begins to put paint onto their canvas, the final image that comes out is a human interpretation of reality. The bowl of fruit is captured ‘humanly.’ The painter takes the real, and transforms it into the unreal, in the act of interpretation.

When the photographer, on the other hand, clicks the shutter-release, the process is purely mechanical. There is no artistic transformation of the real into the unreal, as the photograph is a literal reproduction of reality. Of course, there is an art to getting the composition of objects right, as well as in the editing process, in which light and color can be distorted for artistic effect. Yet, even if these elements can be influenced, the photographed object remains a real, fixed point of reference. And thus, the photograph continues to be a mechanical copy of reality.

In this sense, we can say: paintings represent, while photographs present.

Photography as Pre-Cultural

With this in mind, Barthes (1964) made another observation:

‘Photography is a message without a code.’

This might look more complex at first, but the concept can be broken down.

Look at a novel, for example. In a novel, the text (the word choice, the structure) is the ‘signifier.’ And the objects, people, and events that the text describes are the ‘signified.’ The way the author represents (signifies) the people and events (the signified) in their novel is determined by their own creativity. In other words, they can influence the signified as they so desire. Therefore, we can say that there is an open relationship between the signifiers and the signified in a novel. And due to this open relationship between signified and signifier, there is room for various interpretations.

However, in photography, the relationship between signifier and signified is different. As we’ve already established, a photograph is ‘captured mechanically, not humanly.’ It’s an exact copy of the real. Thus, the signifier is the signified. In other words, this photo of an apple signifies this apple that was photographed. It doesn’t represent but rather presents. The gap between real and unreal, object and representation, from which we can posit various interpretations, doesn’t exist in photography. As the reality of the photographed object is fixed, so too is our interpretation of it.

Can a Photograph be Interpreted?

Now, if Barthes had left his analysis here, there would be a very damaging implication for photography.

If photography is simply a brute record of what is/what was, then the image is nothing more than a mirror of reality and has nothing to say – no interpretation to derive. Culture necessarily comes before interpretation. Thus, if photographs have nothing to say, then they are pre-cultural artifacts, as interpretation is culturally influenced.

Therefore, we can no longer interpret the meaning of photographs as to do this is to impose a cultural attitude, and thus misunderstand their very nature (i.e. as being pre-cultural).

This is indeed damaging for photography as an art form. Yet, this conclusion contradicts our own experiences of photography, and the intimate meaning we read into them. So what is to be done?

Roland Barthes offered a solution. The lack of a code, he argued, becomes the very code of photography. That is, the signified meaning of a photograph becomes objective, as the thing photographed is necessarily real. Unlike a painting, whose landscape could be imagined, the object of the photograph must necessarily exist. This superimposes reality and the past onto the photograph, contrary to cinema and literature.

This, Barthes concludes, is the unique element – the noeme, as he calls it – of photography: that it captures ‘that-has-been,’ and that what it signifies is necessarily real.

The Experience of the Subject

When we pose in front of a camera, Barthes (1980) says we experience ourselves in four different ways. At once, we are the person:

- We think we are

- We want others to think we are

- The photographer thinks we are

- The photographer uses for the purpose of his art

As a result, we tend to feel inauthentic when posing for a photograph. It is as if we experience a mini identity crisis every time before the lens. As described by Barthes (1980) himself:

‘I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object: I then experience a micro-version of death.’

This ‘micro-version of death’ is a key concept for Barthes. Death is a fundamental element of the photograph for both the subject and the spectator. This idea will be further analyzed later. For now, let’s turn to the experience of the spectator.

The Experience of the Spectator

When locating the essence of photography – ‘that-has-been’ – Barthes focused on the experiences of the ‘spectator.’ The spectator is the person viewing the photograph. For the spectator, there are two separate elements in a photograph:

- The studium;

- The punctum.

Let’s now look at these two Latin concepts.

The ‘Studium’

According to Barthes (1980):

‘The studium is that very wide field of unconcerned desire, of various interest, of inconsequential taste.’

Put simply, the experience of studium results from a certain cultural knowledge that allows us to identify:

- The intentions of the photographer;

- The implications of the photograph.

My education, as given to me by culture, allows me to see every photograph as an example of something.

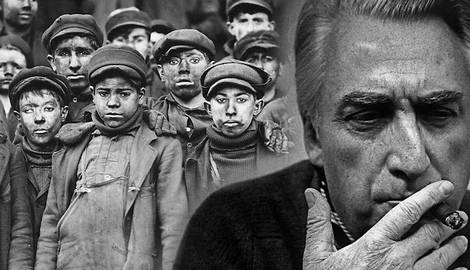

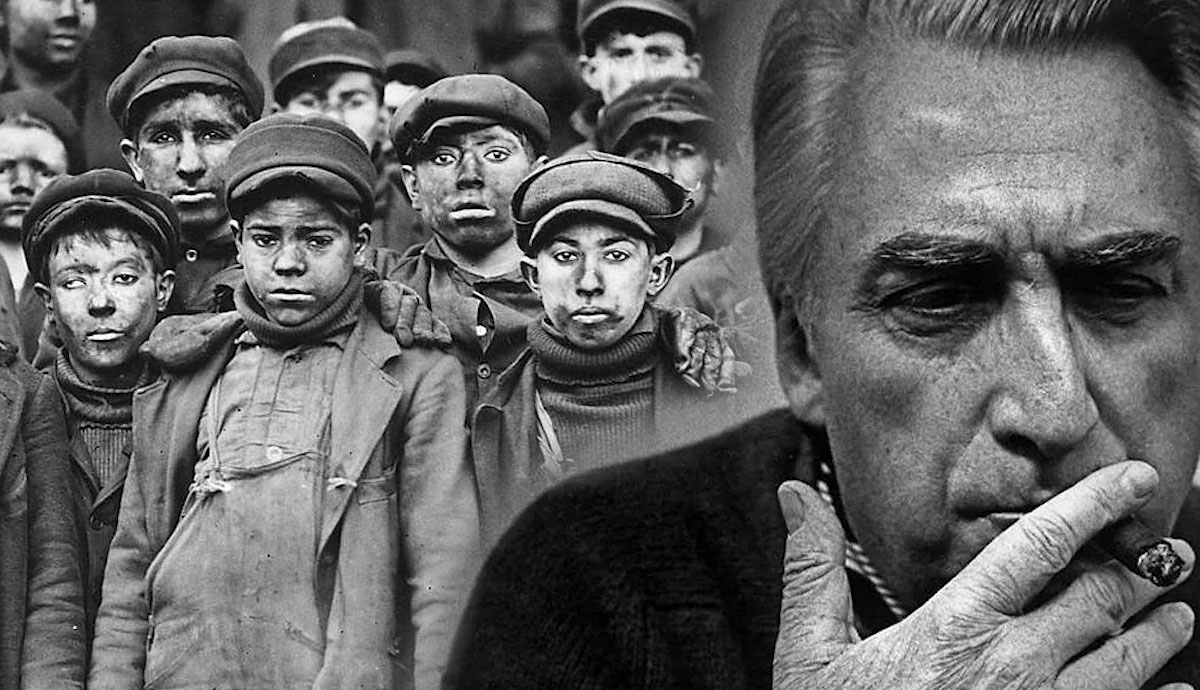

For instance, a photograph depicting poverty and child labor may stimulate my broad interest in inequality, and indicate the intention of the photographer – such as that the economic system was/is in need of change. The photograph, in this sense, appeals to the studium – it requires a certain knowledge (the result of culture) and appeals to this knowledge as exemplifying a case of something.

The studium operates at two levels of meaning: the denoted and the connoted.

Denoted meaning is simply the very object it captures: this apple, that king, the poor.

Connoted meaning, on the other hand, is that which the photograph implies in its symbolism: for example, that the poor live under an oppressive regime, in need of change.

The ‘Punctum’

The studium is intentional. The photographer knows that by photographing a specific scene, with a specific composition of people and objects, they appeal to the studium.

A particular photograph that captures the injuries and plight of civilians in war serves as an example of the generalized notion of the brutality of war – a cultural notion. Here, the denoted and connoted meaning is obvious.

In contrast, the second element of a photograph is accidental – the photographer does not intend it to be there. This is known, according to Barthes, as the punctum.

‘Punctum’ in Latin refers to that which ‘stings,’ ‘cuts,’ or ‘wounds:’

‘A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).’

(P. 27)

In Camera Lucida, examples of the punctum range from a man’s unkempt fingernails, to a boy’s oversized collar. These are all incidental features that cause an unexpected reaction in the spectator.

The punctum is non-obvious, accidental, and evokes a deeper emotional response in the spectator. It is thus the very element that attracts us to certain photographs, and is beyond denoted and connoted meaning.

Very broadly, we could say that the studium appeals to the intellect, while the punctum appeals to the emotions.

On top of this, the punctum is:

‘What I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there’ (Barthes, 1980).

There is a paradox here. The punctum requires the spectator, yet it exists independently of them, as it is ‘already there’ to be discovered. So, is Barthes simply identifying his personal subjective experience of photographs as an element belonging to them, rather than one he brings to it?

The short answer is no. Barthes saved his problematic definition of punctum by arguing that we can relate back to photography’s essence – ‘that-has-been.’

Roland Barthes: Photography, Time, and Death

In the second part of Camera Lucida, Barthes introduces a new variation of punctum, which is time itself:

‘This new punctum, which is no longer of form but of intensity, is Time […] its pure representation.’

The idea of time is present in every photograph. It is said that a photograph freezes time, but in reality, it’s a reflection of time’s constant, unrelenting nature.

When we look at a photograph of a relative, we know – given the essence of photography (‘that-has-been’) – that this person did indisputably exist. Yet, viewing this photograph in the present, we are reminded that this person will die or has already died. And further, we realize that this present, in which we view the photograph, will likewise become the past of the future, and that we, too, will die. Every photograph thus combines past, present, and future, embodying time and implying death:

‘Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe’

(Barthes, 1980).

This variation of punctum – as time itself – transcends the subjective experience of the spectator.

On the one hand, it exists independent of the spectator: the photographed subject did exist, and will one day die. And on the other hand, it is what the spectator adds: they see the ‘imperious sign of [their] future death’ (p. 97) in this intersection of past, present, and future.

Thus, the punctum is the consequence of photography’s essence (‘that-has-been’), and is indeed what is already there, in addition to what the spectator brings.

Conclusion: Photographs are wounding. Their accidental details – those which are outside the intentional narrative – are the elements that capture our emotions. And beyond the subjectivity of our emotions, it’s the unifying theme of time, and its implication of death, that truly wounds us. So the next time you find yourself lost in a photograph, think back to Barthes, studium, and punctum, to better understand that indescribable feeling.