The famous American artist Romaine Brooks spent most of her life in Europe, becoming one of the most remarkable yet rarely mentioned artists of her time. She was a member of a very specific group that could emerge only in modernity—the group of financially and socially independent queer women who were able to escape the constraints of society. For them, she became the careful and silent observer, creating a collection of works that formed a collective portrait.

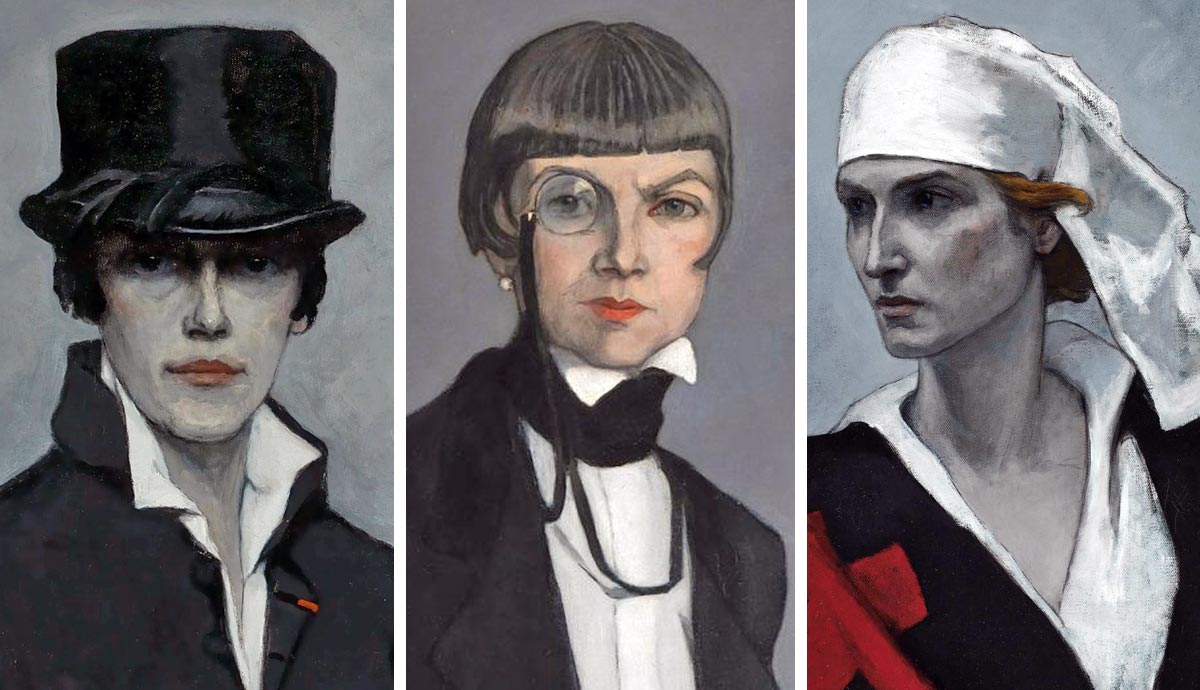

1. Self-Portrait of Romaine Brooks, 1923

Beatrice Romaine Goddard, who would become known as Romaine Brooks, was born in Rome to a rich American heiress traveling through Europe. Her childhood was formative for her career and life choices, but not in a good sense. Financial freedom and affluence were compensated by the violent and hysterical temper of the artist’s mother, as well as the disturbing behavior of her mentally ill brother. Brooks’ mother was completely absorbed into her son’s life and disliked Romaine because of her good health and mental stability.

During her early years, the artist experienced physical and mental violence. Drawing was her only way of self-expression, yet she had to hide scraps of paper from her mother to avoid being severely punished. The strategy of complete emotional withdrawal was the only way of surviving and keeping sanity for the young Romaine. Such detachment later formed her unique way of addressing her artistic subject matter—cold, reserved, and devoid of excessive detail.

Hardly ever interested in men, Romaine Brooks received her famous last name from a brief and unpleasant lavender marriage to British scholar John Ellingham Brooks. Despite purely practical reasons for that union, it did not last long due to John’s temper and inadequate spending habits. A year later, the fake couple divorced, with Romaine retaining her last name and leaving the ex-husband a generous yearly allowance. In the following years, she would travel the world and become one of the most acclaimed women artists of her time.

2. White Azaleas

The signature style of Romaine Brooks’ paintings began to form well before she started her series of society portraits. First, there were images of women—often nude and mostly her lovers—set in neutral interiors. In the austere palette of grays and blacks, white flowers become the only and necessary light source. The composition referenced the famous and scandalous Olympia by Edouard Manet, but with a twist that defined the oeuvre of Brooks. She took the traditional subject matter known for centuries—a reclining nude found on the canvases of those like Titian and Goya—and recontextualized it by removing the male gaze. Brooks’ nudes are painted, observed, and desired by a queer woman who boldly settles herself into the larger art historical tradition, announcing her perspective as equally valuable and valid.

Over the years, Romaine Brooks would create a gallery of characters, mostly representing a specific class. These were wealthy (or at least financially independent) queer women who could afford to detach from the conventional realm of patriarchal tradition and live within a close-knit community. In essence, Brooks’ portraits presented another unique and remarkable realm of modernity, flawed yet functional, constructed by women for women, with its own rules, norms, and markers.

3. Cross of France

Romaine Brooks spent her long life rather unfazed by the majority of historical events, with the obvious exception of the two world wars. World War I started while she was traveling through Switzerland with her then-partner, Ukrainian-Jewish dancer Ida Rubinstein. Feeling genuine anger for humanity unable to resolve its issues at peace, Brooks channeled her irritation into productivity, setting up a fund for the French artists wounded on the battlefield. Ida Rubinstein, also a wealthy heiress, funded several medical programs. Brooks’ war effort resulted in one of the most famous paintings of her oeuvre, The Cross of France, for which Ida Rubinstein modeled. Dressed in the Red Cross nurse uniform, the dancer turned into the emblem of French patriotism and resilience.

4. The Crossing

The relationship between Brooks and Rubinstein did not last long. Ida dreamt of them living in a remote farmhouse in the French countryside, withdrawn from society and its conventions. However, this romantic concept was Brooks’ worst nightmare.

With Brooks, both emotional and physical intimacy were impulsive and short-lived and could not be transformed into a constant state of domestic bliss and cohabitation. She valued her personal space far more than anyone’s company and quickly got bored with people, despising the overwhelming majority of them. For her, Ida’s dreams of a country home were suffocating and threatening to her artistic integrity. Despite that, Rubinstein was one of the crucial figures in Brooks’ art life, opening her creative limits towards more mystical and allegorical subject matter. In stark contrast to Brooks’s other portraits, the images of Ida presented her not as a living being but as allegories and archetypes, as ethereal beings detached from physical reality.

5. Natalie Barney

For Romaine Brooks, no woman was more important than the American writer Natalie Clifford Barney. Barney and Brooks spend more than five decades in a non-monogamous relationship, despite the artist’s penchant to get bored by her partners and abandon them. An open and proud lesbian, Natalie Barney had many ambitions. She intended to create a center of the Sapphic cultural world under the name Temple of Friendship.

The emblematic figure for the Temple was the Ancient Greek poet Sappho, known for her poetry expressing love for women. Barney hosted Antiquity-themed parties where guests danced naked or dressed in Greek gowns in her garden among Greek statues. Her weekly Parisian salon gathered the most talented, influential, and remarkable queer women of her time, including Gertrude Stein and Sarah Bernhardt. The lesbian identity of Barney extended far beyond personal affairs: it was a way to build a community, a set of principles, and a theoretical and aesthetical lens through which the world was examined.

6. Una, Lady Troubridge

The portraits by Romaine Brooks had little in common with Barney’s refined vision of a Sappho-inspired utopian community. They were limited in tone and expression and served as a gallery of contemporary characters, with the artist’s lens not always working in the model’s favor. Among the most famous and remarkable images ever painted by Brooks was the portrait of a British sculptor Una Troubridge, who was mostly known for her relationship with the notorious lesbian writer Radclyffe Hall.

Hall’s scandalous novel The Well of Loneliness expressed the deep emotional turmoil experienced by queer women in a hostile society. However, Brooks was unimpressed by Hall’s attempt to publicly legitimize her sexuality through confessional autofiction, which Hall’s text essentially was. She was equally annoyed by Troubridge’s attempts to promote her partner’s writing genius.

In 1924, Brooks painted a portrait of Una, which finally turned their already strained relationship into a hostile one. A thin and stooped figure with a distorted face and a short haircut that looked like a badly fitting cap upset Una so much that she refused even to acknowledge that it was her portrait. Brooks never admitted her fault. For her, the portrait showed the essence of Troubridge’s persona and her public image, however unpleasant it might be.

7. No Pleasant Memories: The Unpublished Memoirs of Romaine Brooks

Among the most important works of Romaine Brooks was her unpublished autobiography. Titled No Pleasant Memories, it was a detailed, rather sincere, but carefully edited account of her life, relationships, and art. Brooks started to work on it in 1930, during the summer spent near Saint-Tropez. Annoyed by the swarms of guests continuously brought by Natalie, the artist locked herself in her bedroom and started to write out her disturbance. Brooks reflected upon her childhood in a household where delusion and insanity were the only norm, her haunting visions and the ill-fated romances all ruined by her destructive self-sufficiency.

The most offensive to Romaine, however, was the rejection of illustrations to the text. The fluid, almost Surrealist line drawings had little in common with Brooks’ other works. She regarded them as her most intimate expressions, as imprints of her unconsciousness, minimalist yet highly expressive. They convey violence, an overwhelming desire to control and possess, and deep fears that do not dissolve with age but rather condense and mutate into something even more horrific. Deeply disturbing and highly personal, some of the works evoke the guilt of accidental voyeurism.