After the kings were expelled from Rome and before the Julio-Claudians established the first imperial dynasty, the consuls were the most powerful men in Rome. This political position was designed to fill the power vacuum left by the Roman kings but in a more egalitarian manner, at least as far as the Roman elite were concerned. There were always two consuls so that no individual man could gain too much power. The position was so important that it continued to exist in imperial Rome, though it was more symbolic. This is a brief history of the Roman consulship.

Kingship in Rome

Plentiful written records and archeological remains mean that we have a good understanding of the history of Rome under the Republic and the Empire. The same is not true for the period of the kings. What we know of Rome’s kings is based on stories that were already considered legends during the Roman Republic.

According to legend, Romulus and his followers built the city of Rome on the Palatine Hill by the banks of the Tiber in 753 BCE, though it required killing Romulus’s twin brother Remus. Romulus’s followers elected him king of the new city, and then Romulus himself established many of its political institutions, including the tribes managed by the tribunes and the Roman senate comprised of 100 of Rome’s best citizens. They and their families became known as the patricians (aristocratic class), while the rest of Rome’s free population were plebeians. Over time, other classes would emerge such as the equites and freedmen.

There are different accounts of how Romulus died. Livy believed that he was taken to heaven by Mars to become a god himself. Romulus was later worshiped as the god Quirinus. But Livy also relates the story that he was killed by the Roman senate for his tyrannical behavior. They cut up his body and carried it away in small pieces so that there was no evidence of what happened.

Either way, the legend says that after a year during which the senate ruled in Rome, they elected Numa Pompilius, an Italian prince, as the next king in 715 BCE. This set a precedent, and the next four kings of Rome were elected by the people via the comitia curiata (popular voting assembly).

This ended in 534 BCE when Tarquinius Superbus used military force to overthrow the previous king and made himself a tyrant. He was tolerated for more than two decades before he was overthrown. While the turning point in his reign is linked to the rape of the noblewoman Lucretia by one of Superbus’s sons, this is just one example of Superbus not respecting the patrician class.

At the start of his reign, Superbus killed many senators who supported his predecessor and never replaced them, letting the senate dwindle in numbers and importance. While the rape offended many and encouraged them to join the cause, the real problem was that Superbus did not pay proper respect to Rome’s aristocratic classes.

Tarquinius was exiled rather than killed, and he did make some failed comeback attempts. But in 509 BCE, power in Rome was restored to the people, which meant the patricians. They now needed to decide how to fill the power vacuum left behind by the kings.

Power of the Consuls

Rather than completely revise their political institutions, the Romans seem to have simply decided to replace the king with a political office that would cover his essential responsibilities. But they also placed checks and balances on the office to ensure that no one man could accumulate too much power and create a new tyranny.

The office created was that of the consul, which was the ultimate step on the ladder of the cursus honorum, a sequential order of public offices. Two consuls were elected so that they could check each other and veto one another’s actions, and their period of service was limited to just one year. Initially, they could also only hold the office again after a break of ten years. They were elected by the same assemblies that had previously elected the kings.

The consuls assumed all the powers that the king had enjoyed. They had vast administrative, legislative, and judicial power. However, their judicial power was quickly diminished with the appointment of judges. While they could summon and arrest people, they could not summarily execute people in Rome.

Consuls could pass laws. For example, Marcus Acilius Glabrio made changes to the calendar in 191 BCE, Lucius Julius Caesar offered citizenship to Italians who did not oppose Rome during the recent Social War in 90 BCE, Cicero regulated election fraud when he was consul in 63 BCE, and Pompey and Crassus extended Julius Caesar’s proconsulship in Gaul for five years when they were consuls in 55 BCE. They were allies at this time, and this shows how the office could be politically valuable. The consuls also had the power to call meetings of the Senate and act as its presidents, and they had to realize laws decreed by the Senate.

The consuls received imperium, which gave them command over Rome’s armies. Traditionally they each had two legions under their command and would be deployed to different regions. If they needed to be together to face a particular threat, they would take control on alternative days. This ended up being a disaster at the Battle of Cannae against the Carthaginian leader Hannibal in 216 BCE. According to Polybius, while the cautious consul Paulus was moving strategically against Hannibal on his days when the reckless consul Varro was in control, he led unadvised attacks, undermining the greater plan. When they were triumphant, a consul could be awarded a triumph for their victory.

When their time in office was over, the imperium of the consul would become imperium proconsular. They would usually be sent off to act as a proconsul (governor) of a province, which would allow them to enrich themselves. They would exercise the same powers that they did as consul, but only in their province. They would usually serve for between one and five years.

That the consuls assumed the powers of the kings is evident in the trappings of the consulship. Like the kings before them, the consuls were accompanied in public by twelve lictores, who acted as an honor guard and bodyguards. The lictors carried fasces, which were a bundle of rods containing an ax that symbolized imperium. They would remove the ax when they were within the pomerium, which was the sacred boundary of the city. This reflected the fact that the power of imperium was limited within the city as the consuls could not violate the rights of citizens. When proconsuls returned to Rome, they forfeited their imperium proconsular the moment they entered the pomerium.

The consuls also took on some of the religious responsibilities of the kings. They were not the head of the Roman religion, this responsibility sat with the Pontifex Maximus. But the consuls were made rex sacrorum and were charged with conducting many rituals and sacrifices on behalf of the Roman state. This made them sacrosanct while in office, making it a crime to harm or threaten them.

Who Were the Consuls?

According to legend, initially, only patricians could occupy the position of consul. However, there is evidence that some of the earliest consuls came from plebeian families. Nevertheless, there was a law passed in 367 BCE explicitly granting plebeians access to the office.

This law seems to have made little difference to who actually served as consul. Only people from wealthy and powerful families with political backgrounds could claim the office, and most consuls could boast another consul among their ancestors. There were some novi homines (new men), who were the first in their family to occupy the position. Cicero was such a new man when he became consul in 63 BCE. But he claimed that there had only been around 15 consuls who were new men before this time.

Later, other rules were enacted around assuming the office. For example, Sulla regulated the ages at which men could assume different offices on the cursus honorum, which made the minimum age for the consulship 42 or 43 years old. This later dropped to 32 years old.

We know the names of many Roman consuls because they gave their names to the years for dating purposes. This means that their names survive on monumental inscriptions and in historical texts. Many inscriptions include passages such as “C(aio) Minicio Fundano et C(aio) Vettennio Severo co(n)s(ulibus)” [When Gaius Minicius Fundatus and Gaius Vettennius Severus were consuls]. If a consul died in office, he was replaced. That replacement consul was called a consul suffectus, and it was a less prestigious position because their name was not given to the year.

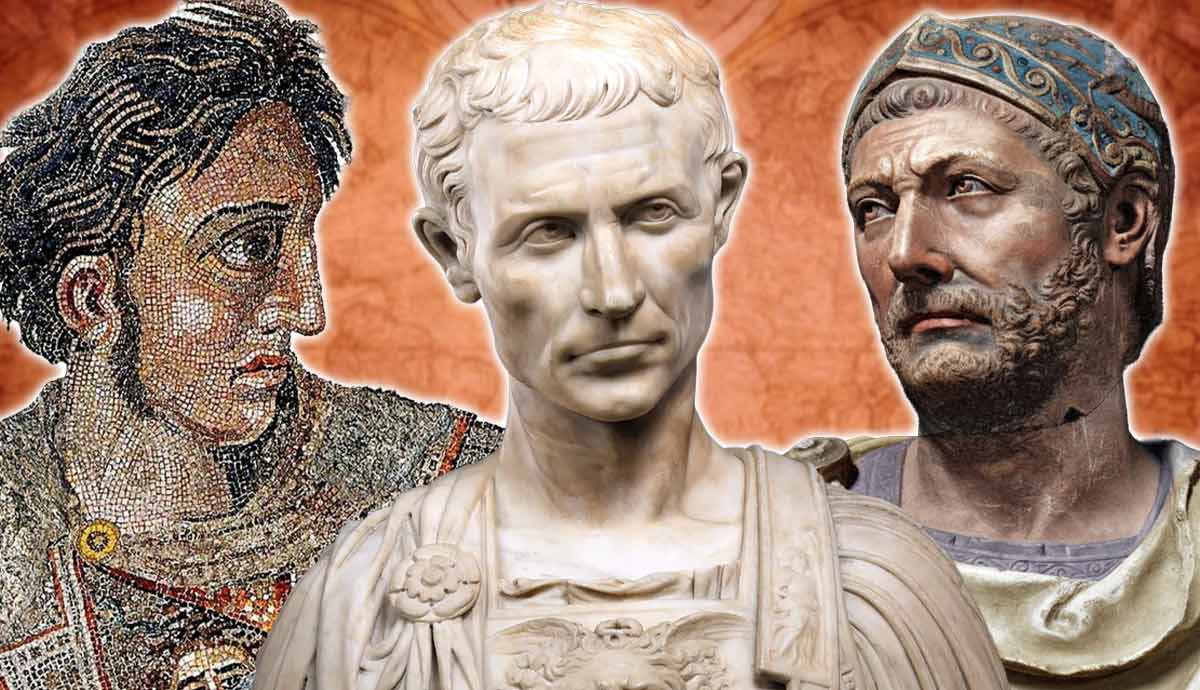

At the end of the Republic when politics became dominated by powerful generals, the rule that a man could only hold the consulship once every ten years broke down. The popular leader Marius held the consulship seven times, including for five consecutive years between 104 and 100 BCE.

Later, Julius Caesar would hold the consulship five times, first in 59 BCE, after which he became proconsul of Gaul. When his allies Pompey and Crassus were consuls in 55 BCE, they voted to extend Caesar’s proconsular powers there for another five years. At the end of those five years, he wanted to return to Rome but feared prosecution. Therefore, he wanted to be made consul so that he would be protected but was blocked by his former allies.

This situation triggered Caesar to march into Italy with his army and make himself dictator in 49 BCE. He used that power to secure the consulship for 48 BCE, at which point he resigned his dictatorship, suggesting that the consulship was more valuable to him. He campaigned in the east for the next few years and was then consul again in 46, 45, and 44 BCE. In 44 BCE he was also made dictator for life, which was the final act that led to his assassination by a group of senators for attempted tyranny.

The title dictator was never used again after 44 BCE. But as the Roman Republic transformed into an Empire, the consulship continued to be important.

The Consulship During the Empire

As Octavius Caesar was trying to establish himself as Caesar’s heir, he accepted the suffect consulship in 43 BCE, giving him the proconsular power to command armies in the provinces first against the conspirators that killed Caesar, and then against his former ally Marcus Antonius. He then held the consulship again in 33 BCE, following the ten-year rule.

Following his defeat of Marcus Antonius at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, as part of consolidating his power, Octavius Caesar, who adopted the title Augustus in 27 BCE, held the consulship consecutively for nine years from 31 to 23 BCE. By the end of this period, Augustus had consolidated his power in other ways and could loosen his grip on the consulship.

Augustus was granted imperium maius, giving him control over Rome’s military without the consulship. He was given autoritas superior, which gave him power over all other magistrates. He was given the right to convene the senate, and from at least 23 BCE he was awarded tribunicia potestas, making him sacrosanct and giving him the power to both pass and veto laws. In 12 BCE he became Pontifex Maximus, making him the head of Rome’s religion. Augustus acquired all the powers of the consulship, without having to hold the office.

Augustus could not afford to monopolize the consulship because he needed it as a pipeline for rewarding his supporters and qualifying them for important posts across the empire. For this reason, he also made it standard for the consuls to hold the position for just six months, at which point they would be replaced by less prestigious suffect consuls.

The increase in consuls, combined with the purging of the old patrician families at the end of the Republic and throughout the Empire, meant that more new men were able to become consuls, diminishing the prestige of the role. Nevertheless, it was considered the highest honor to serve as consul alongside the emperor.

The emperors would still claim the consulship and use it to signal succession. Augustus’s various heirs held the position throughout his reign. Tiberius followed suit. The year after he became emperor, Tiberius made his son Drusus consul to launch him into public life. Tiberius then shared the consulship with Germanicus in 18 BCE to signal him as successor. Germanicus died the following year, so Tiberius shared the consulship with Drusus in 21 CE to signal him as the new successor.

When Gaius Caligula came to power in 37 CE, the youth had no military or political experience, so he immediately took the suffect consulship to help establish his power. While he didn’t hold the consulship in 38 CE, he held it every other year for the rest of his reign.

After the civil war, when the Flavians succeeded the Julio-Claudians as the ruling dynasty, a member of the Flavian imperial family held the consulship for 20 out of 26 years as a strategy to consolidate their new dynasty. This pattern of behavior was followed by emperors for the next two centuries, until about 284 CE when the emperors became more autocratic.

During his reign, Constantine (306-337 CE) assigned one consul to be appointed in Rome and one to be appointed in Constantinople. Consequently, the consulship continued in both the Western and Eastern empires when the empire was divided at the end of the 4th century. There were still consuls when the empire collapsed in the 6th century.

While the nature and importance of the consulship changed throughout the history of Rome, it was always an essential part of the political landscape. First, it allowed the new republic to fill the void left by the expelled kings. It then allowed the emerging principate to create a basis for power anchored in Republican tradition, even if the real basis of imperial power was military might.