It is impossible to separate Christianity from the Roman context in which it developed and spread. Some of the influences the Roman Empire had on Christianity were negative, though it also strengthened the fledgling religion. In other ways, Christianity was well served by the vastness of the empire and the infrastructure it had in place. The effect of the Roman Empire on Christianity is recognizable to this day. From the Christian creeds to Papal titles, the fingerprints of the Roman Empire can be seen in Christianity.

The Roman Empire and Christian Origins

Jesus Christ lived and ministered less than a century after the death of Julius Caesar. At the time the Roman Empire stretched from the Middle East to Spain throughout Southern Europe and from Egypt to Mauritania in North Africa. A vast empire indeed. It was the Roman judicial power that allowed Jesus to be crucified at the hands of Roman soldiers, who also guarded the tomb where Jesus was resurrected. These two events are central to the Christian faith.

The Roman Empire was generally tolerant of other faiths, as long as they did not impede on emperor worship, a practice common throughout the Roman Empire. To people from polytheistic faiths, this posed no problem. To Christians, however, emperor worship was diametrically opposed to their monotheistic views. Christians, therefore, found themselves at odds with the Romans.

Saint Paul, on occasion, called on Rome when persecuted because of his faith. He could do so because he was a Roman citizen. This gave him the opportunity to minister in the capital of the empire before its rulers and the elites. As a Roman citizen, he could also freely traverse the Roman Empire on his missionary journeys which may have seen him travel as far West as Spain. Well-established Roman infrastructure in terms of road networks and merchant shipping would have made traveling to remote parts of the empire much easier. In this way, the gospel message was indirectly served by the Empire.

However, before long, the Roman persecution began, declaring Christianity illegal and utilizing a variety of tactics to force pagan converts to revert back to traditional Roman religion. Nero, for instance, led a persecution in which many early Christians were martyred. He executed both Paul and Peter and conducted indiscriminate slaughter of Roman Christians. They were scapegoated and blamed for the fire that destroyed much of Rome in 64 CE. Persecutions also continued sporadically on a local level, throughout the reign of Domitian 81-96 CE.

Later there emerged a series of empire-wide persecutions beginning with Emperor Decius, in 250 CE. Among other things, Christians were ordered to sacrifice to the gods. The persecution only ended when the empire itself faced the prospect of collapse.

The next and worst persecution of all was under Diocletian. During his reign, Christian churches were destroyed, Christian scriptures were burnt, clergy were imprisoned, and many were forced into performing pagan sacrificial rites. Christians were banned from holding state office positions and some who previously had were sent into exile.

The persecution had a similar effect to the Reformation persecutions many centuries later. It galvanized the faith of Christians and served as a witness to those who observed the faith of Christians being punished or executed.

Refining the Faith

Persecution was a significant force in strengthening the Catholic Church. It became apparent to early Christians that their faith was worth dying for and many Christians were called upon to defend their faith.

Initially, there was much diversity in Christian beliefs, as the apostles and missionaries spread Christianity throughout the world. However, the prospect of martyrdom forced Christians to solidify their beliefs. If Christians were going to die for their faith, it was essential to know exactly what they believed. It was under persecution that the early Christian creeds began to take shape because it was important that unity be maintained.

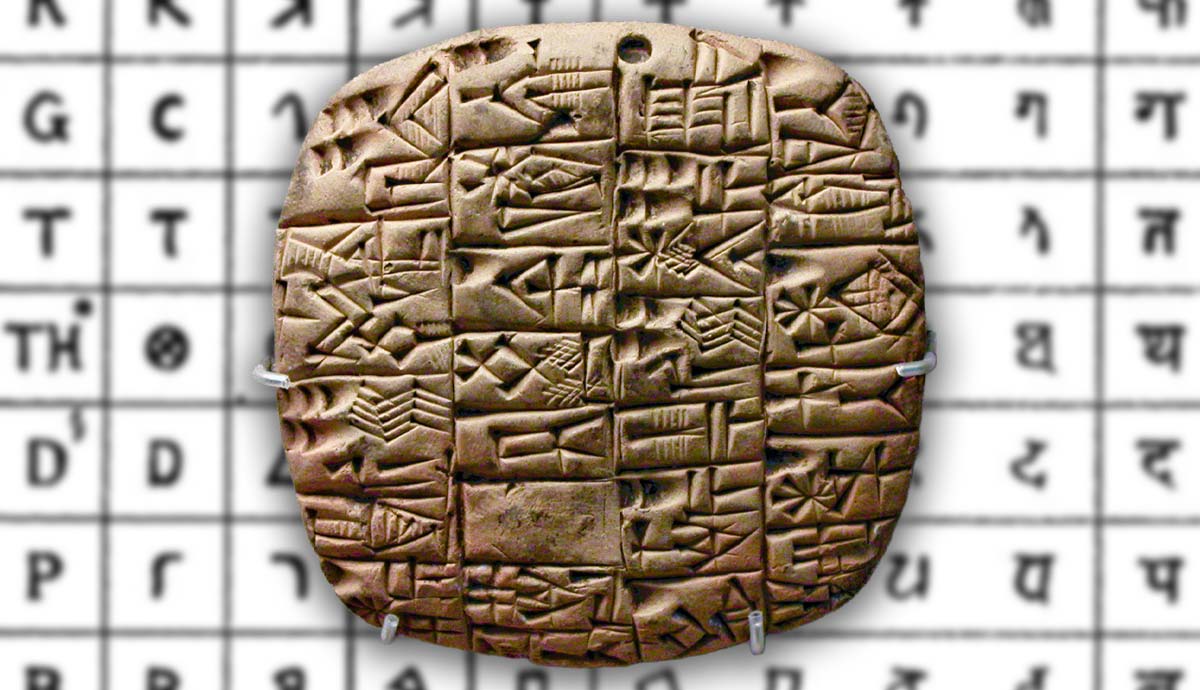

The Apostles’ Creed was based on the teachings of the apostles in the New Testament, and it lists the precise Christian beliefs. The need for statements of faith later gave rise to many councils where the church could develop creeds defining the core Christian beliefs. These creeds served to separate authentic Christian beliefs from those of cults and heresies. They were fundamental to the development of orthodoxy and unity within the Christian faith.

From Acceptance to State Religion

Constantine the Great was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity (though some scholars doubt whether his conversion was true). He supposedly did this after seeing a vision just before the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 CE. In this vision, he saw a cross in the sky with the words “IN THIS SIGN CONQUER.” After he became emperor, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, which accepted Christianity along with all other religions. In 330 CE, Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to its new seat in the East, Byzantium (later named Constantinople and today known as Istanbul, located in Turkey).

The decision to call the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, was a result of Constantine’s desire to have a unified Christian faith to help support his authority, not a result of Constantine’s own conversion. Nevertheless, it helped establish consensus on some aspects of the Christian faith. Only with the reign of Theodosius I from 379-395 CE did Christianity become the official state religion.

This change did not come without compromise. Christians had faced internal pressures to change certain aspects of their religion to fit better with Roman culture for more than a century before becoming the official state religion. Accommodations made included the introduction of a hierarchical leadership structure, a shift in the religion’s focus from symbolic acts to ritual acts, and a reinterpretation of the “love feast” (agape) into the “Eucharist” as the central ritual act of Christianity.

With the favor of various emperors and a new freedom from persecution, Christian leaders could quickly adapt Christianity to contemporary Roman cultural norms while capitalizing on the religion’s newfound ability to openly compete with alternative faiths. Staunch opponents of the Roman Catholic Church go as far as to call these compromises “baptized paganism,” claiming pagan feasts, statues, and rituals were reassigned “Christian” names and significance. They allege that these pagan themes thus entered Christianity.

From State to Church

Most scholars agree that Papal dominance in Rome happened gradually. According to the Donation of Constantine, a document many scholars believe to be a forgery from the 8th century, the emperor gave charge of Rome to the papacy in the 4th century CE. Whether this claim is true or not, it is evident that the papacy rose in prominence and power after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Many writers and historians have attested to this fact:

“Out of the ruins of the Roman Empire there gradually arose a new order of state whose central point was the Papal See.”

The Church and Churches, p. 42, 43.

“And if a man considers the original of this great ecclesiastical dominion, he will easily perceive that the papacy is no other than the ghost of the deceased Roman Empire, sitting crowned upon the grave thereof: for so did the papacy start up on a sudden out of the ruins of that heathen power.”

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, p. 436.

“While this Christian Church, little by little, was emerging from the general dissolution of the Roman Empire, there also emerged gradually at its head a new figure, the Pope.”

Coulton, Medieval Panorama, p. 20.

Since the popes claim lineage from Peter, who was martyred in Rome, it follows that they would prefer their seat to be located in that city, where the Vatican is to this day (although there have been times of turmoil in and outside of the Roman Catholic hierarchy when the pope resided Viterbo, Orvieto, Perugia, and Avignon).

The transition from the Imperial Roman Empire to Papal State is evident from the transfer of certain titles the Roman Emperor had, which were given to the pope — such as “Pontifex Maximus,” from which the term Pontiff arose. Pontifex Maximus means “greatest pontiff,” the title of the head of the College of Priests in the ancient Roman religion. Today, it is the title of the pope.

Roman Empire & Christianity: Conclusion

It would be impossible to comprehensively address the origins of Christianity without taking note of the influence the Roman Empire had on it. Some influences were negative, such as the persecution of Christians, though even these had a positive result. Having some Christians martyred for their faith, galvanized the faith of others, and caused Christianity to work toward establishing confessions of faith. These creeds helped differentiate between orthodoxy, heresy, and cult.

The Roman Empire provided the environment in which Christianity could move from persecution to recognition as the official State religion. Its vast empire and infrastructure also facilitated the quick spread of the Christian faith. Several scholars and historians see a continuation of the Roman Empire in the Roman Catholic Church, claiming the latter is a later, yet very different iteration of the former.