Ancient Rome unfairly has a reputation for having stolen or copied their mythology and religious traditions from the Greeks and given them Latin names to claim as their own. This is easily disproved by looking at Roman traditions in a broad sense but more specifically, it is disproven by the existence and omnipresence of a uniquely Roman god called Janus. Usually seen as just the god of doors, Janus’s role in Roman religion went beyond a simple case of Greek syncretism.

The Mythical Origins of Janus

Roman mythology was peculiar compared to its contemporaries. Greek and Egyptian myths are known for vibrant stories about the gods, the world around them, and why things are the way they are. The Romans on the other hand, were seemingly not as interested in telling these stories. The distinctly Roman myths that do exist tend to focus on the deeds of heroes and kings. It all served to glorify the state of Rome.

The handful of myths and stories written about Janus are typical of Roman mythology. Plutarch’s Parallel Lives has a book dedicated to Rome’s second king, Numa Pompilius. The purpose of this section of the book was to glorify a figure that shows the piety and duty that was expected of Roman citizens. In this section, Janus is referenced as being the name for the month of January, which King Numa placed at the start of the year instead of March, which was named for Mars.

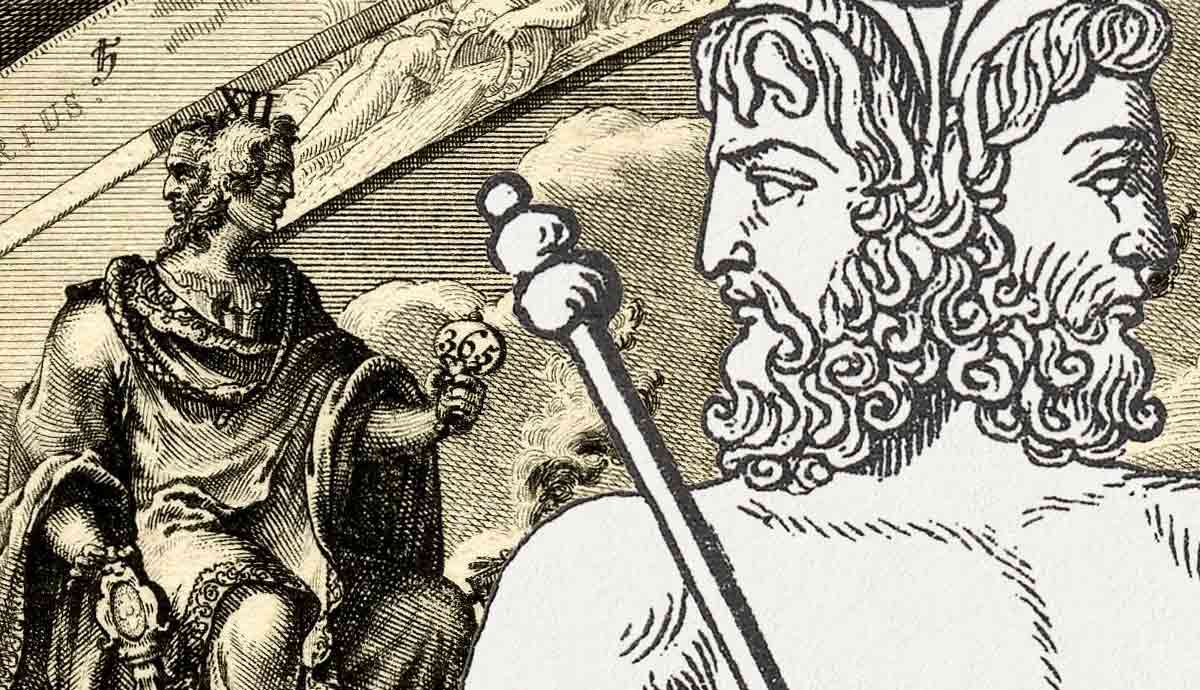

According to Plutarch, the reasoning was that Numa believed war must come after civil and political affairs in order of priority. He then clarifies that whether as a hero, demi-god, or king, Janus was associated with matters of the state, including most interestingly as the one who uplifted mankind out of a “bestial” and “savage” state. His two faces represent humanity in its two states: barbaric and civilized. In this version of the myth, Janus is the symbol of the connection between the divine and the profane, a duality that existed in all parts of the Roman state due to civic figures frequently doubling as priests.

Another variation on the story of how January was named comes from Ovid’s Fasti in Book 1. Similar to Plutarch, Ovid mentions Numa honoring Janus by creating a month named after him and placing it at the start of the year. When speaking of the Kalends (the beginning of the month) and its significance, the narrator of the Fasti claims to speak directly to Janus and asks him about his name. The god responds:

“The ancients called me Chaos (since I am of the first world):

Note the long ages past of which I shall tell.

…

Then I, who was a shapeless mass, a ball,

Took on the appearance, and noble limbs of a god.

Even now, a small sign of my once confused state,

My front and back appear just the same.

Listen to the other reason for the shape you query,

So you know of it, and know of my duties too.

Whatever you see: sky, sea, clouds, earth,

All things are begun and ended by my hand.

Care of the vast world is in my hands alone,

And mine the governance of the turning pole.

When I choose to send Peace, from tranquil houses,

Freely she walks the roads, and ceaselessly:

The whole world would drown in bloodstained slaughter,

If rigid barriers failed to hold war in check.

I sit at Heaven’s Gate with the gentle Hours,

Jupiter himself comes and goes at my discretion.”

Ovid goes on to explain that the name stems from the Latin word hiare, or “to be open,” which reflects the nature of Janus in this text as primordial Chaos and the shaper of creation. It is important to note that Ovid was not a theologian by nature. His works are literary and his purpose was to tell a story. Yet in spite of this, it is not as if he is simply conjuring up a story out of thin air. His works draw inspiration from other myths and legends, primarily Hellenistic ones, rewritten in a Roman context for a Roman audience.

So why then is Janus described in this way? Why is he described as being a master even to Jupiter, who as King of the Gods answers to no one? Greek religious practices have no equivalent to this. So where is Ovid drawing this from? The answer could be that he is drawing from older distinctly Roman traditions that have no Hellenistic counterpart. He is drawing on traditions that date back to before the period of Hellenization Rome underwent in the 2nd century BCE where they adopted Greek myths and traditions and pushed away their own prior ones.

The implications of Janus’s position here supposes a great deal about the nature of Roman religious traditions, even if by the time of Ovid and the Late Republic this nature had been mostly forgotten or was taken for granted.

The Use of Janus in Ritual in the Late Republic

While Ovid may have been calling upon older traditions that were known to the Romans in the Late Republic, Janus was not as openly associated with the imagery of a creator deity in other instances. There are two main areas where Janus was often invoked either in imagery or in word. The first area is the obvious one that bears relation to what he is associated with nowadays: doors.

Janus’s image was frequently put on doors or in doorways as a means of warding off evil. The most famous of these were the doors to the Temple of Janus in the Roman Forum. The temple’s doors were open during times of war and closed in times of peace, and the symbolism of the doors opening and closing was a means to bookmark each period of conflict.

But if Ovid is correct in his associations of Janus with creation, how does this connect to doors? The answer comes in the form of another question. What is a door symbolically? What do doors represent? They are a threshold, a transition between rooms, and between places. Janus is the god of doors, yes, but more importantly, he is the god of beginnings, transitions, and endings.

If something begins, Janus begins it. If someone is trying to move from point A to point B Janus protects the transition. If something ends, Janus ends it. He is every beginning and every ending. This duality is reflected in the nature of Roman prayer structures even in the centuries after conscious knowledge of Janus’s role slipped away into a hellenized interpretation of the gods.

Roman prayer is formulaic, just as other ancient polytheisms were. Orthodoxy or correct belief was not really a concern. Belief was useful and good, but it wasn’t the be-all and end-all of proper piety and religious behavior. What was important was orthopraxy or correct action. Prayers had to follow a formula if the worshiper wanted to get the proper results from the gods.

Unique to the Romans compared to the Greeks, Roman prayers did not begin with an invocation to the spirits of the home or the god one was directly petitioning. Instead, Janus was invoked at the start of every ritual and every prayer. He is to be invoked before any other god, irrespective of their importance to the prayer, ritual, or pantheon as a whole. Jupiter may be King of the Gods and the highest god, but Janus was every beginning and a ritual could not start if it did not begin with praise to Janus.

So even if Janus’s exact importance is not frequently or consciously mentioned after Rome’s religion was hellenized and reflected the Olympian pantheon and structure, the presence of Janus in traditional rituals does show that at some point, his role was vastly different.

Cult Epithets

Due to the formulaic nature of Greco-Roman prayers and rituals, it was often necessary to add in descriptive epithets so as to create additional syllables. This also appears in works of literature where the additional syllables are added to ensure that the line has the right number of beats to it. These descriptors were used to convey something about the deity invoked in a ritual, usually the aspect that the worshipper wished to invoke.

For example, if someone was praying to Venus, they would potentially call upon “Heavenly Venus” or “Venus of Shapely Form.” Poetic epithets were also primarily descriptive in nature; they would possibly refer to “Venus of the Sea Foam” as an immediate reference to the origins of Venus springing out of the sea.

While Janus may not have many attested poetic epithets, there are plenty of older cult epithets that allow the unique position of the two-faced god to be discerned. Some of these are more straightforward to understand than others. Some of the easiest to interpret are titles that either got applied to most divinities or ones that are merely descriptors. An example of the latter is Janus Bifrons or Janus Two-faced/Two-faced Janus. In the Temple of Janus in the forum, he was frequently referred to as Janus Geminus to refer to his dualistic nature. Perhaps the most common of these epithets is Ianuspater or Father Janus.

Pater was an epithet frequently given to male divinities in Rome due to it granting the gods patriarchal authority. Curiously, however, when Janus is referred to as Pater in either literary works or in a religious context, all other male divinities are not to be referred to as Pater. This curious quirk shows the specific importance of labeling Janus as the Father, the highest level of patriarchal authority over the other gods.

The more uncommon cult epithets provide clarity as to why this level of deference was shown to Janus. The Carmen Saliare is a mostly lost piece of text from Archaic Rome centered around religious practices and rituals. It exists only through second-hand accounts, such as the writings of Marcus Terentius Varro. But what fragments there are showcase Archaic Roman religious practices and most importantly, the nature of Janus in Archaic Rome.

One of Janus’s titles that appears in the preserved parts of the opening invocation is that of Janus Rex or Janus King. This fits with Plutarch’s writings indicating that Janus may have been a king or a divine hero in the time of Numa Pompilius. The next major epithet is that of Duonus Cerus, or the “good creator.” Ovid’s writings indicate the tradition of Janus as a creator god and this archaic cult epithet confirms it.

Another epithet is undecided upon by scholars. One interpretation is that it calls Janus “diuum patrem,” or father of the gods, while another interpretation is that it ought to be seen as “diuum partem,” or part of the gods. If the latter is true, then it is of no real importance in determining the function of Janus. But if the first one is true, then Janus’s importance and seniority over all of the other gods is denoted by him once again receiving the crucial title of father. To the Archaic Roman priests who wrote down this invocation, Janus is to be given higher precedence and priority than any other god, showing that he is particularly important and special to their interpretations of the gods.

Perhaps the singularly most curious epithet to appear in the Carmen Saliare as Varro writes it, is “diuum deus” or “god of the gods.” The implications of this epithet are vast.

How Janus May Have Been Used in Archaic Rome

While far from conclusive, there is plenty of evidence from both literary sources in the Late Republic and fragments from Archaic Rome that demonstrate the importance of Janus within Roman religion whether in mythological, literary, or practical terms.

One of Janus’s cult titles mentioned above is that of diuum deus or god of the gods. This incredibly unique title as well as all of the symbolic authority granted to him at the expense of other gods show that at one point in time, Janus was not simply the god of doors. He was the Roman creator god. Janus was every beginning and every ending, his domain, and mastery extending over everything.

This authority and importance is why he was called the father of the gods by the Archaic Romans. Janus had not just created the universe and symbolically created civilization, he had created the gods themselves. His symbolic status as a father to all of the gods that came after creation is what allowed him such deference in hymns and invocations even centuries later.

The gods had divine authority over all of man but Janus had divine and patriarchal authority over the gods. While other gods fulfilled functions that were more specific and concrete, such as the goddess of love or the god of agriculture, to the Archaic Romans, Janus was simply the singularly most important divinity as he was the creator and beginning of all things.

It is important to note that Janus was not some sort of equivalent to a monotheistic god, such as Aten in the Egyptian pantheon. Rather the polytheistic understanding of the world by the Romans allowed Janus to have this level of importance without diminishing the necessity and authority of the other gods. Jupiter was still more important when it came to law and matters of the state, for example.

Janus’s importance was perhaps abstract rather than concrete. It follows then, that as time went on and the incredibly flexible nature of Roman polytheism shifted to adopt new divinities, new philosophies, and new interpretations of the gods, this unique quirk of Archaic Rome likely fell more and more into the background.

Eventually, it would get to the point that some Romans were not quite sure why Janus was invoked at the start of all rituals beyond that being the proper way to practice religion. The importance of Janus remained, but the understanding of the what and why of it all slowly disappeared, leaving him to be something of a curiosity to modern scholars.

Bibliography

Plutarch, Parallel Lives 2.19.5-20.2.

Ovid Fasti 1.

Varro De Lingua Latina 7.26-27.

Bridge, J. 1928. “Janus Custos Belli.” CJ 23:610-614.

Hardie, P. 1991. “The Janus Episode in Ovid’s Fasti.” Materiali e discussioni per l’analisi dei testi classici 26:47-64.

Syme, R. 1979. “Problems About Janus.” AJP 100:188-212.