For centuries, the empires of Rome and China ruled over half the ancient world’s population. Both states had sophisticated governments, commanded large, well-disciplined armies, and held vast expanses of land under their control. Thus, it is not surprising that the enormous wealth and demands of the growing population resulted in the establishment of a lucrative transcontinental trade route — the famous Silk Road.

For hundreds of years, this complex trade network — consisting of land and sea routes — allowed for an unprecedented exchange of goods between the two realms. The goods exchanged included Chinese silk — which was highly prized among the Roman elites, including the imperial family. Yet, the two empires remained only vaguely aware of each other’s existence, with only a few attempts to establish direct contact. Vast distances, inhospitable territory, and most importantly, a powerful and hostile state right in the middle of the Silk Road, prevented the two empires from establishing successful communication, which would have dramatically changed the direction of world history.

Rome and China: The Deadly Banners That Led Rome to the Silk Road

In the early Summer of 53 BCE, Marcus Licinius Crassus, consul-triumvir of Rome and governor of Syria, commanded his legions to cross the Euphrates and enter Parthian territory. Crassus was the wealthiest man in Rome, a man of great influence and power. One thing, however, eluded him — a military triumph. Yet, Crassus would find only humiliation and death in the desert of the East. At the Battle of Carrhae, lethal Parthian horse archers massacred the Roman legions. Their commander fell into captivity, only to be killed. Crassus’ ignoble death would plunge the Roman Republic into a bloody civil war, topple down the old order, and usher in the Imperial era.

Yet, Crassus’ folly offered the Romans their first glimpse of something that would profoundly transform Rome and its society. Before their final attack, the Parthian heavy cavalry suddenly unfurled their gleaming banners, triggering panic among the Roman ranks. What followed was a rout, a massacre, and one of the worst defeats in Roman history. According to historian Florus, brilliantly colored, gold-embroidered banners that so dazzled the exhausted legionaries were Rome’s “first contact” with a gauze-like exotic fabric. It was a dreadful beginning, but silk was soon to be the most coveted item in the Roman Empire and the basis of one of the most famous trade routes in history — the Silk Road. It was the commodity that would link two ancient superpowers — Rome and China.

The Silk Ties Between the Empires

A century before the Roman disaster at Carrhae, another Empire consolidated its power in the Far East. After a decade-long series of campaigns, in 119 BCE the Han dynasty finally defeated the troublesome Xiongnu nomads, the fierce horsemen who prevented its expansion westwards. The secret of China’s success was their powerful cavalry, which relied on the prized “heavenly” horses bred in the Ferghana region (modern-day Uzbekistan). Removing the nomadic threat left China in control of the vital Gansu corridor and the transcontinental route that led West, towards the Ferghana valley, through the Pamir and Hindu-Kush Mountain passes, and beyond, to Persia and the Mediterranean coast. This was the iconic Silk Road.

Meanwhile, Rome was rapidly expanding. The elimination of the last Hellenistic kingdoms left Rome in control of the Eastern Mediterranean and Egypt (and their vast wealth). Decades of civil war were finally over, and the sole ruler of the Roman Empire, Emperor Augustus, presided over a period of unprecedented peace and prosperity. In turn, this boosted the spending power of Rome’s growing population. Both the elites and ordinary citizens went crazy for exotic goods. The Silk Road was the answer. To bypass the Parthian middlemen on the overland Silk Road network, Roman emperors encouraged the establishment of a lucrative maritime route to India. Indian Ocean trade would remain the primary communication avenue between Rome and China until the loss of Roman Egypt in the mid-seventh century CE.

The Enigma of the “Silk People”

By the first century CE, silk was such a highly sought-after commodity among the Roman aristocracy, that the Senate tried and failed to ban men from wearing it. Roman moralists complained bitterly about the revealing nature of fine silks worn by Roman women. Pliny the Elder disapproved of the scale and value of this trade in eastern luxuries, blaming it for draining Rome’s coffers.

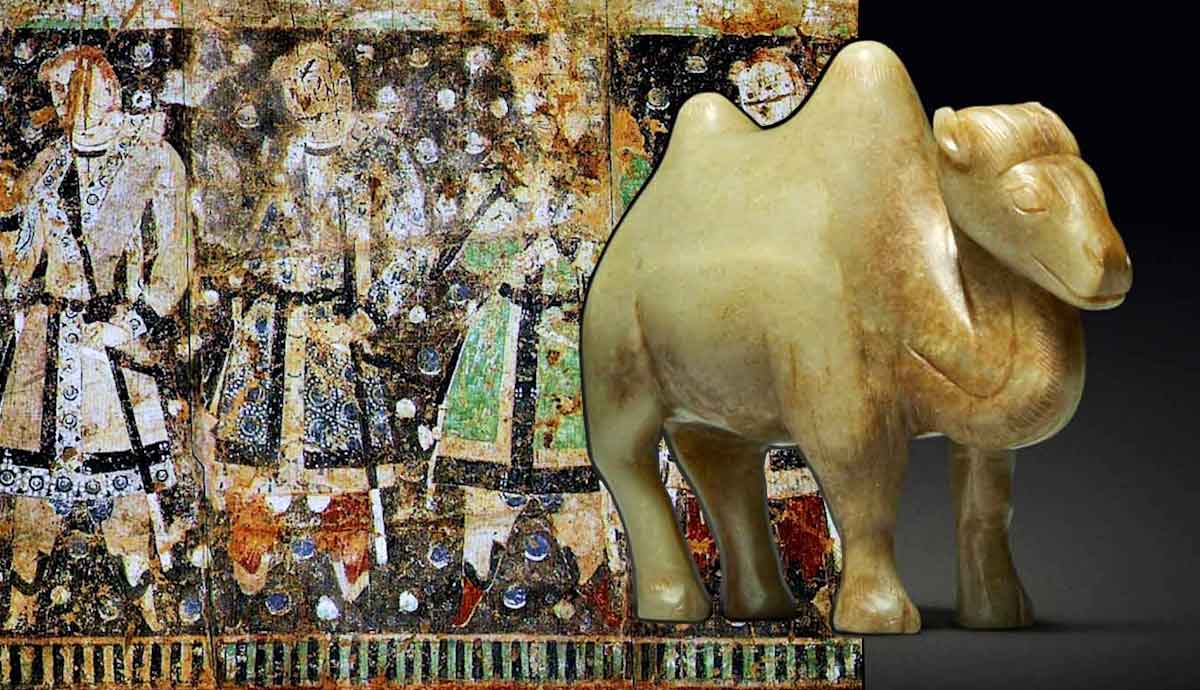

Despite the increase in Silk Road trade, the vast distances, inhospitable landscapes, and the hostile state right in the middle of the route — the Parthian Empire — presented an obstacle to establishing closer connections. In addition, trade was indirect. Instead, the people of Central Asia — most notably the Sogdians, as well as the Parthians, and merchants from the Roman client states of Palmyra and Petra — acted as the middlemen. Thus, although goods constantly traveled between Rome and China, the empires remained only vaguely aware of each other’s existence.

Most of Roman knowledge about China came from rumors gathered about distant trade ventures. According to the Romans, the Seres — “Silk People” — harvested silk (sericum) from forests in a remote territory on the other edge of Asia. However, the identity of the Seres is unclear. While the Roman historian Florus describes a visit of numerous embassies, including the Seres, to the court of Emperor Augustus, no such account exists on the Chinese side. Could the Seres be one of the central Asian peoples who acted as intermediaries, trafficking exotic goods along the Silk Road?

The Failed Expedition

In the mid-first century CE, under the command of general Ban Chao, Han forces invaded the Tarim kingdoms south of Ferghana, bringing the oases of the Taklamakan desert, a vital part of the Silk Road, under imperial control. More importantly, by taking control of the region, the Chinese army reached the north-eastern border of an old Roman enemy — Parthia. By then, the Chinese were aware of Rome’s existence, probably due to questioning the merchants traveling along the Silk Road. According to Han reports, the Roman Empire — known to the Chinese as “Da Qin” (Great China), was a state of considerable power. In 97 CE, Bao Chan dispatched an ambassador named Gan Ying to discover more about the far-flung western realm.

The Parthian Empire feared direct contact between Rome and China and a possible alliance. The concern was justified, as the Gan Ying embassy’s task was to break the Parthian monopoly on the Silk Road. Thus, the Chinese embassy traveled covertly across the Parthian territory, reaching the Persian Gulf. From there, it would have been possible to follow the Euphrates north to the Roman border in Syria in a few weeks. However, Chinese reports indicated that Rome lay northwest of the Indian Ocean, so Gan Ying planned to sail around Arabia to Roman Egypt, a journey of three months. Yet, the Han envoy never reached the emperor’s court. Discouraged by the local sailors’ stories of bad weather and terrible sailing conditions to Egypt, and unwilling to pay more than initially agreed upon, Gan Ying abandoned his mission. However, the envoy brought back more details about the countries to the west of China, including more information about the Roman Empire.

The Unexpected Arrival in China

Several years after the failed Chinese mission, in 116 CE, Emperor Trajan brought his legions to the shore of the Persian Gulf. By that time, however, the Chinese had already retreated, as their control over Tarim territories disintegrated. Within a year, Trajan was dead, and his successor Hadrian withdrew the army from Mesopotamia, consolidating the Empire’s frontier. Yet, the Roman interest in the Far East continued, with Roman explorers traveling to China using the Silk Road. According to geographer Ptolemy, in the early second century, a group of Romans traveled to Seres (“the land of silk”), reaching the “great city of Serica.” Could this be Han capital Luoyang? Chinese accounts also report the arrival of foreign representatives search for by Ban Chao in 100 BCE. If those were the same Romans, then the expedition of Gan Ying was not in vain.

The breakthrough in the Sino-Roman relationship occurred in the mid-second century. Since the establishment of the Indian Ocean trade route, the impassable barrier of the Malay peninsula blocked the progress of Roman ships further east. In addition, adhering to sailing timetables directed by seasonal winds limited exploration east from the Bay of Bengal. The Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, and Ptolemy’s Geography, written in the first and second centuries, respectively, mention the people of Thinae or Sinae, who lived in the far-flung “silk land,” east of the Malay.

Finally, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, in 166 CE, a Roman ship managed to sail around the peninsula and reach the port of Cattigara. This was probably the ancient town of Oc Eo in south Vietnam. From there, Han soldiers escorted the Romans to the imperial court. Were they traders acting in their own interest or official envoys of the Roman emperor? It is hard to say. The Han, however, did not doubt that the representatives were legitimate. After all, traders carried the protection of Rome on their travels and could represent the interests of the Roman state in the distant kingdom. After more than a century of using intermediaries for the Silk Road trade, the two empires had a conduit for direct communication.

The Silk Road was more than just a trade route. It was also an avenue for exchanging people and ideas. Unfortunately, the well-developed route network could also be exploited by more dangerous, invisible “stowaways.” When the Roman envoys returned with the news of diplomatic contacts with China, they found their home decimated by smallpox. The deadly pandemic struck both empires, finding easy prey in overcrowded towns, leading to a loss of a tenth to a third of the population. Moreover, the pestilence weakened their defenses, allowing barbarian invaders to advance deep into the imperial heartland. Yet, China and Rome recovered, reasserting control and retaining dominance in their respective parts of the world during the following century.

Rome and China: The Perils of the Silk Road

Rome’s interest in the Far East, however, was fleeting. The emergence of the mighty and hostile Sassanid Empire in the fourth century CE and increased military expenditure diminished Silk Road trade on land and sea. The Roman West’s subsequent collapse further magnified the importance of the Eastern frontier. The new imperial capital and a major trade hub — Constantinople — became the center of the rejuvenated Roman Empire, which under emperor Justinian, managed to restore supremacy over the Mediterranean.

Incidentally, Justinian’s reign marked the historical moment when the Romans secured their own silk production source after two monks smuggled silkworm eggs to Constantinople. A few years later, in 541 CE, a horrific plague struck the Empire, decimating its population, ravaging the economy, and bringing dreams of reconquest to an end. Using the Silk Road network, the plague traveled rapidly eastwards, passing through Sassanid Persia, and striking China.

Then, in the mid-seventh century, the Eastern frontier exploded. The Roman and Persian armies went into a war of annihilation. Dubbed the “Last War of Antiquity,” a long and bloody struggle, fueled by opposing religions and ideologies, ruined both Empires, and left them easy targets for the armies of Islam. Unlike Persia, the badly wounded Roman Empire survived the onslaught but lost its wealthy eastern provinces to the armies of Islam. The Caliphate was now in control of the Silk Road and could do what Rome failed to do, reaching the border of Tang China. The Arabs ushered in a new Golden Age along the Silk Road, but that is another story.