Russian Civil War propaganda had a bold and convincing style. Posters adorned urban sites, while trains draped in patriotic colors steamed through the countryside. Propaganda media brought land, peace, and liberation themes that appealed to an often illiterate, multi-ethnic population. Designed for busy urbanites or those who could not read, visual media offered the most direct way to change popular opinion. Bolshevik and White Army propaganda machines developed effective techniques for their target audiences.

Here is how Russia’s information war worked to change the political landscape 100 years ago.

A Nation Ripe for Change

In the winter of 1917, facing desertions, bread riots, and a population weary from the First World War, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the Russian throne during the February Revolution. A provisional government replaced Russia’s monarchist regime. Intended as an interim governing body, the Provisional Government filled the gap until a constituent assembly could elect representatives for a new, democratic Russia.

A summer of unrest, violence, and bloodshed ensued. The Eastern Front hemorrhaged with widespread desertions. Soldiers, sailors, and agitators roamed streets with weapons and revolutionary banners. Soldiers’ soviets or councils sprang up across the country. Most people wanted to have a say in who ruled them. The Constituent Assembly, an elective representative body, planned to meet to enable citizens to determine their new form of government.

The Provisional Government’s vow to continue the war made it unpopular. During the July Days uprising, the government failed to crush the Bolshevik Party. This move helped the Soviets position themselves for a political takeover several months later.

A Military Coup

On October 25, 1917, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, seized control of the Provisional Government. In the aftermath, the Bolsheviks worked hard to portray the coup in the media as a popular uprising.

During the next two months, the Bolshevik Party, named for the word “majority” (bol’shinstvo), made every effort to consolidate power. Although they represented a political minority, the Bolsheviks seized urban centers and factories. They also promoted their agenda with popular slogans like “Bread, Peace, and Land.” Propaganda proved a powerful way to tap into the nation’s war-weariness and land hunger to foment class war in Russia.

A Dissolved Electoral Process

After the October Revolution, many people still believed that the Constituent Assembly would determine the next government in Russia. But events took an unexpected turn.

On January 5, 1918, the Constituent Assembly met for a 13-hour session in the Tauraide Palace in Petrograd. They aimed to form a new, elective government and draft a constitution for postrevolutionary Russia.

The first free elections in Russia in November 1917 proved a bitter disappointment for the Bolsheviks. While the party held a majority among soldiers and sailors, they only gained 25% of the national vote. This result failed to support the Bolsheviks’ claims as a majority party and their assertion that the October Revolution represented a popular uprising that legitimized Soviet power. While revolutionary protests raged outside, Lenin argued that the Bolsheviks and Social Revolutionaries split the peasant vote. The Bolsheviks then denounced the Constituent Assembly and dissolved it on the spot. This action ushered in a single-party political system.

On March 3, 1918, the Soviets signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers, a separate peace that ended Russia’s participation in World War I.

Some people refused to accept the Constituent Assembly’s dismissal, the loss of a liberal constitution, and the Bolshevik seizure of power. Officers who fought in the First World War saw the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as a betrayal of the country’s sacrifices and their commitment to the Allies. Since the Soviets occupied Moscow and Petrograd, the anti-Bolsheviks fled south to the borderlands to form a Volunteer Army.

Two Sides Emerge

In response to rising terror and the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, counterrevolutionary forces gathered in southern Russia and eastern Ukraine. The Volunteer Army first emerged under General Mikhail Alekseev and later as the Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR) under Baron General Pyotr Wrangel. The anti-Bolshevik armies represented a loose confederation of resistance movements in North Russia, Siberia, the Caucasus, and Ukraine.

In contrast to Soviet propaganda, most White officers and soldiers did not come from blueblood backgrounds; many came from unprivileged commoner classes. Their ranks spanned a wide range of political views, including monarchists, liberal Kadet Party members, democratic-republicans, Kuban Cossack separatists, and those motivated by ideas of a free Russia rather than a particular political ideology. Unlike the Soviets, the anti-Soviets did not share a single political goal. A gray space existed between these opposing forces, including Greens, partisans, anarchists, social revolutionaries, and Ukrainian nationalists.

Meanwhile, Leon Trotsky, the Bolshevik war commissar, whipped Red Army recruits into shape to fight the better-trained but smaller White forces.

For several years, a bitter and complex war raged across Russia. By November 1920, the Red Army pushed the Armed Forces of South Russia back to Crimea and forced a mass evacuation of soldiers and civilians fleeing advancing Soviet forces. In Siberia, the Caucasus, and Ukraine, anti-Soviet military activity continued into the 1920s.

Russian Civil War Propaganda: Origins & Goals

Propaganda posters first appeared in Russia during the First World War. Visual media plastered across shops, fences, and railway stations demonized the Germans and Austrians and helped boost war morale. The political shift during the Russian Civil War meant that opposing forces adapted the propaganda medium for new, recognizable uses.

Bolshevik and anti-Bolshevik propaganda had a similar goal: to convince people to support their cause and prevent the other side from consolidating power. The Soviets promised to solve concrete issues such as bread, peace, and land. While the anti-Soviets grasped the importance of major political and economic issues like nationalism and land distribution, they did not think they had the right to make these promises. Instead, the Whites focused on providing clear information about the Soviets’ intentions and actions. They worked to oust the Bolsheviks and pave the way for peacetime elections to choose the new form of government.

War Communism represented a different reality from the utopia of Soviet propaganda posters. Due to the war’s destruction, historic weather conditions, disruption of the agricultural process, grain confiscations, and nationalization of resources, famine became more common than bread. While the Soviets ended Russia’s participation in World War I and gave soldiers the peace that they demanded, the Bolshevik seizure of power sparked a new war with tragic consequences for millions of people across the former Russian empire.

Forces Behind Russia’s Propaganda War

Soviet propaganda posters, films, and agitation trains ensured that people knew who was to blame: officers, landowners, priests, bourgeoisie, kulaks (peasant landowners), and Western capitalists. On the other side, anti-Soviet propaganda blamed one enemy for the country’s chaos: the Bolsheviks themselves.

While Soviet propaganda aimed to entice the masses, the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission, abbreviated as VChK or the Cheka and headed by Felix Dzerzhinsky, established control through a policy of terror. An implicit part of Leninist theory, terror played a preemptive role in hunting out and eliminating suspected enemies of the state.

The Cheka profiled possible enemies based on an endlessly changing list of possible crimes. Propaganda helped the secret police and citizen informers identify and punish various potential counterrevolutionaries.

At the height of the Red Terror in 1919, the Red Army and the Cheka launched a sustained campaign of extrajudicial terror against millions of people to eliminate specific classes or ethnic groups.

Red & White Propaganda Machines

From the outset, the Soviets grasped the media’s importance in the fight to extend socialist power. They wielded every tool to leverage the media to their advantage.

Since the Bolsheviks held the factories and urban centers near Moscow and Petrograd, the anti-Bolsheviks gathered in border cities and rural frontiers. White printing and artistic resources remained scarce, while the Soviets retained a wealth of professional revolutionary artists, including Vladimir Mayakovsky, Boris Kustodiev, El Lissitzky, and Dmitri Stakhievich Moor.

Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) artists combined constructivism and avant-garde styles to promote Soviet messages. These art styles, inspired by industry and characterized by geometric forms, heralded a fundamental social shift from an agricultural to an industrial society.

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) created numerous chromolithograph posters that drew on historical themes, fantasy, and early twentieth-century Russian folk art.

The sheer scale of Soviet propaganda efforts is staggering. Spreading political messages to the masses required mass harnessing of state financial and logistical resources. Between 1918 and 1920, Soviet propaganda trains showed 1,008 presentations to 2,752,000 people. Over 1,740 propaganda offices and organizations operated in urban areas. Soviet print shops churned out three million newspapers, posters, and leaflets and held 753 agitation meetings with over one million attendees in 1919 alone.

ROSTA and VTsIK leveraged state resources to spend 11 million rubles on information and disinformation, making propaganda films available to millions in one year.

Meanwhile, the White propaganda machine OSVAG, Azbuka intelligence services, and other organizations such as the National Centre, the State Unity Council of Russia, and the Union for the Regeneration of Russia churned out posters, leaflets, and pamphlets that helped neutralize the impact of Soviet propaganda. Unlike the Bolsheviks, the Whites did not completely control the flow of information in the regions held by their armies (Lazarski 1992, p. 695).

In September 1918, six months after the civil war began, General Alekseev founded a civilian propaganda organization known as OSVAG. This department replaced the previous Military-Political Department propaganda machine.

While most OSVAG and Azbuka propagandists did not have formal art or agitation training, they included many politicians, journalists, and intelligence officers. A few months after the war started, Azbuka aimed its agitation efforts at recruiting soldiers to the White cause while providing vital information to the public (Lazarski 1992, pp. 695-696, 702).

The mobile nature of the war created problems for OSVAG and other White propaganda organizations. Corruption and in-fighting added additional barriers to effective propaganda. The Volunteer Army stayed on the move, fighting or evading larger forces, trying to feed its soldiers, and trying to raise support. Once the Volunteer Army established its base in the northern Caucasus, they redoubled their propaganda efforts.

By 1919, the White propaganda budget rose to 68 million rubles. While this number highlighted the importance the anti-Soviets placed on propaganda efforts, this budget shrank due to rampant inflation. White amateur propaganda artists also received little pay and worked under demanding conditions, battling shortages, typhus epidemics, and frequent capture and execution by the Bolsheviks.

Despite technical issues and paper shortages that hampered the White media war, thousands of books, posters, pamphlets, and leaflets rolled off their presses. While stationed in Kyiv, OSVAG produced hundreds of copies per day. They printed four million posters, 1.5 million leaflets, pamphlets, and over 300 books in just three months. The Whites made their print and visual media available to the public via a network of small mobile libraries. Like the Soviets, they also pasted posters in urban window exhibits or tacked them up in rural villages (Lazarski 1992, pp. 702-703).

At first, OSVAG operated within areas controlled by the anti-Soviet armies. While they developed social reform programs and attempted to disseminate propaganda throughout Russia, they needed more resources and support to realize their goals.

Russian Civil War Propaganda in Action

The Bolsheviks and anti-Bolsheviks employed a variety of propaganda media to target a population with a 40% average literacy rate.

Agitprop trains (agitpoezda), called ”Lenin Trains” or “Trotsky’s Train,” toured the countryside in 1918. They featured colorful posters, satirical images splashed across train cars, journalists, actors ready to perform plays, and a cinema room.

Agit-trains contained a printing press, enabling the Soviets to print and toss posters out the window as they steamed past villages. At every stop, crowds of peasants and workers took a break from their daily lives to enter a cinema car and take in dramatic scenes from propaganda films. Windup gramophones played Lenin’s recorded speeches to waiting crowds. Steamers like Red Star and Red East also toured Russia’s abundant inland rivers like the Volga to bring revolutionary propaganda to the people.

When it came to colorful, abundant, and relentless propaganda, even anti-Soviet leaders admitted that the Bolsheviks won the propaganda war.

Like the Soviets, the Whites held lectures, played films, and handed out propaganda material to the people. In contrast, they experienced paper shortages, a lack of trains, fewer professional artists, and logistical issues with inflation, production, and distribution.

Despite financial and practical limitations, the Volunteer Army recognized the power of words and worked to educate and engage the masses. White propaganda trains covered with slogans called for people to unite and fight Soviet power. White agit-trains also brought Red Cross cars filled with food and medical supplies. The Volunteer Army developed a staff of propagandists who handed out posters and leaflets promising a brighter future for those who joined them.

In the spring of 1919, six anti-Soviet propaganda trains, covered with flowers and plastered with slogans such as “Eight-Hour Working Day,” “Land for the Toiling Masses,” and “Let Us Be One Russian People,” rolled into liberated areas. These messages focused on land issues, workers’ rights, and political divisions that concerned ordinary people.

The Whites outfitted each propaganda train with an electric generator to power a printing press that printed posters, newspapers, and leaflets. Their trains also featured a store that carried items, such as cigarettes, that many people found difficult to get during the war. Other cars contained a library with a reading room and a restaurant. By late 1919, the Whites had access to four agitation trains to help spread propaganda to areas accessible by railway lines (Lazarski 1992, p. 705).

Like the Soviets, the Whites recognized the visual power of propaganda films. In Kharkiv, Ukraine, they employed three mobile moving picture theaters and several theater buildings. They poured money into film production efforts, including promotional films and documentary footage of Bolshevik atrocities (Lazarski 1992, p. 700).

While propaganda alone could not restore law and order in Russia, the Whites fulfilled their goals by providing information, raising support, and effectively counteracting Bolshevik propaganda in the regions held by their forces.

Differences Between Red & White Propaganda

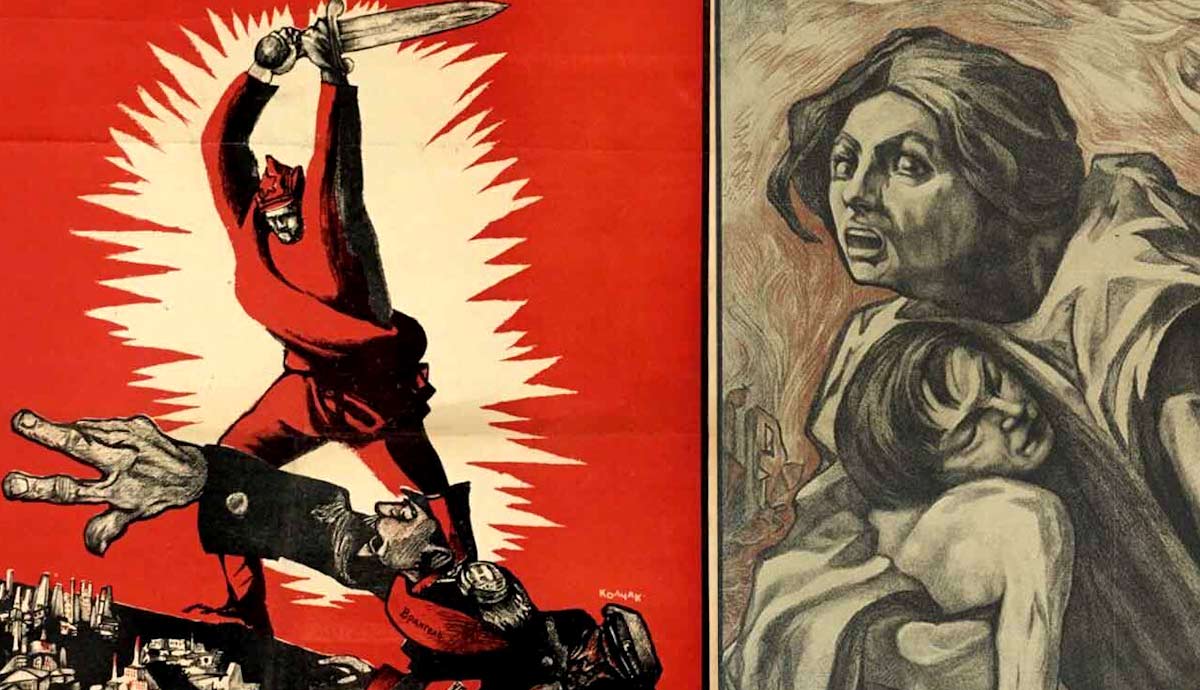

Soviet posters typically demanded action. Anti-Soviet posters often begged for help.

The Soviet propaganda machine produced a firehose of propaganda materials that promoted labor, education, class warfare, and support for their forces at the front. This is because the Soviets wanted to rally the population behind them and promise a better future after they wiped out their enemies. White propaganda remained rooted in the horrors of the present, although they also produced media that envisioned ultimate victory.

Bright and glossy Soviet posters included eye-catching folk art styles intended to appeal to busy workers and peasants. OSVAG often used stark, monochromatic designs and muted colors, although they occasionally relied on bold and colorful media.

In urban areas, ROSTA developed propaganda sheets for public display. They used constructivist images and simple phrases that encouraged people to fulfill a variety of Soviet decrees. These geometric ROSTA posters became known as “windows of satire” because they first appeared in empty shop windows along Kuznetsky Most Street in Moscow. Thus, the contrast between idealized Soviet culture and the lack of food evolved into dark political satire.

In addition to stylistic differences, Soviet and anti-Soviet propaganda relied on different themes. Bolshevik propaganda showed the Red Army triumphant and larger than life. They depicted their enemies as parasites, idlers, capitalists, and bread-burners rather than liberators.

Anti-Bolshevik propaganda focused on waging a holy war against Bolshevik crimes (Lazarski 1992, p. 700). Their propaganda images included home, religion, defense, and apocalypse themes. They relied less on color and more on a shock effect that showed War Communism’s practical results. They believed that revealing the Red Terror’s grim realities would prove enough to sway support from the Soviets.

Waging an Information War

During the Russian Civil War, visual media played a crucial role in bringing ideas to the masses at a time when many people could not read or write. The Whites and the Reds understood that imagery had an immediate and emotional power that a thousand words could not convey.

Propaganda proved an effective way to distract from social and economic problems, unite an audience, and secure support by othering the enemy. White propaganda typically portrayed negative aspects of Bolshevik power. Their posters often showed ordinary people suffering from War Communism. In contrast, Soviet propaganda showed the people rising victorious from under the feet of their capitalist overlords. Each used visual media in posters and films to spread information and disinformation. This balance between reality, caricature, and idealism played a significant role in waging an effective information war.

In the visual information war, Bolshevik propaganda dehumanized the enemy, legitimized political terror, promoted literacy, and gathered support to win the civil war. The Whites struggled to counterbalance the deluge of Soviet propaganda and experienced issues with resources and unity. They also developed a robust propaganda machine that focused on providing information about human rights violations.

Outside the Soviet Union, the anti-Soviets continued their propaganda war for a free Russia. The Soviets focused on restructuring the economy and society through collective agriculture, labor, education, and industry. They continued to employ various propaganda techniques to eliminate class enemies and promote the rise of the USSR.

Suggested Further Reading

Christopher Lazarski, ”White Propaganda Efforts in the South during the Russian Civil War,” The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 70, no. 4 (October 1992).