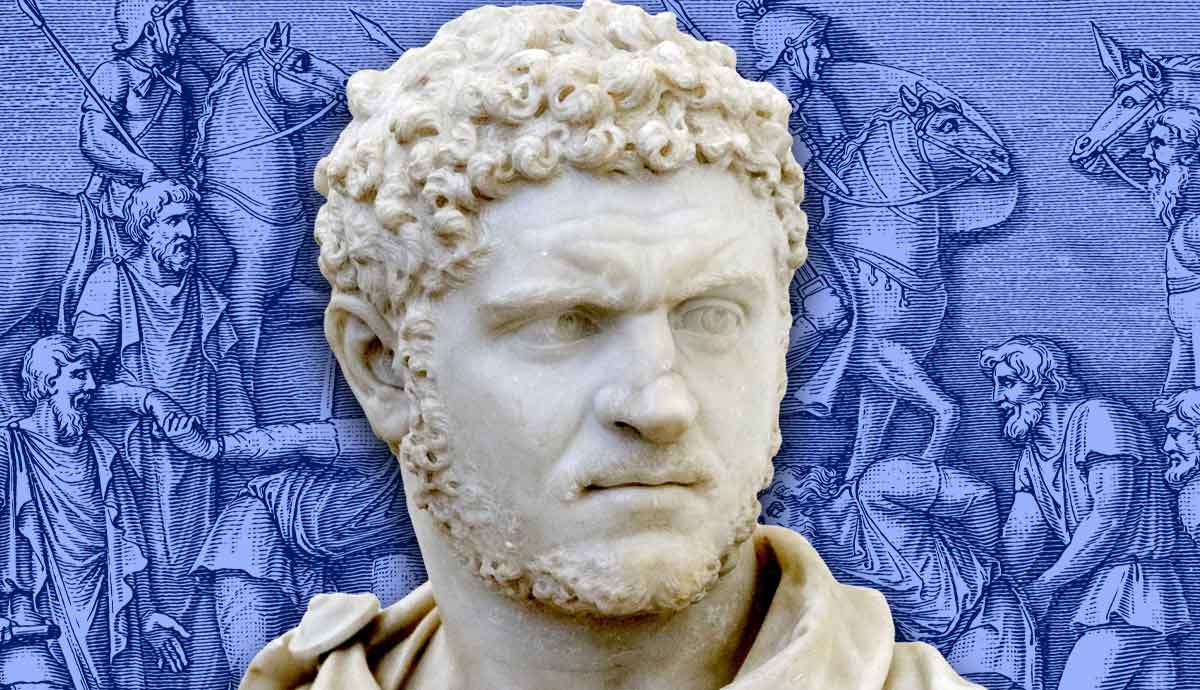

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, better known as Caracalla, was a Roman emperor who ruled from 198 to 217 CE. Caracalla was the elder son of Emperor Septimius Severus, the founder of the Severan dynasty. “Caracalla,” was his nickname, derived from the Gallic hooded tunic, popular among soldiers on the Rhenian limes. As the first “soldier emperor,” Caracalla spent more time in military camps than in the imperial capital.

He continued his father’s policy of favoring the military, which earned him the scorn of the senatorial elite. Caracalla presided over several military victories and commissioned the construction of the colossal Baths of Caracalla in Rome. His most significant act, however, was granting Roman citizenship to all free men in the Empire through the Edict of Caracalla. Despite these accomplishments, he is often remembered for his ruthlessness, particularly the infamous murder of his younger brother Geta. Caracalla’s assassination in 217 CE marked the end of his rule, though the Severan dynasty continued after his death. And his style of rule became a trend during the third and fourth centuries.

Caracalla Was a Member of the Severan Dynasty

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, better known as Caracalla, was born in 188 CE to Roman general and politician Septimius Severus and Julia Domna. His early years were marked by chaos, as his father seized control of the Roman Empire, following the tumultuous “Year of the Five Emperors.” In 198 CE, the 10-year-old Caracalla became co-emperor, along his father. In 209, Caracalla’s younger brother Geta was also granted a title of Augustus.

After Septimius Severus’ death in 211 CE, both brothers inherited the throne, with Caracalla as the senior and Geta as the junior emperor. The co-emperorship, however, was fraught with tension and rivalry. Childhood competition and personal dislike was exacerbated by differing views on political strategy. It did not help that both emperors were influenced by their advisors, powerful individuals, and factions at court, who sought to exploit the conflict between the two for their own personal gains.

He Murdered His Brother

While imperial propaganda propagated the image of a happy family, the conflict between two brothers simmered. Despite efforts of their mother – empress Julia Domna – to reconcile her sons, the relationship between the co-emperors deteriorated further. Finally, in December 211 CE, the tension reached a deadly climax. Caracalla convinced his mother to arrange a peace meeting in her apartments, thereby depriving Geta of his bodyguards. During the meeting, Caracalla’s men attacked and murdered Geta, who died in his mother’s arms.

This act of fratricide shocked Rome, leaving Caracalla as the sole emperor. He ordered a damnatio memoriae, erasing Geta’s image and name from all public monuments and records. A purge followed, with Geta’s supporters arrested or executed. Infamously, Caracalla slaughtered the ruling elite of Alexandria, allowing his troops to plunder and ravage town. While this is clear evidence of Caracalla’s brutality, it is possible that he reacted preemptively to prevent a planned rebellion in Alexandria, where the ruling elites had supported Geta. By resorting to such drastic measures, Caracalla made it clear what would happen to anyone who opposed him.

Caracalla Was a Soldier Emperor

Perhaps to distance himself from the accusations of fratricide, Caracalla left Rome in 213 CE, never to return. For the remainder of his reign, Caracalla lived in the military camps, travelling along the imperial limes. Here, in the company of his soldiers, the emperor followed his father’s deathbed advice: “Enrich the soldiers and forget everyone else.” Caracalla raised legionaries’s pay, and bestowed generous donatives upon them. The emperor adopted the lifestyle and attire of the common soldier, wearing the Gallic cloak – the caracallus –which gave him the nickname.

Emperor Caracalla, who in his youth followed his father on campaigns in Parthia and Britannia, presided over several military victories, most notably over the Alamanni on the Rhine, for which he was awarded the title of Germanicus Maximus. Caracalla’s down-the-earth approach, and willingness to share in military hardships, endeared him to his legions. However, his patronage of the soldiers, although beneficial for boosting morale, placed a significant strain on the Empire’s finances.

He Left a Lasting Trace on Rome

To help manage the growing military expenditures, Caracalla introduced the antoninianus, a new silver coin, although this led to inflation. Needing more money, the emperor found an ingenious solution. In 212 CE, he famously issued the Constitutio Antoniniana, or the Edict of Caracalla. Caracalla’s Edict granted Roman citizenship to all free men in the Roman Empire, irrespective of their social standing, ethnicity or profession. As historian Anthony Kaldellis stated, “The Empire became the world.” The edict had a practical side as well, greatly increasing the taxpayer base and bringing much-needed funds into the imperial treasury.

The influx of money allowed Caracalla to embark on major infrastructure projects. The Baths of Caracalla (Thermae Antoninianae), commissioned in 212 CE, still stand as a testament to the emperor’s ambition. This monumental bath complex in the heart of Rome featured advanced engineering, including an intricate heating system, and acted as a social hub for all free Roman citizens. Lavishly decorated, with splendid mosaic, vivid frescoes, and some of the most beautiful statues of antiquity, the thermae would inspire engineers, artists, and architects from the Renaissance to the present day.

Emperor Caracalla Was Assassinated

Despite his attempts to please the army, Caracalla’s ruthlessness caused discontent among some of his officials, who waited for an opportunity to strike. The opportunity finally presented itself, when Caracalla embarked on the Parthian campaign in 217 CE. Like many Roman leaders since Crassus, Caracalla was lured by the prospect of the military glory in the East. By conducting a campaign, the emperor also hoped to emulate his idol – Alexander the Great. Additionally, a triumph against Parthia would help improve Caracalla’s reputation, which had been tarnished by fratricide. It was not to be.

While en route to Carrhae, Caracalla stopped at the side of the road to relieve himself. Seizing the opportunity, a soldier named Julius Martialis approached and drove a dagger into the emperor’s back. Mid-stream, half-dressed and unaware, it was an ignoble end for a soldier emperor. The Severan line was preserved by the new emperor, Caracalla’s praetorian prefect Macrinus, who took the name “Severus,” but the dynasty was living on borrowed time, finally ending in 235.

Caracalla was right in recognizing the soldiers as powerful backers, but only for Roman emperors who proved to be competent commanders. And after Caracalla, no Severan ruler could maintain the loyalty of the soldiers for long. Caracalla’s focus on the military and his role as a soldier-emperor were harshly criticized by contemporary sources, but this approach would become a trend in the tumultuous third century.