![]()

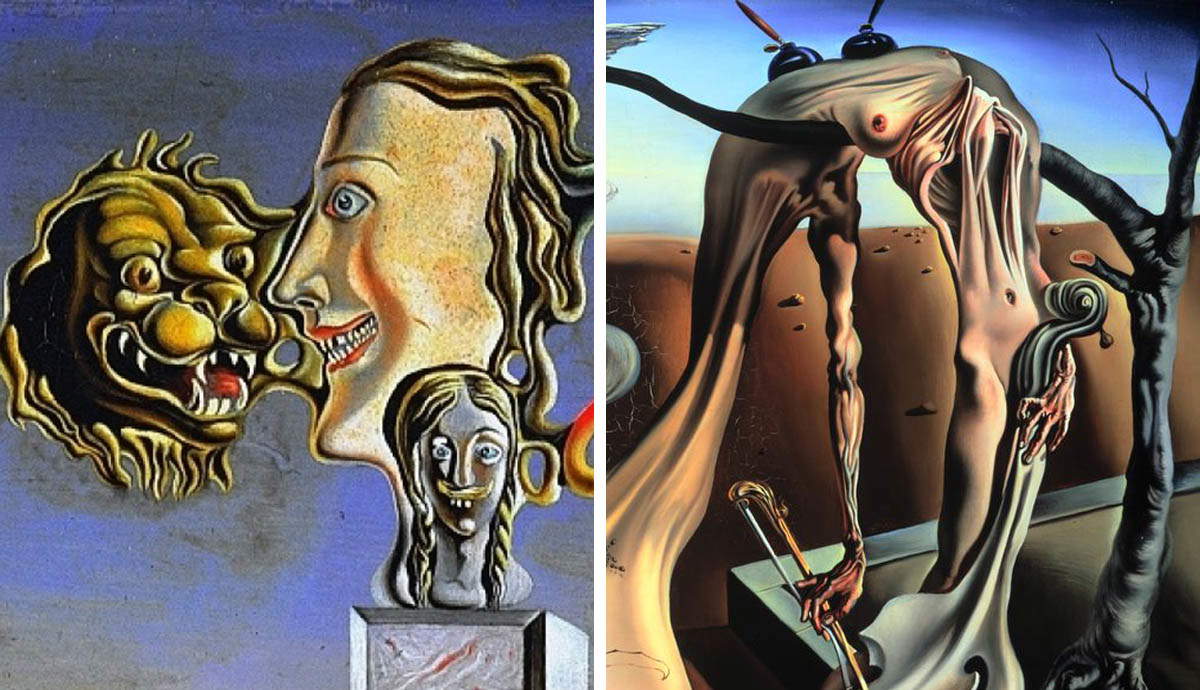

Salvador Dali is internationally renowned as the flamboyant face of Spanish Surrealism. A master of self-promotion, his character was as colorful and eccentric as his art. His career expanded over six decades and encompassed an extraordinary range of media from painting, sculpture, film, and photography to fashion design and graphics. He was fascinated with the uncharted depths of the unconscious human mind, dreaming up mystical, imaginary motifs, and barren, desolate landscapes.

Salvador Dali: Life in Catalonia

Born Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dali I Domenech in 1904 in Figueres, Catalonia, Dali’s parents led him to believe he was the reincarnation of his older brother, who had died just 9 months before he was born. A tempestuous and unpredictable child, Dali was prone to outbursts of rage with family and friends, but he showed an early aptitude for art which his parents were keen to encourage. His artistic eye was particularly drawn to the Catalan countryside, which would continue to influence his art as an adult. While still a teenager, Dali entered the Madrid School of Fine Arts, but his mother sadly died a year later when he was only 16, an experience that left him utterly heartbroken.

A Rebel in Madrid

As an art student at the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid, Dali developed his signature, dandy style of dress, with long hair and knee-length britches. He also read Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, 1899; its analysis of the subconscious human mind had a profound influence on Dali’s career. At art school, Dali was a rebellious student who had already once been expelled from art school for leading a student protest, while in 1925 he refused to sit his art history oral exam, so he never officially completed his degree, claiming, “I am infinitely more intelligent than these three professors, and I, therefore, refuse to be examined by them. I know this subject much too well.”

Parisian Surrealism

In 1926 Dali traveled to Paris, making what would become a life-changing trip. Visiting Picasso’s studio and witnessing work by the Cubists, Futurists, and Surrealists profoundly affected his way of thinking about art. Returning to Spain, Dali made paintings that moved beyond reality into metaphysical realms, with symbolic motifs in dreamy landscapes, including Apparatus and Hand, 1927, and Honey is Sweeter than Blood, 1927. Just one year later, Dali created the radical film Un Chien Andalou, 1928, with filmmaker Luis Bunuel. Its violent graphic and sexual imagery caused ripples of shock and amazement among the Parisian Surrealists, who invited him to come to Paris and join their cause.

Unconventional Methods

Dali claimed a range of unusual techniques helped him find inspiration for his surreal motifs. One involved falling asleep while holding a tin plate and a spoon; the noise of the spoon falling onto the plate would wake him just in time for him to remember his dream. Another was standing on his head until he almost fainted, inducing a semi-lucid state which came to influence famous works such as The Persistence of Memory, 1931, made when he was just 27. Dali also developed his “paranoiac-critical,” style, where a sense of unease was conveyed in his works through optical illusions, strange multiplications, and distorted body parts or bones which symbolized subconscious Freudian meanings; his Metamorphosis of Narcissus, 1937, is a classic example.

Life as an Outcast

Dali often articulated opinions aimed at causing provocation. When he expressed a strange infatuation with Adolf Hitler, Andre Breton, the far-left leader of the Surrealist group, quickly expelled him from society. Further scandal was caused when Dali began a relationship with Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, known as Gala, while she was still married to his friend, the Surrealist poet Paul Eluard – she soon left Eluard for Dali, and the pair married in 1934. The disgrace left Dali shunned by his father and their entire hometown in Catalonia, but he sought a spell of refuge in an exiled shack in the Spanish fishing village of Port Lligat. Towards the end of the decade, Dali found new contacts in the world of commercial design, famously working with fashion couturier Elsa Schiaparelli and the designer and arts patron Edward James, who commissioned Dali to create the Mae West Lips Sofa in 1938.

The United States and Popular Culture

In the late 1940s, Dali moved to the United States with Gala, living between New York and California, where he hosted lavish, decadent parties. Working between the fields of fine art and design, he was endlessly prolific, collaborating with others to produce fashion, furniture, graphics, and theater sets; one of his most well-known motifs is the Chupa Chups logo which is still in use today. Dali also dabbled in acting, appearing in a number of television adverts, although such blatant money-making schemes only alienated him further from the French Surrealists.

Later Years

Gala and Dali returned to Figueras in 1948, spending time in New York or Paris in the colder winter months. In Figueras, Dali developed a new style called “Nuclear Mysticism”, fusing Renaissance and Mannerist Catholic imagery with supernatural or scientific phenomena; figures were painted at sharply foreshortened angles, positioned among rigid, geometric forms and haunting, stark lighting. In 1974 he completed the ambitious Dali Theater-Museum in Figueres, which remains one of his greatest legacies; after his death in 1989, he was buried in a crypt below the museum’s stage.

Legacy

Dali’s flamboyant, ostentatious life and work have made him a much revered, iconic figure in the history of art. Since his death, auction prices have remained consistently high, including Nude on the Plaine of Rosas, sold for $4 million, Night Spectre on the Beach, for $5.68 million, Enigmatic Elements in a Landscape, 1934, at $11 million and study for Honey is Sweeter than Blood, selling for $6.8 million. Printemps Necrophilique, 1936, recently sold for even more, reaching $16.3 million, while Portrait de Paul Eluard, 1929, hit a staggering $22.4 million at auction, making it the most valuable of Dali’s canvases and the most expensive Surrealist artwork ever sold.

Did you know this about Salvador Dali?

Dali had a crippling phobia of grasshoppers as a child and school bullies would throw them at him to torment him. As an adult, grasshoppers and similar motifs often appeared in his artwork as symbols of decay and death.

Throughout his career, Dali became notorious for his provocative stunts. In one incident, he appeared at an International Surrealist exhibition in full diving gear, claiming he was “diving into the human subconscious”. After trying to deliver a lecture in the old diving suit, he nearly suffocated, before being rescued by a friend.

Dali had a curious fascination with cauliflowers, once arriving to deliver a speech in a Rolls Royce full of them.

The nickname “Avida Dollars” was attached to Dali by the art community, an amalgam of his name and a nod toward his commercial ventures.

Dali had a penchant for unusual pets; he adopted an ocelot in the 1960s who he named Babou and took almost everywhere with him. He also had a pet anteater, who he would take for walks in Paris.

“It’s the most serious part of my personality…”

Dali’s iconic, comically upturned mustache was initially influenced by the writer Marcel Proust, as he explains, “It’s the most serious part of my personality. It’s a very simple Hungarian moustache. Mr Marcel Proust used the same kind of pomade for this moustache.”

A 2008 biopic film titled Little Ashes, was made in tribute to Dali’s early career, with Robert Pattison playing the artist as a young man.

In his later years, Dali began to collaborate with Disney on a short film inspired by Fantasia, titled Destino. Sadly the film was never realized in his lifetime, but it was completed by Disney’s nephew Roy in 2003, resulting in a six-minute animated short.

Dali’s ongoing love of money led him to con various people out of large sums of cash. He once fooled a buyer into purchasing his painting at an extortionate price, saying paint had been mixed with the venom of a million wasps. While artist Yoko Ono bought what she thought was a strand of his moustache for $10,000, unaware it was a dry blade of grass from his garden.

As a way of avoiding restaurant bills in his later years, Dali would doodle on the back of his checks. He was so famous by then, he assumed no one would cash in a check with an original Dali drawing on the reverse, allowing him to nab a free meal.