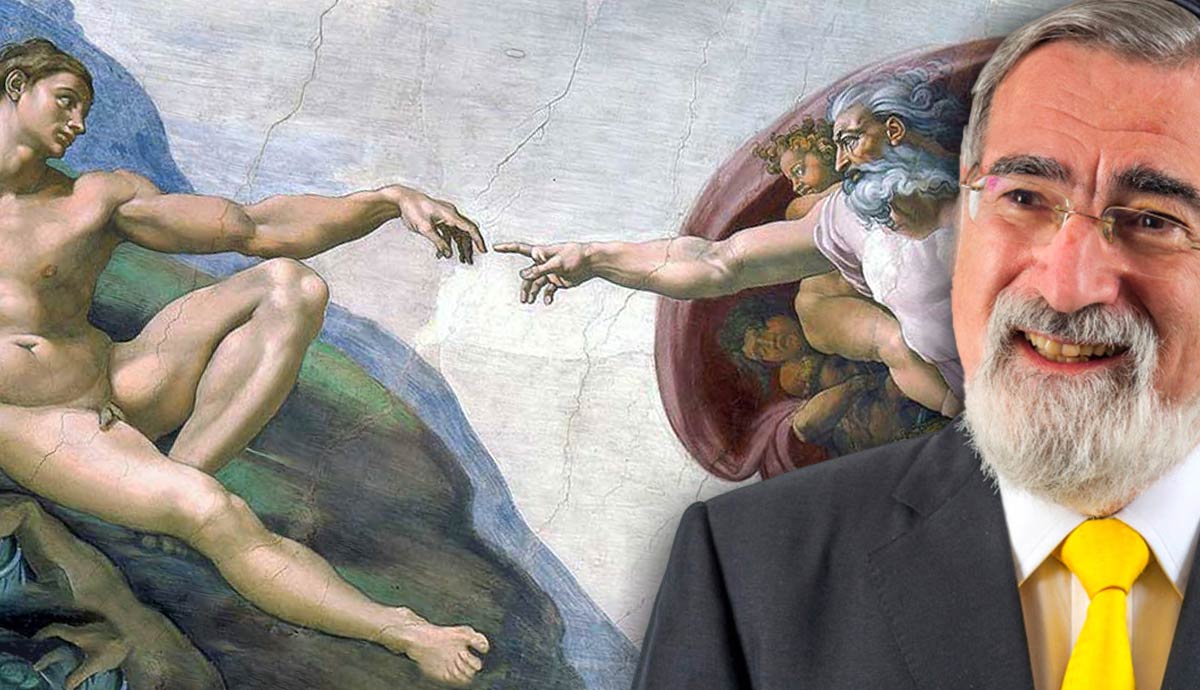

In his book, The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning, Jonathan Sacks writes against thinkers of the new atheism (like Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, or Daniel Dennett). He is determined to show that religion is not replaceable by science and that religion is essential to grasp human meaning. Against new atheists, he believes that existential questions are key to our freedom and hope. He also believes that any narrative of the universe that does not account for purpose is ultimately a tragic one.

How Do Science and Religion Interact? Four Different Models

According to Dr. Denis Alexander, the relationship between science and religion can be represented in different models. No model truly encapsulates the colorful interaction between the two but highlights a dimension of it.

As he mentions, science and religion are already intricate enterprises, and “both are in a constant state of flux.” (Alexander, 2007, p. 1) Notwithstanding complexity, these models tell us something about the position of an author.

There are four models, according to Alexander. First, we find the conflict model, according to which science and religion are constantly in disagreement and are opposing enterprises.

Secondly, there is the NOMA model. NOMA means Non-Overlapping Magisteria, as initially proposed by paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. In his view, science and religion address separate kinds of questions and work within isolated compartments; no conflict is present because of this definition (Alexander, 2007, p. 3).

Thirdly, the fusion model represents the opposite of NOMA, claiming that there is no dividing line between science and religion. For example, insights from quantum mechanics can be said to resonate with Eastern religious beliefs in a way in which they are intertwined.

Finally, the Complementary model “maintains that science and religion are addressing the same reality from different perspectives.” They complement each other (2007, p. 4). Let us keep these different models in the back of our minds as we discuss Jonathan Sack’s approach. In the end, I would like to consider which model better represents the ideas of the Orthodox rabbi.

Jonathan Sack’s Take on Meaning

The central claim of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks is that “science takes things apart to see how they work. Religion puts things together to see what they mean” (2012, p.

64). Let’s try to unpack this statement by reconstructing his argument focusing on the first part of his book The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning.

One initial premise of Sacks is that human beings are qualitatively different from the rest of nature. Humans are not simply part of nature; rather, they have something that transcends it. If this were not the case, says Sacks, then humans would lack any uniqueness; there would be nothing distinctive about humanity, and “our hopes, dreams and ideals” would be reduced only to brain processes (2012, p.119).

Darwin went even further and defended that humans were not only not created in the image of God but “they were just one branch of the primates, close cousins to the apes and chimpanzees” (2012, p. 121). For Jonathan Sacks, this is unacceptable because pivotal concepts such as human dignity and freedom hinge on the uniqueness of humanity.

Secondly, God “is not to be found in nature for God transcends nature” (Sacks, 2012, p. 82). This means that God is not reducible to any material principle or law. He argues that the discovery of Monotheism (the belief system that holds the doctrine or concept of the existence of only one supreme deity, God, or divine being) is key.

Monotheism is not simply the opposite of polytheism. He rebukes, “We make a great mistake if we think of monotheism as a linear development from polytheism, as if people just worshipped many gods, then reduced them to one” (2012, p. 16).

Instead, Monotheism recognizes that God is outside the universe and is able to create it. Notice that this already restricts his argument to three Abrahamic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. I will come back to this idea.

Given the two premises, Jonathan Sacks can contend that while science is about explanation, religion is all about meaning. In a nutshell, while science is concerned with the physical dimension of nature and humanity, religion provides meaning to it.

Cognitively speaking, they perform different activities: “Science analyses, religion integrates. Science breaks things down into their component parts. Religion binds people together in relationships of trust. Science tells us what is. Religion tells us what ought to be” (Sacks, 2012, p. 14). This is why the existence of God can never be proven because it is asking science to deal with an object that lies outside its domain (2012, p. 19).

If science and religion have distinct functions, then it follows that to believe in God is not a denial of science. Both are essential aspects of human expression and experience.

Why Science Cannot Provide Us With Meaning

For Sacks, the meaning of a system lies outside that system. This implies that science cannot answer questions of meaning. It can only describe the system. He gives the example of a football match. One can describe the rules of the game, but the meaning of the game (the why) is found outside the rules, namely, in the wider social context of people enjoying it.

Science deals with the internal logic of the system and religion with what lies outside of it. In this vein, the orthodox theologian can assert: “The meaning of the system lies outside the system. Therefore, the meaning of the universe lies outside the universe.” This has a substantial consequence: if humanity were to toss religion aside and focus only on science, it would lose all meaning.

It would entail that everything beautiful about humanity is devoid of real significance, that “they are fictions dressed up to look like facts. We have no souls” (Sacks, 2012, p.

26). Nihilism is the only outcome of renouncing religion “A world without religious faith is a world without sustainable grounds for hope” (2012, p. 18). There is nothing in science that can provide meaning, it only offers bleak explanations.

Left-Brain and Right-Brain Cultures

Both science and religion are essential perspectives. Their function is similar to that of the right and left hemispheres of the human brain. Therefore, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks is not arguing against science.

Human life would be deprived without either of those dimensions. He further explains: “The left hemisphere tends to be linear, analytical, atomistic and mechanical (…) The right brain tends to be integrative and holistic” (Sacks, 2012, p. 47).To be sure, he is not saying that the two hemispheres are completely independent. He is using them as metaphors for different modes of engagement with the world.

He further argues that this contrast between the left and the right hemisphere is related to the Greek tradition and the Hebrew tradition, respectively. For example, when the Bible wants to account for the phenomenon of Monarchy it does not discuss in the line of Plato and Aristotle “the merits of monarchy as opposed to aristocracy or democracy (…), it does not articulate theory. It tells a story” (2012, p. 50).

For this reason, Jonathan Sacks regards Greece as a left-brain civilization while Israel is a right-brain culture; the Greeks “worshiped human reason, Jews, divine revelation” (2012, p. 52).

Two Shortcomings of Jonathan Sack’s Ideas

Once we have outlined the premises and conclusions of the argument, it is worth highlighting some of its shortcomings. For Sacks, denying any metaphysical principle in humanity leads to devaluating society and individuals. He explains that if no metaphysical principle is recognized, “Humans might write novels, compose symphonies, help those in need, and pray, but all this is a delicately woven tapestry of Illusions” (2012, p. 27).

But this conclusion does not follow. The complexity and beauty of human achievements are valuable in themselves. He also criticizes what he would deem a material reductionism of humanity: “For thoughts are no more than electrical impulses in the brain, and the brain is merely a complicated piece of meat, an organism” (2012, p. 27).

Once again, the complexity of the brain —and the whole body, for that matter— is not given sufficient credit to the extent that even today, we still do not comprehend everything about it (Hawkins, 2021). On the other hand, even if one disagrees with the lack or presence of a metaphysical principle, this does not entail simplicity of material organization and emerging properties.

Sacks also claims that the meaning of the system lies outside of it. For him, meaning is something that is discovered and, to be precise, is only found in the monotheistic God. This disregards many other spiritual traditions that are not transcendental, i.e., in which meaning lies within the system.

Furthermore, the lack of a preexisting meaning does not necessarily conclude in nihilism, as he suggested. Meaning can be constructed, for example, besides our loved ones and communities, thus leading us to a fulfilling life. The atheist physicist Stephen Hawking, when referring to all his ideas of the universe adds: “It would be an empty universe indeed if it were not for the people I love and who love me. Without them, the wonder of it all would be lost on me” (2020, Chapter 3).

Even with these caveats, the claim by Jonathan Sacks is powerful, namely, that science and religion are two different cognitive activities that are nevertheless complementary.

Indeed, science takes things apart to see how they work, and religion puts them together to see what they mean. They both produce valuable types of claims necessary for a richer view of reality. He is right in arguing that science has inherent limitations and that there are domains in which a scientific approach is not the answer.

Left-brain people like Stephen Hawking inadvertently accepted that limitation. While recalling some early stages of his life, Hawking narrates: “I was always very interested in how things operated. I used to take them apart to see how they worked but I was not so good at putting them back together again” (2020, Chapter 3).

Literature

Alexander, D. (2007). Models for Relating Science and Religion. Faraday Institute for

Science and Religion, 3. https://www.faraday.cam.ac.uk/wp-

content/uploads/resources/Faraday%20Papers/Faraday%20Paper%203%20Alexand

er_EN.pdf

Hawking, S. W., Redmayne, E., Thorne, K. S., & Hawking, L. (2020). Brief answers to the big questions (Paperback edition). John Murray (Publishers).

Hawkins, J. (2021). A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence. Basic Books.

Sacks, J. (2012). The great partnership: Science, religion, and the search for meaning (First paperback edition). Schocken Books.