The Swedish abstract art pioneer Hilma af Klint is usually perceived as a reclusive occultist who was completely immersed in her spiritual exploration and disconnected from the outside world. However, she was very much involved in the social and scientific life of her day. Many of Hilma’s works referenced scientific discoveries of the time, or directly developed from studies of botany, physics, and technology. Read on to learn more about the scientific roots of Hilma af Klint’s art.

Hilma af Klint’s Early Career and Aspirations

Swedish artist Hilma af Klint was born in the mid-nineteenth century into a dynasty of marine officers and cartographers. From an early age, she expressed interest in natural science and drawing, inspired by the cartographic works of her family members. Her family was rather supportive of her decision to become an artist. Sweden was one of the first countries to grant women rights to obtain higher education, including art-related degrees. However, despite the legal action, the everyday discrimination did not go away so easily. In the opinion of many public figures, women artists were incapable of innovation and could only copy the styles and subject matter of men.

Despite the stereotypes and institutional obstacles, Hilma af Klint finished art school and was awarded her personal studio in central Stockholm. For decades, she made a living by painting portraits and creating illustrations for botanical and zoological encyclopedias. Not all of her works have been identified throughout the years since many of them remained unsigned. Illustration was her most publicized domain of work, yet it was not the type of art that brought her widespread fame. Inspired by the explorations of the spiritual, Hilma af Klint started to create abstract art in her early forties. However, her illustrations would play a surprisingly important role in her non-figurative career.

The History of Scientific Illustration

The tradition of scientific illustration goes back into the centuries of exploration of the natural world. Before the significant developments in photography, illustration was the only possible way of preserving objects of study and recording their appearance. Even today, scientific illustration is still widely used in educational materials. Compared to photography, illustration can focus the reader’s attention on particular features or small details more clearly, partially omitting irrelevant parts.

In its purpose, scientific illustration was radically different from traditional expressive art, since it diminished the role of the artist, turning them into a passive receptive instrument. To create a quality illustration suitable for learning and research, an artist had to abandon their aspirations, ideas, and stylistic influences in favor of precision and thorough observation. In a state close to meditative, an artist examined every leaf, fruit, or seed in order to catch every bit of tone and texture. Scientific illustration left no room for artistic experimentation but it certainly required great concentration and a clear state of mind. During HIlma a Klint’s time, this kind of illustration was deemed suitable for female artists since it objected to innovation and experimentation.

Science in the Age of the Occult

The end of the nineteenth century was the prime time for the development of numerous spiritual and occult theories and ideas. Contrary to popular understanding, they did not contradict science and even relied on it to a certain extent. The discovery of invisible particles and the inventions of the telephone and photography challenged the traditional relationship of people with time and space. Overwhelmed by the possibilities of the intangible world, some fell into the crisis of faith, while others became entirely convinced of the existence of higher powers. People from the latter category moved on to develop spiritual theories and practices. They wanted to construct a new relationship with the unseen realm.

Spiritual seances were a popular hobby that could supposedly connect the living with someone dead, addressing their soul and mind in the world of spirits. Although these seances were often labeled as fraudulent, some researchers believed they were real, and even wrote extensive treatises on the matter. Various theories, such as Mesmerism, were based on the idea of challenging energies and the unseen vital force in the right direction, resulting in healing. For a short while, material data could co-exist with spiritual one and the two even propelled each other’s development. Some of the brightest minds of the era, including Arthur Conan Doyle and Thomas Edison were members of spiritualist clubs.

Leap to Abstraction

The tendency towards de-figuration of art was common among many progressive artists worldwide. Around the same period, artists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky started to experiment with the gradual reformation of their imagery, aiming it toward a complete dissonance with the physical world. Many such artists felt the need to justify their explorations and legitimize them, accompanying visual experiments with theoretical work. Kandinsky’s writing Concerning the Spiritual in Art, for instance, offered a detailed theoretical explanation of the supremacy of the spiritual component in art and the necessity to let go of recognizable imagery in order to progress as a society.

Hilma af Klint, however, followed a different path. She hardly ever attempted to justify her practice in front of large audiences and certainly did not require widespread acceptance. Her move towards non-representational imagery happened through spiritual seances and trances. According to artists, she received a task to record coded spiritual knowledge in the form of paintings and pass it to further generations.

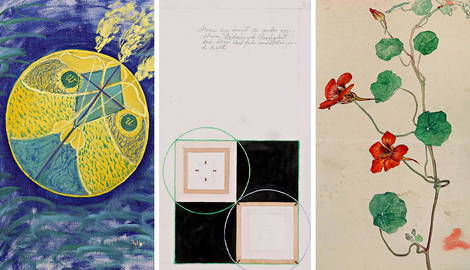

The result was the large-scale project Paintings for The Temple, a series of 193 paintings realized under the supposed guidance of spirits. In these works, af Klint deliberately stepped back as an independent creator, allowing the supernatural forces (or her subconscious, as the Surrealists would say) to take control. Just like with the botanical illustration of her early years, af Klint’s artistic ego was unnecessary during such a task. Paintings for the Temple were pure data devoid of interpretation and were accompanied by diaries in which Hilma attempted to systematize symbols and details. She insisted that her works were painted by her hand, but not by her, as she believed that she was channeling someone else’s will.

Science of the Unseen

After the Paintings for the Temple were finished, Hilma af Klint felt the need to define the field of her exploration on her own terms. Starting from 1912, she gradually broke contact with her spiritual guides, instead relying on her own methods and ideas. She introduced Christian symbolism, explored spirituality through music (like in the series Parsifal which is based on the musical drama of the same name by Richard Wagner), and experimented with forms and mediums in her works. Raised in the tradition of nineteenth-century science, af Klint used its conceptual apparatus and applied it to metaphysical concepts widely and sometimes unexpectedly.

One of her lesser-known series titled Standpoints was a visual retelling of the values and worldviews of several religious and spiritual groups, formulated in black-and-white circular diagrams. Decoded in lines and circles were the standpoints of Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Paganism, and Theosophy. Contrary to popular belief, the artist never disconnected herself from the outside world, keeping track of the latest scientific discoveries and events. Her 1917 series Atom was a direct reaction to the 1910s developments of atomic theory and the discovery of isotopes.

Hilma af Klint’s Later Years: Return to Botanical Illustration

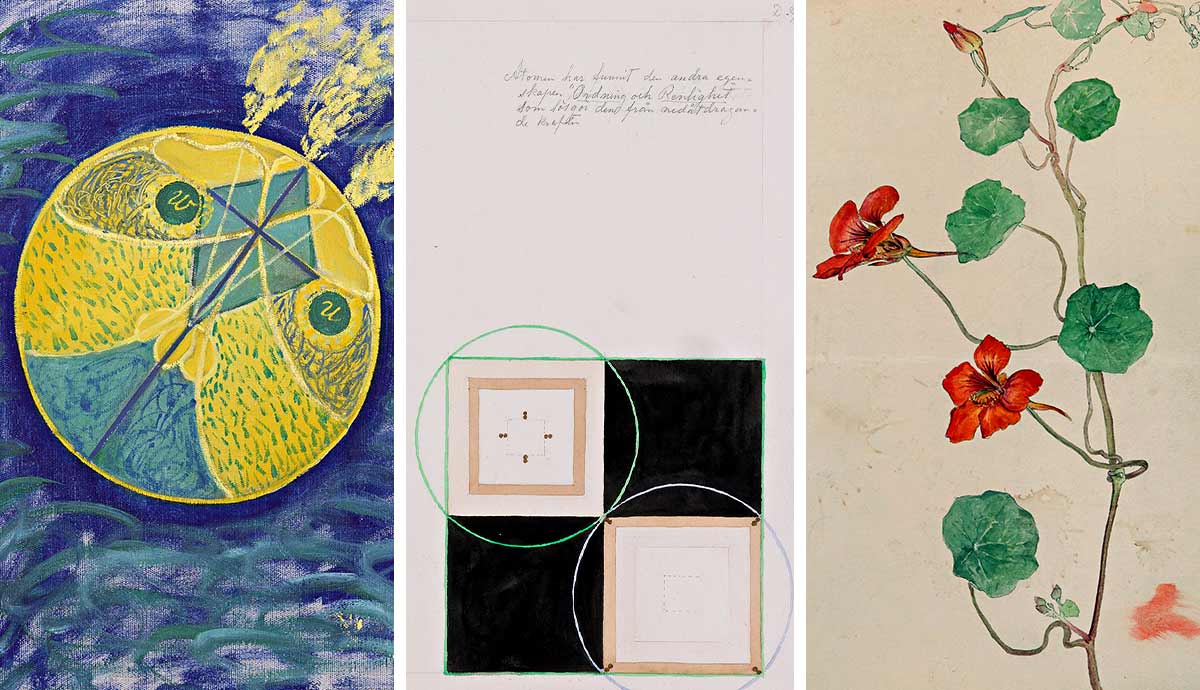

In the later years of her career, Hilma af Klint left ambitious large-scale projects behind and focused on albums and visual atlases painted using watercolor. Once again, she turned to botanical illustration, this time augmented by her spiritual and scientific knowledge. Starting from the 1920s, she worked and studied in the library of the Goetheanum, the headquarters of the Anthroposophical Society which represented a Christianity-based alternative to Theosophy. She even gave lectures on her spiritual explorations and her art.

Hilma af Klint’s early illustrations made a surprising comeback in her later works, with precisely copied images of flowers, mosses, and tree leaves appearing on the pages of her notebooks again. This time, however, precise and detailed drawings were accompanied by small square diagrams, reflecting the energetic field of a plant and its position in the spiritual world. These works were not artistic in their nature but rather explorative. The artist recorded and investigated forces and energies she believed were invisible to the human eye, but noticeable to her.