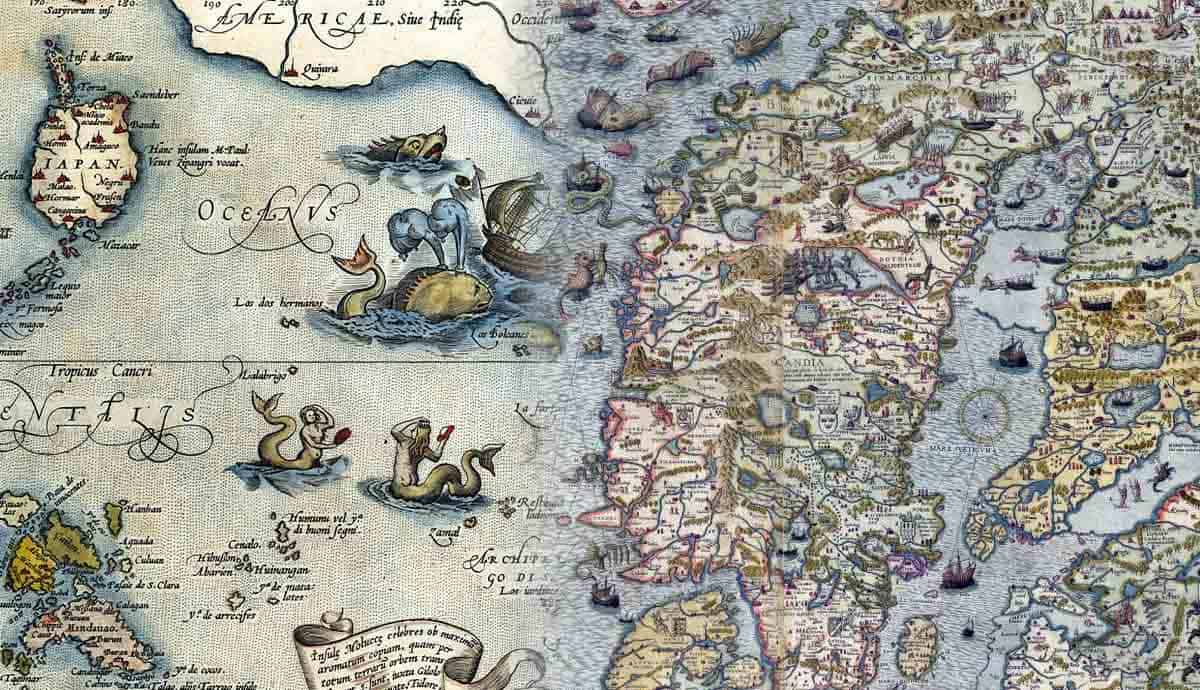

One of the most striking features of Renaissance maps are the sea creatures embedded in their cartography. More than just decorative elements, they represent what people truly believed was out there swimming in the deep. Our past relationship with the ocean is also revealed, with maps representing changing perspectives of this untameable element of nature. A vast array of mythical sea monsters are depicted, from the siren to the leviathan. Each tells its own tale of both the experiences of explorers as well as the perceptions of those on land.

The Role of Maps in the Renaissance

During the Renaissance, maps were used for purposes beyond the navigational. Instead, many were utilized as art objects, often displayed in people’s homes to exemplify their wealth. Among the aristocracy, they were used to help carefully construct an identity within society. Commissioning a map was a way of showing wealth and power through the ownership of an expensive object, as well as control over the land depicted.

As a result, the aesthetics of many maps moved beyond the geographical, displaying decorative elements including people, ships, and sea monsters. Such maps can be dissected as art historical objects; they allow us to gain insight into the imaginations of people during this period, from the patrons of the maps to cartographers, sailors, and the general population.

Three primary types of maps existed during the Renaissance: nautical maps, world maps, and those derived from Ptolemy’s Geography. While nautical maps were primarily used for navigation, world maps were often held by private collectors for display in their homes. These maps were people’s main source of information about the rest of the world, including the creatures of the oceans.

Renaissance Perceptions of Marine Life

By the time of the Renaissance, the dominating perception of the ocean was that it was an unruly force that needed to be tamed by humans. It was the Age of Exploration and the rich and powerful in the West sought ownership and control of much of the globe. This included the so-called “high seas,” a name from the Old English “heahflod” meaning “deep water,” given to the seas outside of a country’s territorial control.

Maps were used to display landed possessions, however, the ocean too, was a place for domination. While local peoples likely posed the largest threat in uncharted lands, the deep ocean was filled with natural dangers. Alongside the threat of stormy seas, or getting lost, sailors lived in fear of sea monsters which lived in the deep.

Sailors’ stories of sea monsters often stemmed from folklore and Biblical stories. However, sometimes they mistook animals, particularly whales, for sea monsters. Cartographers drew on these stories when creating their maps, using the monsters for decoration. In particular, they were used to deter any foreigner from sailing waters which the patron of the map sought to protect.

The sea monsters shown on maps provide useful insight into the minds of those who lived in Renaissance society — both their imaginations as well as their global outlook. The sea monsters present on maps can teach us much about the Renaissance imagination.

Sea Sirens and Perceptions of Women in Society

Stemming from Greek mythology, sea sirens are half-woman, half-fish creatures that lure sailors off their boats and into the murderous depths of the ocean. In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus saved his crew’s lives by blocking their ears so that they were unable to hear the sirens’ irresistible song and he tied himself to a mast in order to prevent himself from jumping overboard at the sound of their calls.

Alongside classical mythology, religious ideals were also influential. In a time of rampant misogyny and the demonization of the female figure, sea sirens were understood to lead men away from their righteous path into the realm of lust and infidelity. On maps they are sometimes shown holding a fish, the Christian symbol of the human soul, stolen from God and the Christian faith.

Sirens were accepted within society as a serious and real threat. Cartographers picked up on these tales and included them in their maps, often ships, where they put their alluring powers to use.

Images of the sea siren reflect the perception of women in society at the time as being inferior to men. Women had few rights and were seen as the possessions of their husbands. They were required to fit the Renaissance ideal of chastity and motherhood. Any woman who existed outside of that ideal was seen as a threat to men. In particular, the female musician was deemed to have the ability to control men through their music, similar to the sea siren.

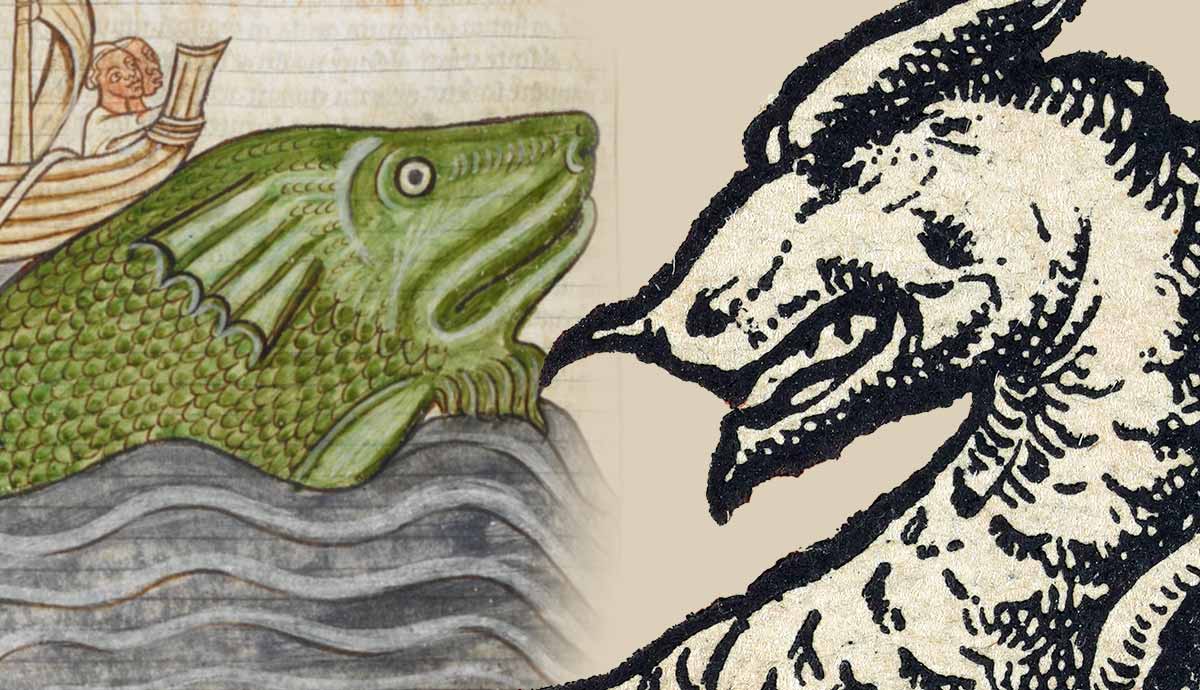

Leviathan and the Role of Christianity

Tales of the Leviathan originated from mythology, with descriptions of it developing over time. By the Renaissance, with the expanded influence of Christianity, its depiction in the Old Testament greatly influenced people’s belief in the monster. It is described as a fierce, untameable beast that cannot be destroyed by man. Instead, it is killed by God, and its body is given as food to Hebrews in the wilderness.

Undertaking work related to the Devil, its primary role was seen to be to punish sinners. It was thought to bring great chaos to the oceans, consuming sailors as they swam through the waves, seeking out evildoing. It supposedly resided in the Mediterranean and is therefore depicted in many Renaissance maps of the region. It is even sometimes shown in murderous action, attacking ships and killing sailors.

As a monster that dwells in the inky depths, Leviathan was feared for its strength, it was thought to be over 300 meters (over 900 feet) tall with impenetrable scales. Sailors stood no chance against this giant creature, and cartographers drew on its ferocity. It was seen as a great force that many believed would attack them from the ocean’s depths. Generally, it reveals the anxieties at the time surrounding sea travel.

Other Sea Monsters

There were other monsters too; pristers, for example, resemble a kind of sea snake and were also shown on maps, attacking ships. Like Leviathan, they were huge beasts — cartographer Olaus Magnus described them to be over 200 feet long and covered in spikes.

Some depictions were more familiar. Cartographers drew fish-like variations on land mammals such as the sea cow, giving them fish tales instead of legs. Monsters could sometimes be large-scale renderings of real animals, such as giant lobsters and giant squid. Existing animals were also included such as walruses and narwhals.

As mentioned, ideas about sea monsters were often based on whales. Whales themselves were regularly included on maps, often with monstrous heads. Alexander The Great’s myth of “the Whale Island” also played out on some maps; like in the tale, they show two sailors resting on what they think to be an island, setting up camp, and lighting a fire. The island soon reveals itself to be a whale and plunges into the ocean, carrying them to their deaths.

The sea creatures depicted in Renaissance cartography were diverse in nature and reveal much about the imaginings of people during this time, particularly sailors. Most importantly, anxieties surrounding sea travel are revealed. It is important to remember that these maps were produced in the Age of Exploration. Sailors were often visiting uncharted waters, in which the fear of the unknown contributed greatly to their experiences of the ocean. This was heightened by the mythology surrounding sea monsters which permeated society.

Ultimately, sea monsters were creatures to be feared that would sink or wreck ships during voyages, or in the case of sea sirens, lure sailors overboard. In particular, Renaissance conceptions of womanhood led to a fear of sea sirens, and Christian values resulted in a belief in the Leviathan. Fear of existing sea creatures, on the other hand, led to exaggerated renderings of them within cartography too.

Toward the end of the Renaissance, when technology was advancing, these sea monsters evolved on maps to represent sea creatures in a more realistic way. The mysteries of the deep disappeared and with them the thrilling tales of the sea monsters that lived within.