Historians grimace at the word “inevitable,” but in the same way that the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 laid the groundwork for further conflict, so too did the treaty between Rome and Carthage that ended the First Punic War.

While Carthage was left damaged territorially, economically, and militarily, it sought to heal. But one family would turn recovery into revenge. The conflict began with Hamilcar Barca, and would see his son Hannibal take the conflict to the Romans on their own soil. The Second Punic War would be devastating for Rome’s armies, but they would eventually beat the Carthaginians into submission for a second time. But it is Hannibal who would earn a reputation as one of the greatest military commanders ever known.

Growing Carthaginian Influence in Iberia

For many Carthaginians, the terms of the Treaty of Lutatius reached with Rome in 241 BCE were egregious. Most notable among the treaty’s detractors was Hamilcar Barca. The general and statesman was undefeated during the First Punic War, but he and the Carthaginians were forced to cede Sicily and Sardinia to the Romans. Hamilcar was not ready to retire and turned his attention to expanding Carthaginian power in Spain.

For centuries the Phoenicians had maintained a presence in the Spanish Iberian peninsula, particularly on the southern coast, establishing trading colonies within its natural harbors.

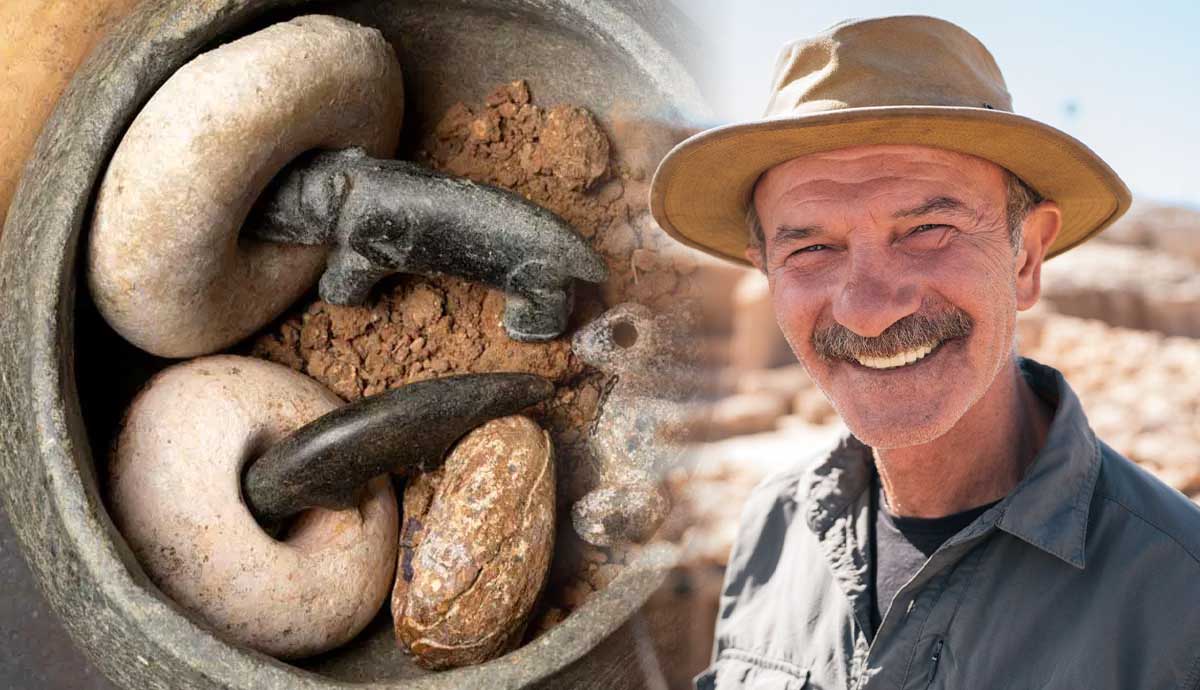

Hamilcar, with the help of his son-in-law Hasdrubal and his young son Hannibal, carved out a pseudo-monarchical state on the peninsula. Reaping the benefits of Iberia’s ample silver mines and agricultural potential, the Carthaginians began to regain their commercial strength that had been lost.

The ancient historians Cassius Dio and Cornelius Nepos tell us that it was on one of these Iberian campaigns that Hamilcar fell in battle at the hands of a people called the “Vettones.”

Despite the death of the patriarch, the Barcid’s power persisted under the command of Hasdrubal. Wary of their old enemies and their growing power, the Romans signed a new treaty with the Carthaginians in 226 BCE to establish the boundary of Carthage’s sphere of influence at the Ebro River in northern Spain.

Hasdrubal’s time in Iberia was cut short by his subsequent death. His successor would have little respect for boundaries, and far less for Romans.

Provoking War

The ancient historian Polybius attributes these words to Hannibal as evidence of Hamilcar’s indoctrination of his young son against Rome.

“When my father was about to go on his Iberian expedition I was nine years old: and as he was offering the sacrifice to Zeus I stood near the altar… he then bade all the other worshippers stand a little back, and calling me to him, asked me affectionately whether I wished to go with him on his expedition. Upon my eagerly assenting, and begging with boyish enthusiasm to be allowed to go, he took me by the right hand and led me up to the altar, and bade me lay my hand upon the victim and swear that I would never be friends with Rome.”

Born in the waning years of the First Punic War, Hannibal would be raised in a society that had been thoroughly humbled by the Romans. From an early age, Hannibal was on campaign with his father. Spain became his training ground, leading the cavalry and learning the ways of war.

Taking over for his brother-in-law, Hannibal was leery of moving on the town of Saguntum (modern Valencia) before he was totally prepared. The Saguntines had entered talks with the Romans despite the town lying south of the Ebro River. According to the treaty of 226 BCE, Saguntum lay within the Carthaginian sphere of influence. Nevertheless, Hannibal besieged the city in 218 BCE, simultaneously claiming the role of liberator and attacker.

The Saguntines resisted, hoping that a Roman relief army would appear as an answer to their letters. It never came. Hannibal stormed the city and wiped out the entire adult population. Rather than an army, Rome sent a declaration of war.

The March Into Italy

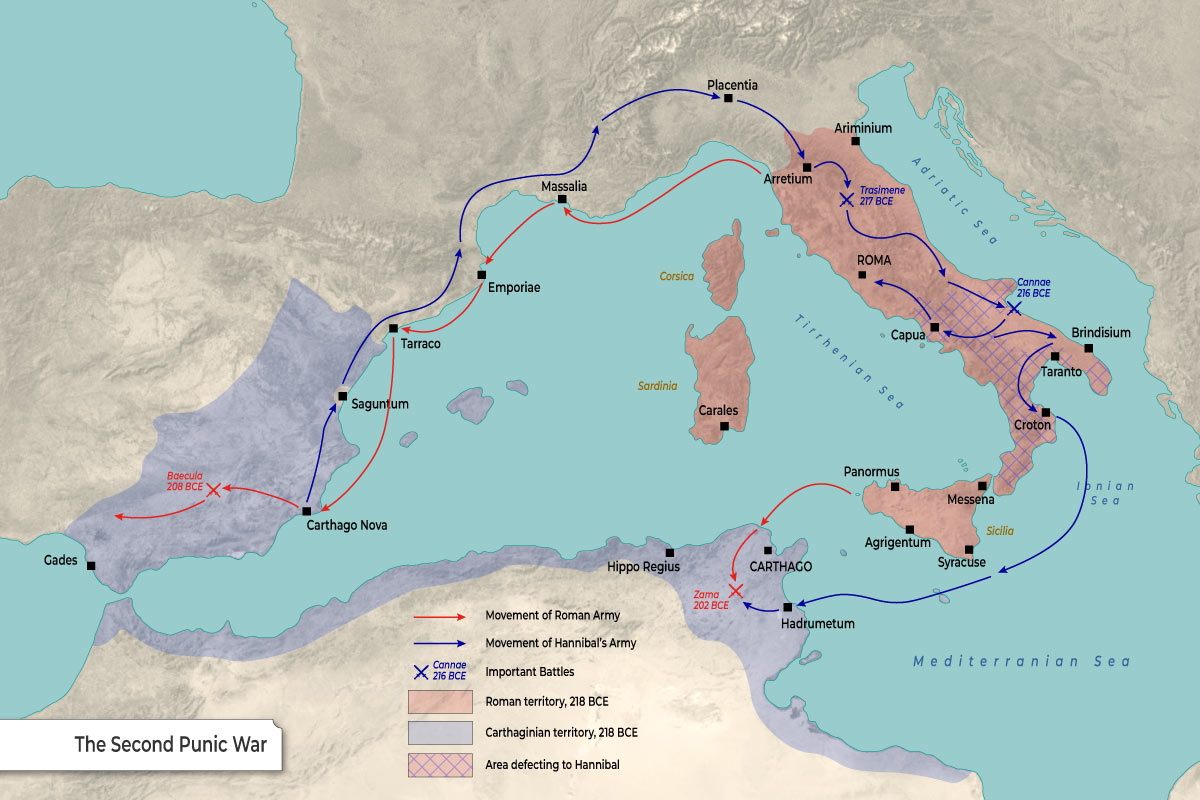

Hannibal wasted little time. He had learned the lessons of the First Punic War and was unwilling to let the Romans fight on the offensive in Iberia, or even worse, in Africa. Bereft of a navy by the terms of the Treaty of Lutatius, he gathered his forces at Nova Carthago (modern Cartagena), and decided to take the war to the Romans and march overland to Italy.

He began his journey crossing the Pyrenees and coming into contact with many Celtic tribes, whom he had hoped to recruit to his cause. The Romans, hearing of his progress, made plans of their own. They deployed one consul, Publius Cornelius Scipio, to Iberia, and the other, Tiberius Sempronius Longus, with the invasion of Africa.

As Hannibal crossed the Rhone River, Scipio disembarked his men at Massalia (modern day Marseille), assuming that Hannibal’s march would follow the coast. The two armies’ cavalries skirmished briefly, but Hannibal side-stepped the larger engagement, and despite the onset of winter, disappeared into the Alps.

Harried by treacherous footing, fickle Gallic tribes, brutal cold, and thick snow, Hannibal marched his army through the Alps. For two weeks they suffered, losing many men, horses, and war elephants to ambushes, starvation, freezing temperatures, and steep cliff faces. Finally, his army began their descent into Italy. Having circumvented Scipio’s army, Hannibal appeared in the province of Cisalpine Gaul (modern-day northern Italy) with 20,000 infantry of varying ethnicities including Libyans, Iberians, Numidians, and Gauls.

First Battle of the Second Punic War

Now November 218 BCE, no one had foreseen Hannibal’s audacity. Still short of his 30th birthday, Hannibal had made an enormous gamble. His army had been battered, exposed to the elements, and left short of food. But they were now on Roman soil.

Publius Scipio scrambled back from the Rhone Valley to try to head off Hannibal once again. Alerted by the oncoming dust cloud of the cavalry, each side prepared for what would become known as the Battle of the Ticinus River. Promising his men grants of land, money, or citizenship, Hannibal exhorted his men onwards, arranging his Carthaginian cavalry in the center and his Numidians on the flanks.

Scipio, holding a low opinion of the Numidians from their skirmish in the Rhone Valley, advanced. The Roman javelinmen (velites) hurled their projectiles at the enemy line and quickly retreated. A stalemate developed until the Numidians, using their famed mobility, circled around the flanks and hit the Romans in the rear. Panic ensued as the lightly armed velites were cut down by the horsemen.

As the Numidians closed in, Publius Scipio was wounded and Hannibal was close to sealing his victory with the death of a consul. Had it not been for a stunning act of bravery by the consul’s son, also named Publius Cornelius Scipio, who rode through the enemy lines to save his father, Hannibal’s victory would have been complete. Albeit stunned, the Romans retained their consul, and withdrew.

Panic in Rome and the Battle of the Trebia River

Following this defeat on Roman soil, panic ensued in the Roman Senate. Sempronius Longus was recalled to defend Italy. He rushed north to join his consular colleague, the wounded Scipio, who, despite his defeat, had continued to shadow Hannibal’s army.

Having captured a grain depot at Clastidium in Cisalpine Gaul, Hannibal approached the River Trebia in December 218 BCE. Holding the high ground on the other bank, Longus and Scipio funneled cavalry of their own across the shallow river to meet Hannibal’s Numidian scouts. Unprepared for a serious engagement, the Carthaginians withdrew, under a hail of javelins, having lost a significant number of men to the quick-acting Romans.

With Scipio still too ill to lead the men himself, Longus sought to escalate the engagement with Hannibal, despite Scipio’s weary words of warning.

Picking a thicket sufficient to conceal part of his army, Hannibal laid his trap. He sent a contingent of Numidian horsemen across the river to draw out the Roman forces. Longus hastily took the bait. He drew up the entirety of his consular army (approximately 40,000 men: four legions and 20,000 socii allies) and advanced across the river despite the cold and driving rain.

Hannibal arranged his men, 20,000 infantry of Iberians, Celts, and Libyans, in one long line with his Numidians and war elephants on either wing. Hannibal allowed Longus’ advance guard to draw near. Once the signal was given, the Carthaginian army descended upon the Romans. It was then that Mago, Hannibal’s brother, emerged from the thicket with his own forces, attacking the Romans from behind.

Seeing their flanks crumbling, the rest of the Roman army (perhaps as much as half according to Polybius) was cut down and trampled by the Numidians and war elephants as they tried to flee back towards the river. The combined consular army of Scipio and Longus was halved before midday.

The War Reaches Italy: The Battle of Lake Trasimene

With two victories now in hand, the Carthaginians broke camp for the winter in June 217 BCE and began their march south. Hannibal circumvented the Romans yet again by trudging through uninhabitable marsh and appearing in Etruria (modern Tuscany and Umbria). His daring maneuver worked but he lost the function of one eye to disease.

Outside the walls of Arretium (modern Arezzo), Hannibal, famous for his insight into the personalities of his Roman counterparts, knew that the new consul, Gaius Flaminius, holed up behind the walls would not be able to sit back and watch as he ravaged the countryside.

Flaminius sallied out and chased after Hannibal, who had positioned himself in the hills surrounding the town of Cortona. His troops overlooked a valley and a thin road on the banks of Lake Trasimene. This created a defile that would force opposing troops to march in a narrow column. Shrouded amongst the undulating hills, the Carthaginian army stretched the entire length of the defile, waiting for the eager Flaminius to fall into the trap.

The next morning, Flaminius came upon the defile. With the hills further shrouded by a persisting misty rain, Flaminius marched his army down the narrow road. When the bulk of the Roman army was confined within the defile, Hannibal gave the signal to attack, and “delivered an assault upon the enemy at every point at once” (Polybius).

The Roman soldiers were set upon so quickly that many did not have a chance to defend themselves. They were cut down where they stood. Others were pushed into the lake, or jumped in and began to swim, only to be dragged to the bottom by their heavy armor.

When the mist broke, a small group of Romans, who had managed to push their way out one end of the narrow passage, looked back and saw the devastation that had occurred. Over 20,000 of their comrades lay dead, including the consul Flaminius.

The Fabian Strategy

Word of Flaminius’ carelessness soon made it back to Rome. The annihilation of yet another army “threw the city into a great commotion,” according to Plutarch. In their desperation, they appointed a dictator to serve for the term of six months. The man they chose was Quintus Fabius Maximus.

Having seen the devastation Hannibal had wrought, Fabius concluded that to confront him was suicide. Instead, supply lines would be cut, foraging parties intercepted, farmsteads or other potential sources of supplies would be burned, but Hannibal was not to be engaged directly.

For Fabius, the only prudent course of action was to let the effects of disadvantageous terrain, hunger, and time slowly whittle down and break apart Hannibal’s multinational coalition. Hannibal knew that, given enough time, Fabius’ strategy could obstruct his ultimate goals. He feigned attacks on Fabius, continually trying to draw him out. But Fabius waited patiently until Hannibal finally made a mistake.

Mixing up the name of a nearby town, Hannibal marched his men into a valley surrounded on all sides by mountains. Fabius sprung into action, blocking off the pass and stationing his skirmishers on the high ground. Thinking they were completely surrounded, the Carthaginian army began to waver.

Hannibal, however, steadied his men, instructing them to tie torches to the horns of cattle. They drove the beasts of burden, at first slowly, towards the Roman lines, imitating the form and pace of marching soldiers. When the wood burned down and hit the skin of the oxen, they jolted forward, throwing themselves in an anguished panic at the Romans. While the Romans broke rank, Hannibal slipped through their grasp.

Roman Forces Divided

With his men hungry and feeling vengeful, Hannibal ravaged the countryside, making certain that Fabius’ country villa remained intact, implying a secret coalition between the two.

Many Romans had had enough of the eponymous “Fabian Strategy.” They called him cowardly, “Hannibal’s pedagogue,” cunctator (the delayer), all for his stubborn refusal to attack the enemy even as the countryside burned.

Chief among the critics was his second-in-command Marcus Minucius; the magister equitum (master of horse). Contrary to Fabius’ orders, Minucius attacked the Carthaginian camp while Hannibal was away. This victory, albeit small, was lauded by the Roman Senate. Fearful of Fabius’ power to punish his subordination, the senate voted Minucius equal powers to the dictator. With the Roman forces now divided and Hannibal well aware of the animosity between the two men, he seized the initiative. Hannibal split the forces of the Romans by occupying a hill in between them.

During the night, Hannibal stashed a contingent of men behind the undulating terrain, out of sight of either Roman force. In the morning, he challenged Minucius to battle. Minucius obliged and the two forces fought savagely for sole possession of the hill. As Hannibal’s cavalry squeezed the heavy Roman infantry, the signal was given for the hidden Carthaginian contingent to emerge and hit the Roman flank. As Minucius’ forces crumbled away, Fabius, the ever-cautious commander, mustered his men and made a desperate march to save his colleague. The ever-prudent Hannibal, knowing he was outmatched, quickly withdrew.

Fabius’ quick reaction prevented a larger disaster. But it would not matter. Rome was tired of his perceived inaction. His term expired and he was maligned rather than praised for keeping the war effort afloat. The only man that seemed to see the prudence in Fabius’ strategy had just slipped through the Roman’s fingers yet again.

A New Roman Army and the Battle of Cannae

With Fabius out of the way and a winter to regroup, in August 216 BCE the Roman war machine roared back to life. While Fabius had waged his guerilla war against Hannibal, the Senate issued a decree to muster an unprecedented eight new legions. With this massive force, the Romans sought to bring Hannibal to heel once and for all at the battle of Cannae.

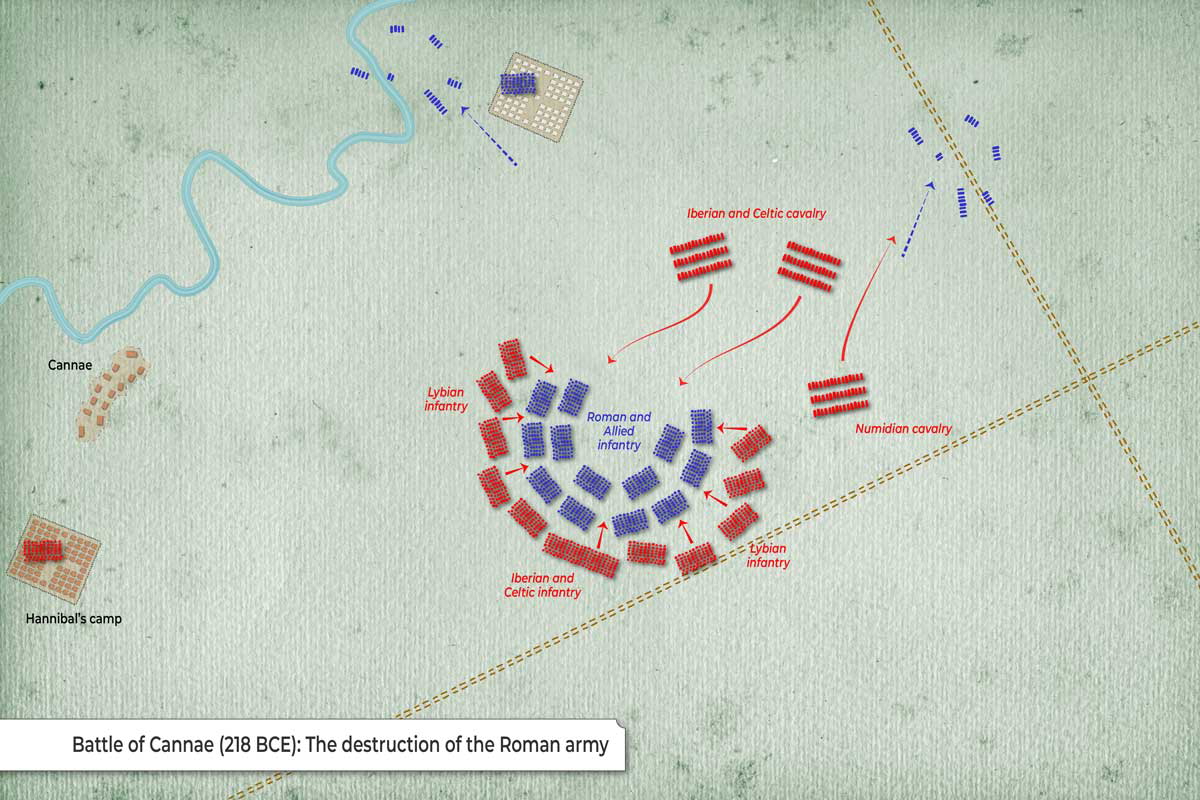

For the task at hand, they assigned the two consuls, Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro. They marched towards Hannibal’s encampment. Paullus urged caution, citing the long, flat plain in front of them. Hannibal’s Numidian cavalry would be too effective there. As was the custom, however, the command of the army when two consuls were present switched off each day. Ignoring his colleague, Varro ordered an advance. With cavalry on his flanks, Varro stacked the maniples with greater depth to take full advantage of the weight of his numerical advantage.

Hannibal, whose army made up little more than half of the Romans, countered with his Iberian and Celtic cavalry alongside the river on his left, his heavy Libyan and Celtic infantry, wearing Roman armor taken from the dead at Trebia and Trasimene, in the middle, and his Numidians on the right. Rather than a standard battle line, Hannibal arranged his men in a convex formation, the belly of the arc pointed directly at the Roman infantry.

The Darkest Day

Under a hail of projectiles launched by his Balearic slingers, Hannibal’s cavalry slammed into their Roman counterparts on the wings. The Roman cavalry collapsed and the Carthaginians gave chase, leaving only the infantry on the field.

Varro’s massive columns marched directly at Hannibal’s crescent formation, hoping to overwhelm it with sheer numbers. As the two lines met, Hannibal’s center slowly gave ground, drawing more and more Romans into the fray. Even as their center gave ground, Hannibal’s flanks held. Varro, hoping to smash through the Celtic center and encircle the rest of Hannibal’s army, fed more men into the breach.

Hannibal’s arrangement now became concave with the Roman’s pushing so deeply into the center that the Libyans on the flanks were now behind them. As Hannibal had planned, the Libyans turned inwards and the Numidians hit the Romans in the rear and completed the encirclement.

With so many men in such a dense formation, the enveloped legions were compressed to the point that they could lift neither shield nor sword to defend themselves. For hours the Romans could only wait to be cut down or trampled. The largest army in Roman history was slowly and methodically massacred.

Not until the mechanized killing of the 20th century, would the world see such a bloody day. Polybius tells us that by the end of the day, 70,000 Romans were killed or captured. Yet another consul, Lucius Paullus, was killed in action.

In two years, since his arrival in Roman territory, Hannibal had reduced Rome’s male population by 20%. To put that in perspective, during the Great War, France lost nearly 5% of its total population in four years.

The War in Spain: A Battle of Brothers

Having failed to defeat Hannibal at the River Ticinus, Publius Cornelius Scipio and his brother Gnaeus were sent to Iberia to disrupt the base of Carthaginian power from which Hannibal had launched his invasion.

In 211 BCE, the Scipio brothers redoubled their offensive. Publius led his forces against Hannibal’s brother Mago while Gnaeus took the remaining Romans and Celtiberian mercenaries against another Hasdrubal Barca. Deceitful tribesmen and Carthaginian bribery left the two Roman armies isolated. Publius found himself ambushed, and in a daring night escape, he was slain by a javelin. Like carrions circling their prey, the three Carthaginian armies engulfed the remaining legions under Gnaeus.

Without competent leadership, the Iberian front was on the verge of collapsing. Eager to prove himself and reclaim his family’s honor, the younger Publius Cornelius Scipio, son of the now dead Publius, appeared before the Comitia Centuriata (committee of centurions) and was unanimously elected to lead. Known for saving his father’s life at Ticinus, the youth was still only in his mid-twenties. A veteran of Ticinus, Trasimene, and Trebia, the younger Publius had experience, but had seen only defeat.

The wide dispersion of the three main Carthaginian armies in Iberia led Publius to adopt a bolder plan of action. Unlike his uncle and father’s campaign, which had lasted for seven seasons, Publius sought to strike a decisive blow. He set his eyes on the Carthaginian regional capital: Carthago Nova.

Coordinating his attack with the Roman navy, Scipio launched a feint to pull the defenders away from the north wall. As Roman casualties mounted, a group of 500 soldiers waded across a lagoon at low tide and seized the undefended gatehouse.

Scipio now possessed a major logistics hub on the southern coast of Iberia. It would be a perfect stepping stone for what he had planned next.

The Sword of Rome and the Siege of Syracuse

During the long reign of Hiero II of Syracuse (Sicily), the Syracusans had been a staunch ally of the Romans. Following the Roman defeats and the death of Hiero in the following year, Syracuse descended into chaos, second guessing their alliance with Rome. It was in this chaos that Marcus Claudius Marcellus, elected consul for a third time in 213 BCE, was sent to Sicily. A veteran of the First Punic War, Marcellus was an experienced statesman, soldier, and winner of Rome’s highest honor, the spolia opima.

Marcellus surrounded Syracuse, bringing the full might of Roman engineering to bear against its massive walls. Plutarch tells us that large siege towers, fastened to the decks of his warships, were sailed into the harbor. Countering Marcellus and his great machines of war was the famed philosopher and mathematician Archimedes. Plutarch reports an iron claw, wielded from the walls, plucking Roman ships from the water and large projectiles being hurled at the attackers, convincing them they were fighting “against the gods.”

The siege dragged on for months. It was not until a diplomatic ceasefire was called and the stalemate was broken. As Marcellus entered the city to parlay with the stubborn defenders, he noticed a vulnerability in the defenses. Taking advantage of the festivities of a public sacrifice, Marcellus made his move and entered the city with a small group of men.

Unaware of the Roman infiltration, no defenses were marshaled. It is said that Archimedes was killed in the middle of a particularly thorny mathematical problem. Having lived in the squalid conditions of siege for over a year, the Romans burst into the city with rapacious zeal. The city, known for its beauty, exquisite works of art, and great wealth, was summarily looted. So great was the theft and influx of Greek art into Rome that Marcellus was credited by Plutarch with teaching “the ignorant Romans to admire and honor the wonderful and beautiful productions of Greece.”

The Final Battle at Zama

The war entered its 15th year in 203 BCE. Following his successes in Iberia, Scipio sought to end the war decisively, eying Africa. There were many in Rome who thought this was too risky, given Hannibal’s continued presence in Italy.

Scipio embarked on his plan, landing in Africa with 25,000 men. Hannibal was recalled by the Carthaginians, and the two men, having fought each other at the Ticinus River, were to meet on the plains of Zama, on Carthaginian soil, to decide the fate of the war.

At the battle of Zama, Hannibal’s force was pieced together from three separate armies. In the front, he placed his 80 war elephants and his mercenaries. Behind them were the Carthaginians and Libyans, and in the rear was his army that he brought with him from Italy. Battle-hardened and undefeated by the Romans, they were to prevent a retreat by the less experienced men.

As the two armies marched towards each other, Hannibal sent his war elephants charging at the Roman infantry. The Roman skirmishers parted, leaving gaps in their lines for the elephants to charge through. As they passed, the great beasts were inundated with projectiles, sending them into a frenzied stampede back into the Carthaginian lines.

Then, the first line of each army charged. The hastati (infantry) and the mercenaries careened into one another. Panicked by the Romans’ discipline and order, the mercenaries fled, leaving Hannibal’s Libyans to meet the oncoming threat. They pushed the Romans back before Scipio sent his principes (legionaries) into the fight. Hannibal’s third line of veterans steadied the line, but the advancing Romans proved too much. Coupled with the timely return of Massinissa, a Numidian king allied to Scipio, the Carthaginians were routed.

The Death of Hannibal

Following the Battle of Zuma, Carthage capitulated. But Hannibal would remain a prominent figure, serving as a sufete (Carthiginian magistrate) in 196 BCE. Despite the financial burden of Rome’s war indemnity, he was able to return a level of solvency to the state. Nevertheless, many Carthaginians remained hostile to the Barcid name.

Hannibal advocated for term limits on the judges that served in the Court of the Hundred and Four from life to one year in an attempt to break the oligarchic grip the body had on Carthage. This was seen as too drastic by those in power and he was duly exiled.

He found refuge in the court of the Anatolian Seleucid king Antiochus III, serving him in his ongoing conflict with the Romans. Following a naval defeat, he fled yet again to Bithynia, in modern-day Turkey. He was received at the court of Prusias. Cornelius Nepos tells us that during a diplomatic dinner in Rome, an envoy of Prusias let it slip that the Carthaginian resided in Pontus with the king. The Romans immediately intervened, sending soldiers to surround the complex where Hannibal lived. Prusias was incapable of denying the Romans, and while they stormed his citadel, Hannibal uncorked a small bottle of poison which he always carried with him and emptied the poison into his mouth.

According to Livy, as he died, Hannibal said: “Let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man’s death.” Never forgetting the oath he made to his father, Hannibal, the greatest enemy of Rome, took his own life, unwilling to ever submit to the Romans.

Rome Unreachable

After Hannibal’s victory at Cannae, the road to Rome lay open. Instead of marching on the capital of his sworn enemies, Hannibal, known for his aggressive maneuvers, paused. Stunned by this, his cavalry commander, Maharbal, remarked, “Hannibal, you know how to gain a victory; you do not know how to use it.”

However, Hannibal knew the truth. He could not take the city. No matter how many consuls he killed in the field, there would always be another. Then there were the walls of Rome itself, too formidable for his small, albeit experienced, and undersupplied army.

Chastised by his fellow Romans, Quintus Fabius had been right. He knew the advantages of fighting a war on your own soil would be too much for the Carthaginian, as brilliant as he was. It would not be until the discovery of gunpowder that the walls of the Roman capital would finally fall.

The Romans had a history of stubbornly refusing to give in to external threats. After their disastrous defeat at the Caudine Forks in 321 BCE, the Romans spurned peace talks with the Samnites and war would rage for two decades. In the third century BCE, the fatiguing victories of the invader Pyrrhus of Epirus would not coax the Romans to the bargaining table. Pyrrhus left the Italian peninsula exhausted. After watching multiple fleets sink to the bottom of the sea in the First Punic War, the Romans raised yet more and more ships. In Rome’s darkest moments, when Hannibal approached the very gates of the city, they did not yield. It was Roman conviction and stubbornness that saw them through to victory.