Sekhmet was the ancient Egyptian goddess of war and healing. She was also the patron deity of physicians and healers, and could both spread disease and cure it. Equally feared and worshipped, the lioness Sekhmet was without a doubt one of the most prominent goddesses in the Egyptian pantheon. In this article, we will take a look at her character, the myths about her, and explain why the Egyptians called her Bloodthirsty.

1. Sekhmet Was an Aspect of Hathor

The Egyptian pantheon possessed a great number of powerful goddesses. The most well-known is of course Isis, the Great Sorceress and mother of all gods. But Hathor, goddess of love and music, had a far bigger following in ancient times. She took several different forms, most of them very wholesome and protective of the people of Egypt. But whenever Hathor was angry, she would take the form of the lion headed goddess Sekhmet, the Bloodthirsty, a frightening deity who fed on the blood and fear of her enemies.

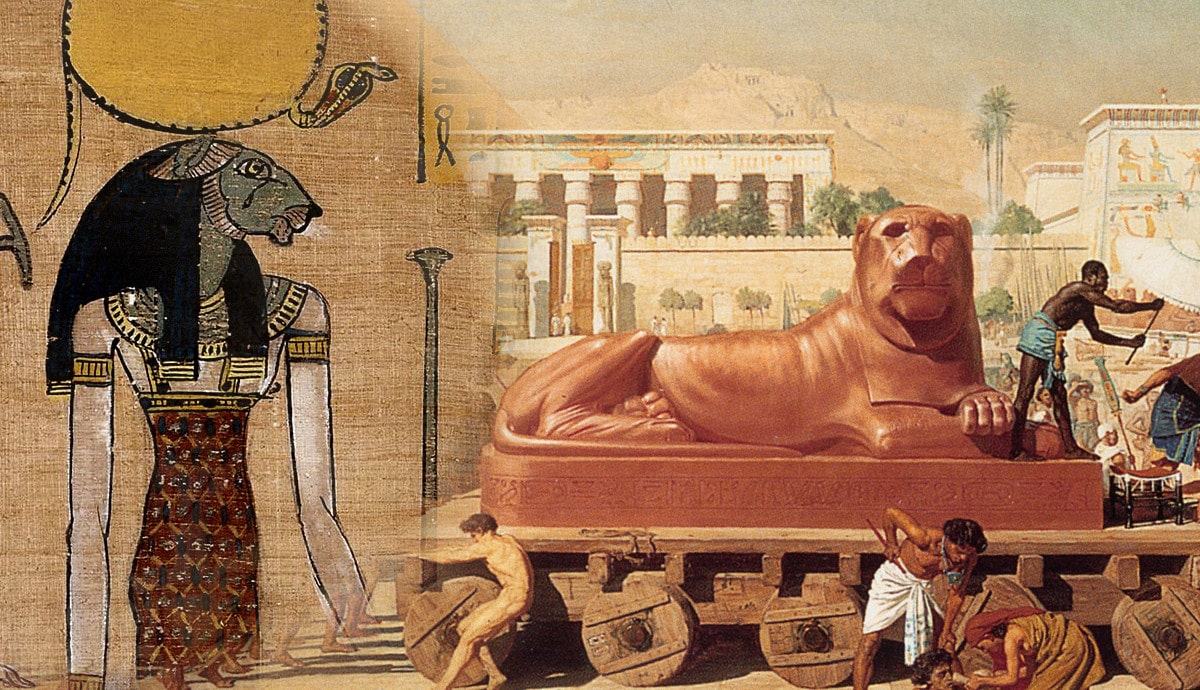

In Egyptian art, Sekhmet was depicted as a woman with the head of a lioness, and sometimes her skin would be painted green, like Osiris. She carried an ankh sign on her left hand and a long-stemmed lotus flower on her right hand. Her head was crowned by a large sun disk, relating her to the sun god Ra, and an uraeus, the serpent associated with Egyptian kingship.

Sekhmet’s name comes from the adjective sekhem, meaning “powerful” or “mighty”, while the ending –t is a suffix for female names. Of her many epithets, all were equally terrifying. She is sometimes referred to in Egyptian texts as “She Before Whom Evil Trembles”, the “Mistress of Dread”, “The Mauler”, or the “Lady of Slaughter”.

Although she was born as an aspect of Hathor, over time both goddesses evolved into completely separate Egyptian deities, mainly because their characters were so different from each other. During the Middle Kingdom, Sekhmet became associated with Bastet and other feline goddesses and absorbed the attributes and identity of Mut, goddess of creation.

2. She Was Important in Memphite Theology

The origins of the Egyptian goddess Sekhmet are unclear, but she seems to have been born in the Delta area, where lions were rarely seen and were thus regarded as mysterious and magical beasts. According to an important text about Memphite theology engraved in the famous Shabako Stone, the lioness Sekhmet was the wife of Ptah, patron god of artisans, and the mother of the lotus god Nefertum. She was also the firstborn of the sun god Ra. During the New Kingdom, Ra, Sekhmet, and Nefertum became known as the “Memphite Triad.” They were adored as a group during the times of Egyptian history when Memphis was the capital of Egypt, especially the 18th and 19th dynasties, right until the reign of Seti I (715-664 BCE).

She was also revered as the “Mistress of Asheru” in the Mut Temple, at Karnak, and her cult was strong in the regions of Luxor, Memphis, Letopolis, and all the Delta. At some of the temples there, she was offered the blood of recently sacrificed animals, in order to placate her rage. If her anger was contained, it gave her worshippers control over their enemies and the vigor and strength to overcome weakness and illness.

Priests would perform rituals before a different statue of this Egyptian goddess every day, to appease her considerable anger. This is the reason why so many different Sekhmet statues and images have survived from archaeological sites. In Amenhotep III’s temple there have been found as many as 700 statues of Sekhmet. In Leontopolis (the city of the lion, in Greek) some sources inform that there were tamed lions and lionesses kept captive as living images of Sekhmet.

3. Sekhmet Was Called the Bloodthirsty

Sekhmet was known to enjoy the taste of blood. Every year, on the feast of Hathor and Sekhmet, Egyptians commemorated the saving of mankind by drinking copious amounts of beer stained with pomegranate juice. The surviving records of such feasts talked about how they did so to worship “the Mistress and Lady of the Tomb, the Gracious One, Destroyer of Rebellion, Powerful with Enchantments.” During the celebrations, a statue of Sekhmet was dressed in red facing west, while one of Bastet was dressed in green and facing east. Bastet was considered to be Sekhmet’s counterpart or twin, and during the festival, they embodied duality, which was an important concept in Egyptian mythology. Sekhmet represented Upper Egypt, while Bastet stood for Lower Egypt. Bastet was the tame, good goddess, while Sekhmet was the Bloodthirsty, the chaotic and dangerous deity of war and love.

Such a bad reputation was awarded to this Egyptian goddess due to a myth in which she had threatened to wipe out humanity. The only thing that prevented her from ending humanity was getting drunk on beer, which had been dyed red as blood. Thus, during her annual festival, held at the beginning of the year, Egyptians danced, played music, and intoxicated themselves in an attempt to soothe the wrath of the goddess. This ritual had another meaning, too, and that was to prevent the excessive flooding of the Nile, which ran blood-red every year, carrying upstream silt.

4. Sekhmet Was a Goddess of War

With her violent and vicious reputation, it was only logical that Sekhmet became associated with war activities. Sekhmet was adopted by many Egyptian pharaohs as a military patroness, for she was said to breathe fire against the enemies of Egypt. Banners and flags would march into battle with depictions of Sekhmet, symbolizing the might of the pharaoh in battle. In a statue erected at the Mut Temple, Karnak, she is referred to as the “smiter of the Nubians.” During military campaigns, the hot desert winds were considered to be the breath of Sekhmet, and after each battle, celebrations would be held in honor of Sekhmet, so she could be appeased and would not continue with her destruction. The powerful pharaoh Ramesses II proudly wore the image of Sekhmet as a symbol of warring power. In the friezes of the Battle of Kadesh, at Karnak, Sekhmet is depicted riding Ramesses’ horse, scorching the bodies of their enemies with her flames.

5. If She Wasn’t Happy, Sekhmet Spread Disease

In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, there are multiple mentions of Sekhmet as both a constructive and destructive force. But even in her destructive facet, she is, above anything, the keeper of cosmic balance or Ma’at. However, sometimes, she tried too hard to keep the balance between life and death, resorting to extreme practices to control the population. Plagues in ancient Egypt were often called “messengers” or “slaughterers” of Sekhmet, for they were supposed to follow her commands. One interesting passage of The Story of Sinuhe said that the fear of the king “overran foreign lands like Sekhmet in a time of pestilence.” This is because she was known as “Lady of Pestilence” and the “Red Lady,” alluding not only to blood but to the red land of the desert. Making Sekhmet angry was known to bring plagues and diseases upon those who dared provoke her.

6. Sekhmet Was Created to Cause the Destruction of Mankind

In Egyptian mythology, there is a long and interesting tale in which the story of Sekhmet is told. It is known as The Destruction of Mankind, and it appears just at the beginning of a longer myth named the Book of the Heavenly Cow. Of course, the “heavenly” cow is the Egyptian goddess Hathor. This story is written on a funerary papyrus from the New Kingdom (1539-1292 BCE), and the tale it tells is extraordinary.

At the beginning of time, the story goes, when gods lived among men, a rebellion aimed to overthrow Ra, the creator god and king of the gods. Despite being a god, Ra had become old, and grew weaker every day, until humans decided he was not fit for ruling over them. Before this insurrection, Ra had been ready to give up the throne and return to the Nun, the primordial ocean. But now he was angry at humankind, and took one of his eyes from which Ra created the Eye of Ra, which was one manifestation of Sekhmet. He then ordered the eye to strike the seditious men with a heat of the sun: “The desert was dyed red with the human blood, while the Eye was pursuing traitors and killing them one by one. It didn’t stop until the sands were covered with bodies. Then, temporarily satiated, Sekhmet returned triumphantly to her Father.”

Sekhmet continued to kill every man and woman in sight for the next few days, but at one point, Ra considered that it had been enough punishment, and decided to spare the rest of humanity. The problem now resided in how to stop Sekhmet from fulfilling her task. Ra ordered the Eye of Ra to stop the killing to no avail, “his Eye had tasted human flesh and she liked it. She decided to kill again.” The only way to stop Sekhmet from killing was to get her drunk with beer, her favorite drink.

Ra brought a red pigment from the desert and ground it into a fine powder, which he mixed with the beer. He then made seven thousand red-beer jars and poured them into the Nile. When Sekhmet saw the red liquid, she thought it was blood, so she drank it eagerly until she was too drunk and fell asleep. When the Egyptian goddess finally woke up, she had forgotten about her purpose of killing every single human being, and felt satiated. She then returned to her father, Ra, who welcomed her back and rewarded her for her services.

7. Sekhmet Was Also an Egyptian Goddess of Healing

Until now, we have emphasized most of Sekhmet’s destructive qualities. But she was, as most Egyptian gods and goddesses, very ambiguous. She was capable of unimaginable cruelties, she had enough power to destroy humankind, and she had a good side too. As we have seen, this Egyptian goddess was closely associated with kingship. In some written sources from the Old Kingdom, she was described as the mother of an obscure lion deity named Maahes. Maahes was a patron and protector of the pharaoh. In the Pyramid Texts, a corpus of early writing very hard to interpret, it is said that the pharaoh himself was conceived by Sekhmet. This is in turn confirmed by a number of depictions of Sekhmet nursing different pharaohs, such as Nyuserra (5th dynasty), but also very late kings like Taharqo. In the Temple of Seti I, one of the finest examples of New Kingdom architecture, there are reliefs depicting the pharaoh being suckled by Hathor. Just below this image, a hieroglyphic inscription reads: “Hathor, mistress of the mansion of Sekhmet.”

One of the epithets of Sekhmet was that of “Mistress of Life.” Because she was capable of spreading disease, she also had the antidote for them. Her healing virtues were so appreciated and respected that Amenhotep III (c. 1390-1353 BCE) had hundreds of statues of Sekhmet made, to place in his funerary temple in the Western Bank near Thebes. They were supposed to protect the pharaoh in the Afterlife, should he need any medicine or healing. Egyptian healers and physicians also valued the protection of Sekhmet, especially those who cared for the king.

Amulets depicting Sekhmet were worn to invoke protection in a variety of forms, against disease but also against more general dangers. Eye of Ra symbols were worn for similar reasons and also closely linked to the goddess.