Shahzia Sikander is an artist who is in constant dialogue with multiple timelines. In her works, the Pakistani artist references the miniature painting tradition of South Asia. We see an age-old genre grappling with issues of gender, religion, and migration through new contemporary artworks. Read on to learn more about the Pakistani artist Shahzia Sikander who is reinventing miniature painting.

Shahzia Sikander: Experimenting with Miniature Painting

The miniature is the oldest and richest figurative painting tradition in the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Indian Subcontinent. It belongs mostly to the pre-colonial past, but some contemporary artists from Pakistan now focus on adding it to modern forms as well. A course in Miniature Painting at a prestigious government art college in Lahore brought about a very interesting artist. In 1987, Shahzia Sikander began studying miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore. She is known as the pioneer of the neo-miniature movement, under the tutelage of Ustad Bashir Ahmed. Her training under Bashir Ahmed largely followed a traditionalist tone. She even had to catch squirrels whose fur was to be used to make brushes.

Sikander uses traditional materials and techniques such as vegetable dyes, tea stains, Wasli papers, and watercolors. On the other hand, Sikander’s practice sets a new tone for understanding miniature painting as a platform for contemporary innovation and artistic virtuosity. Sikander brings together artistic histories by way of layering and superimposing.

In her work Perilous Order (1997) the layers come to life speaking in their own languages. We see a gentleman portrayed in traditional style. There are also nymphs who look upon him, stylistically much older than the man. The painting also leans toward abstraction with rows of dots forming a grid. Perilous Order is an exercise in structural devices crafting a chaos of order.

Who’s Veiled Anyway?

When Sikander first moved to the United States for a master’s program at the Rhode Island School of Design, she struggled greatly with issues concerning identity. She sought to challenge the western image of the veiled Muslim woman. Even though she had never worn the veil, she began to experiment with wearing it and observing people’s reactions.

This experiment led to her painting Who’s Veiled Anyway (1997). At first, the protagonist appears to be a veiled female, but upon noticing carefully another figure resurfaces. This second image is that of a male polo player, a common character in Asian Miniatures. This makes the subject androgynous and creates a feeling of freedom that’s often not associated with Muslim women.

Extraordinary Realities

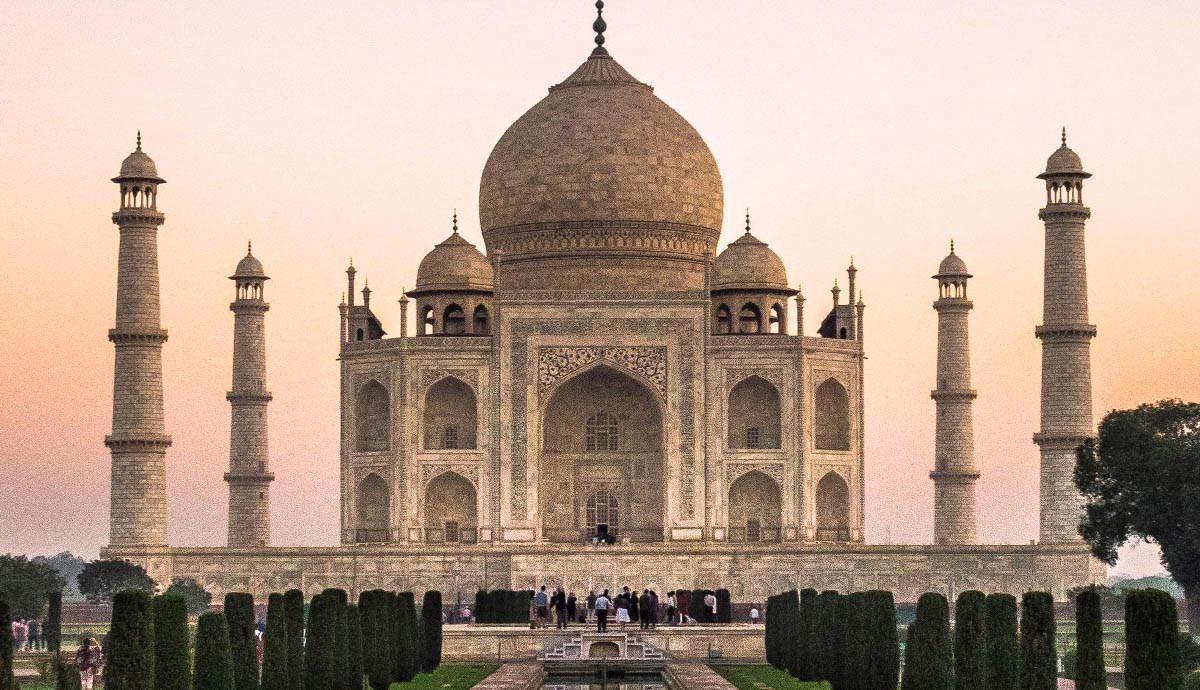

Miniature painting has often been regarded as part of the exotic Other in Western art history. Sikander cleverly questions this exoticization of the form and the form’s own history of technical mastery. In her series called Extraordinary Reality, the artist linked her work to the Indian tourist miniatures, mass-produced by artisans who paint Mughal scenes in Urdu and Persian books. In the series, Sikander repainted some of the most technically accomplished images among Mughal miniatures. She then pasted photographic cutouts of herself onto them. The series became a complex dialogue between photography and painting, the original and the fake, and artist and artisan.

Fleshly Weapons

Although indirectly Sikander often grapples with religious and national tension in the subcontinent, especially between India and Pakistan. She doesn’t combine Hindu and Muslim images into an idealistic national culture, but arranges them side-by-side, juxtaposing their presence. In Fleshly Weapons, Sikander places a Muslim woman’s veil atop an armed Hindu goddess. The combination of the two makes up a hybrid figure, reminding us of the hybrid cultural upbringing offered in the subcontinent.

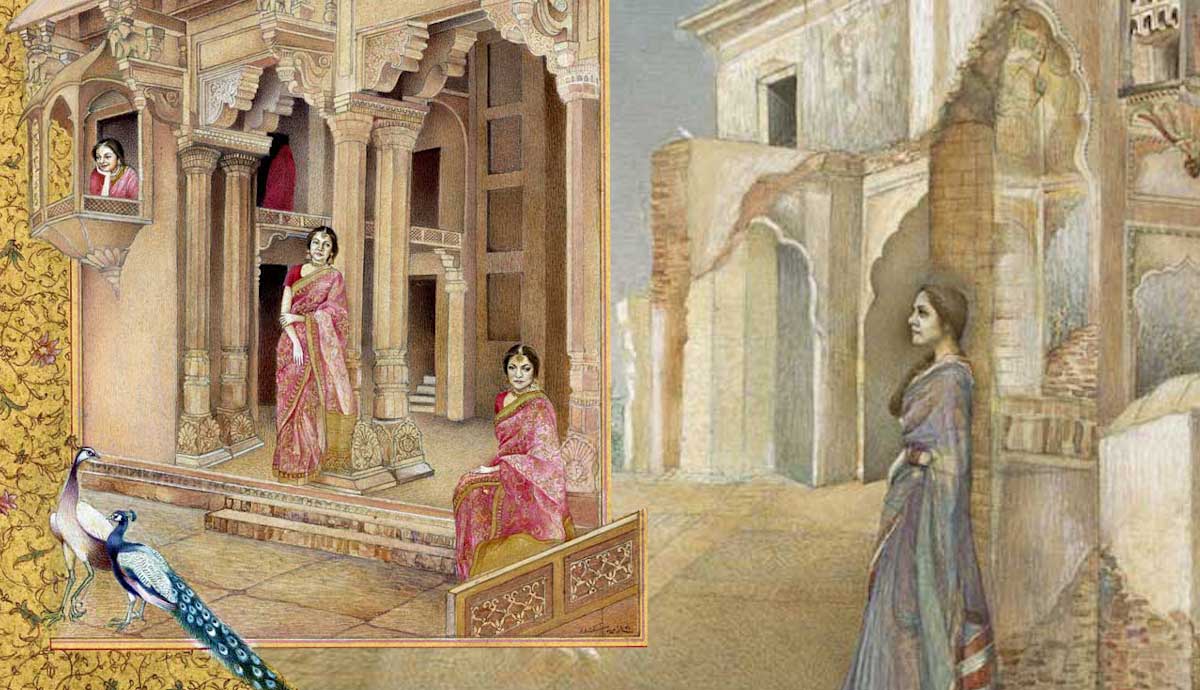

Mirrat I

Sikander has long been interested in the female voice, which has often been excluded from the genre of miniature painting. Sikander’s female figures are neither decorative nor frivolous. They take ownership of their own gaze. The Mirrat series preserves the format of the miniature and its decorative framing, portraying Sikander’s friend Mirrat. In Mirrat I (1989-90) situated at the Lahore Fort, the protagonist looks out at the viewer confidently. She, in turn, is being looked at by the Peacocks wandering outside the painting. Her gestures remind us of stills from 1960’s Pakistani cinema, an era associated with massive social and artistic progress.

Mirrat II and Politicization of the Sari

Mirat I’s counterpart, Mirat II (1989-90) is also set on a site showing historical architecture. The work shows Mirrat in an empty Sikh Haveli, a historical home abandoned after the partition of India and Pakistan. The repetition of Mirrat reflects the passing of time, as traditionally subscribed to Asian miniatures. The outfit worn by the protagonist called the sari represents a very peculiar political gesture. The Mirrat series was made shortly after the death of Pakistan’s military dictator Zia-ul-Haq. Zia’s radical Islamist government had little tolerance for the arts and forced women to dress conservatively.

The sari worn by Mirrat was an outfit worn by many Pakistani women until Zia’s Islamization project. Zia associated the sari with un-Islamic ideals because of its connections to India and Hinduism. Through the subtle sari-clad Mirat, Sikander registers a powerful critique of Pakistan moving away from its roots towards a Saudi-induced religious dogma.

The Scroll

Sikander’s The Scroll (1989-90) breaks the format of miniature painting and instead looks like a long rectangular scroll. This format was often reserved for narrative mythological painting in the subcontinent. Sikander, however, transformed it and made an autobiographical narrative. In The Scroll, the artist takes references from the Safavid painting tradition, depicting herself in a house that reminded her of her teenage home. Giving herself a ghostlike presence, her character moves from one frame to another.

The work largely brings to the surface many layers of domesticity which bind and surround the figure of the female artist, whose liberation lingers and awaits moments of rest. The Scroll reminds us of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, where the author makes her famous argument that a woman must have a room of her own in order to produce artistic work. Similarly, Sikander’s character finds a setting at the end of the scroll after moving around endlessly. In the end, we see her painting her own image on an easel.

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation

After her move to the United States, Shahzia felt like she was often boxed into categories and labeled as either an Asian, Muslim or an outsider. This led to her exploring a new iconography consisting of fragmented and severed bodies. These are often made in androgynous forms, armless and headless, made to look like floating half-human hybrids. The figures directly resist fixed notions and identities. In A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation (1993) a cream-colored headless figure rises against a black background. In its ambiguity, Sikander’s avatar expresses notions of sexuality without narrative footholds.

Gopi Crisis

The tiny female characters in Gopi Crisis (2001) take inspiration from gopis, devotees of Krishna in Hindu mythology. These figures are often depicted as bathing semi-nude in South Asian paintings, with their hair tied in a knot. There is a twist that Sikander introduces. The painting lacks Krishna. Instead, the artist placed fragments of floating shadows. These shadows remind us of the figure seen in A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation. Instead of bathing, the gopis seem to be unraveling each other’s hair, while bats or birds disperse from the painting. Looking closely, we see that these forms originate from the hair of the gopis. The gopis, stripped off of the figure of the god Krishna, now seem to be entering a new world, disintegrating and floating seamlessly.

Shahzia Sikander Forays into New Media with SpiNN

The digital animation called SpiNN is an extension of the Gopi Crisis. The animation takes place in a Mughal durbar, an audience hall, usually presented in typical Mughal miniatures. Sikander replaces the men present in the imperial setting with a huge number of gopis. The authority of the court is therefore replaced with Krishna-less gopis.

Traditional Indian manuscript paintings typically feature a single prominent gopi, Radha, the favored consort of Krishna. As Sikander multiplies the gopis’ numbers, she gives them all the agency of Radha, adding to the power of collective feminine space. These gopis then begin to disintegrate, with their hair swarming off into flocks of birds that completely take over the throne. SpiNN later evolved into a video called Gopi Contagion (2015) that demonstrates ideas connected to swarming and collective behavior. It is interesting to know that Gopi-Contagion was shown on Times Square every night in October of 2015.