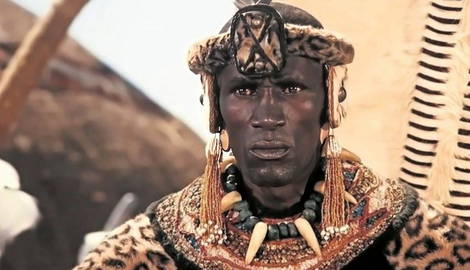

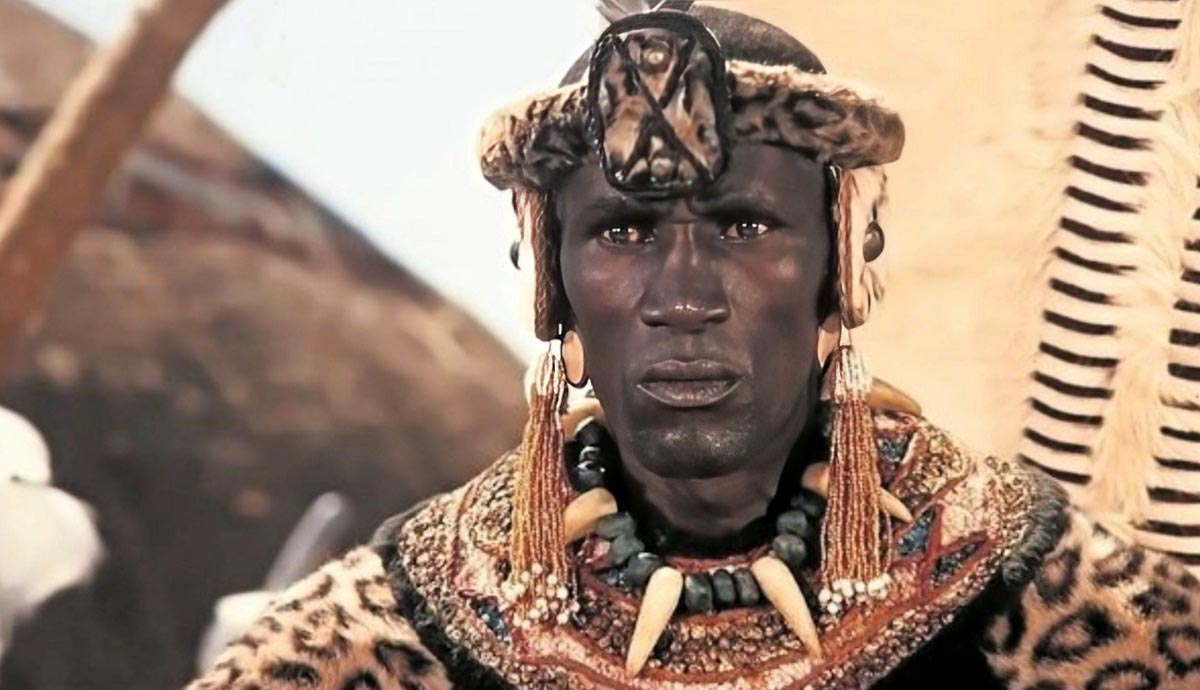

In the early 19th century, in the region of what is now KwaZulu-Natal Province in South Africa, a powerful kingdom was born. At its head was the clever but brutal King Shaka. Under his rule, the small and insignificant Zulu tribe came to dominate all other tribes at a time of immense conflict in the area.

He defined and refined Zulu culture as his conquests created a legacy that exists as a powerful link to the Zulu people today.

His story was one of struggle and violence, as well as immense grief, sadness, and insanity.

The Early Life of Shaka

The birth of Shaka was a result of a violation of Zulu tradition. uKuhlobonga was the act of non-penetrative sex, and it served an important function. The practice was believed to wash away the umnyama – darkness or bad omens caused by killing another man. Thus, when Zulu warriors went to or returned from war, uKuhlobonga was a very common act.

Prince Senzangakhona, chief of the then tiny Zulu tribe, had engaged in uKuhlobonga with a woman named Nandi but had broken tradition and engaged in penetrative sex. To make matters worse, Nandi was from a different tribe, the Elangeni, and engaging in sexual rituals between members of different tribes was also frowned upon.

When Nandi claimed to be pregnant, Prince Senzangakhona dismissed it as an intestinal beetle known as iShaka. As the months passed, it became clear that Nandi was not suffering from an intestinal beetle. When the child was born in 1787, she was sent from her tribe in shame to the Zulu to present her child to Prince Senzangakhona. At first, he denied the child was his, but his uncle pressured him to admit the child as his own, and Prince Senzangakhona relented, admitting he was the father and making Nandi his third wife.

The name Shaka was used in a derogative manner, and as the boy grew up, he was teased and mistreated by Senzangakhona’s other wives and children. Nandi was also the target of distrust and mistreatment.

Despite being the eldest of Senzangakhona’s sons, Shaka would not inherit his father’s title. Shaka’s younger half-brother, Sigujana, would receive that honor.

One day, as an act of revenge, Shaka stood and watched as a dog killed one of Senzangakhona’s sheep. Enraged by Shaka’s inaction, Senzangakhona argued with Nandi and beat Shaka.

Nandi and Shaka left the Zulu tribe and returned to her mother’s tribe, the Elangeni, but they were not welcomed with open arms. The stigma attached to them led them to be treated harshly there too. Nevertheless, they stayed there until 1802, when famine hit the area and forced them to seek help elsewhere.

They took refuge in the mDletsheni clan, which was ruled over by an aging King Jobe of the Mthethwa Paramountcy. Nandi and Shaka were accepted, and Shaka became a cattle herder for the tribe. In 1803, when Shaka was 16 years old, King Jobe died, and his son Dingiswayo ascended the throne.

Under Dingiswayo, the tribe’s focus changed and underwent militarization. Shaka became one of Dingiswayo’s soldiers and showed exceptional ability. Dingiswayo took a liking to this young soldier and promoted him. Shaka eventually became one of Dingiswayo’s generals.

In 1815, King Senzangakhona of the Zulu died after an illness and was succeeded by Shaka’s younger half-brother, Sigujana. He did not reign for long.

With the support of Dingiswayo and the Mthethwa Paramountcy, to which all the tribes in the area belonged, Shaka returned to the Zulu tribe with a regiment of soldiers in tow. He took power in a relatively bloodless coup and had Sigujama put to death. Shaka was now King of the Zulu tribe, which was still a vassal of the Mthethwa Paramountcy.

Shaka Establishes Himself

Shaka quickly proved himself a capable leader and an asset to the Mthethwa Paramountcy. Although heavily militarized, the Zulu did not always resort to warfare to achieve their goal. The Zulu were still small, and Shaka applied pressure via diplomatic means rather than open conflict. Through this tactic, he allied himself with many of his smaller neighbors, primarily to fend off Ndwandwe raids from the north.

Shaka’s accession to the Zulu throne coincided with a period of immense strife within the region. The Mfecane, as it is known by the Zulu, does not translate well into English, but it roughly translates as “scattering, crushing, forced dispersal, and forced migration.” It is also known as the Difaqane of Lifaqane in Sesotho.

The Mfecane is a widely debated topic, and original academic theories posit that it was a result of Zulu expansion, but the theory has been challenged, and evidence suggests this time of strife started at the end of the 18th century before Shaka became king. There was wholesale slaughter and genocide during this period as the region erupted into war, and initial theories put the death toll at between one and two million people, but this figure has been reduced in modern estimates.

War With Zwide

Within a year of Shaka becoming king of the Zulu, Dingiswayo died, murdered at the hands of King Zwide of the Ndwandwe. The Ndwandwe was a rival nation to the Mthethwa, and a war between the two saw a temporary scattering and a power vacuum left within the Mthethwa nation. Shaka stepped in to fill that vacuum and established reforms to reunite the Mthethwa and strengthen its military. Despite being heavily outnumbered by the Ndwandwe, Shaka took the Zulu army and defeated the Ndwandwe.

He defeated Zwide at Gqokli Hill before clashing with the Ndwandwe again at the Mhlatuze River, which proved to be the critical battle that saw the Ndwandwe completely defeated. The massive superiority of Ndwandwe numbers was mitigated by the river they had to cross, and when their army was evenly split on each side of the river, Shaka launched his attack. This battle proved the effectiveness of Shaka Zulu’s strategies and tactics, which he had implemented.

Shaka used the Bull Horn formation to devastating effect. The Zulu army was deployed with flanks (horns) extending from the main body (chest) of the formation, while behind, the reserves (loins) waited to reinforce any area of the main formation. In an era when battles generally consisted of standing in lines and throwing spears at each other, this tactic was innovative and deadly, especially when coupled with the usage of the iklwa – a short stabbing spear instead of the longer assegai. The iklwa is so named as it represents the sound the spear makes when it is pulled from its victim.

It is difficult to determine exactly how Shaka’s revenge came to fruition, but Zwide managed to escape Shaka’s attempt at capturing him.

Shaka was not empty-handed, however. He had captured Zwide’s mother, a sangoma named Ntombazi. According to legend, he locked her in a house with jackals and hyenas, and after she was savaged, he burned the house to the ground.

The remnants of the Ndwandwe fled to the northwest and gave battle once again in 1825 but were finally crushed by Shaka’s army once and for all.

After the war with the Ndwandwe, Shaka continued to subdue the neighboring tribes, often turning to violent conquest in order to do so.

Shaka Meets with Europeans

White traders arrived in Port Natal in 1824, and by this time, Shaka had established a powerful, centralized monarchy. The two Europeans who set out to meet Shaka were Henry Francis Fynn and Francis Farewell. Henry Francis Fynn would end up spending nine years living in Shaka’s kraal, and the two became good friends.

Meanwhile, Shaka had productive dealings with other Europeans. He was visited by Europeans who wished to establish contact and have peaceful relations with Shaka, and Shaka returned the sentiment. He sent a delegation to Major J. Cloete, the representative of the Cape government at Port Elizabeth (part of the British Empire). Favorable relations were established, and Shaka showed immense interest in the technology, culture, and trade that the British brought.

Shaka proved to be generous to the British and ceded land to them to establish a settlement in Port Natal. However, Shaka also built large barracks nearby at Dukuza to let them know that they should not take advantage of his generosity.

The Death of Nandi & Shaka’s Insanity

In October 1827, Shaka’s mother, Nandi, died. This triggered a descent into madness for Shaka, and his behavior became violent and erratic, with the Zulu people bearing the brunt of his questionable decisions. He had people executed en masse for not mourning enough, and he sent his armies out to force other tribes to grieve. Women found pregnant at the time of Nandi’s death were also executed, along with their husbands. Cows were even killed so that their calves could feel what it was like to lose their mother.

He banned the planting of crops and the use of milk for an entire year. This formed the basis of the entire Zulu diet, and famine was sure to follow. This destructive behavior generated massive concern within Zulu society, and within the political echelons, a plot was hatched to depose Shaka.

While Shaka’s armies were away, his bodyguard Mbopha, with his half-brothers Dingane and Mhlangana, set upon him with their spears, murdering the Zulu king. His body was hastily buried in a grain pit, and Dingane declared himself the new king of the Zulu nation. Under his rule, the Zulu would continue the militaristic tradition founded by Shaka and would come into disastrous conflict with expanding European enterprises.

The Zulu Nation would eventually fall to the British in 1879 and thus have barely half a century of independent rule.

Shaka was a complex man. Hailed as a hero by some, and a villain by others, there is no doubt that he made his mark on South African history and created the foundation for the Zulu nation that exists today.