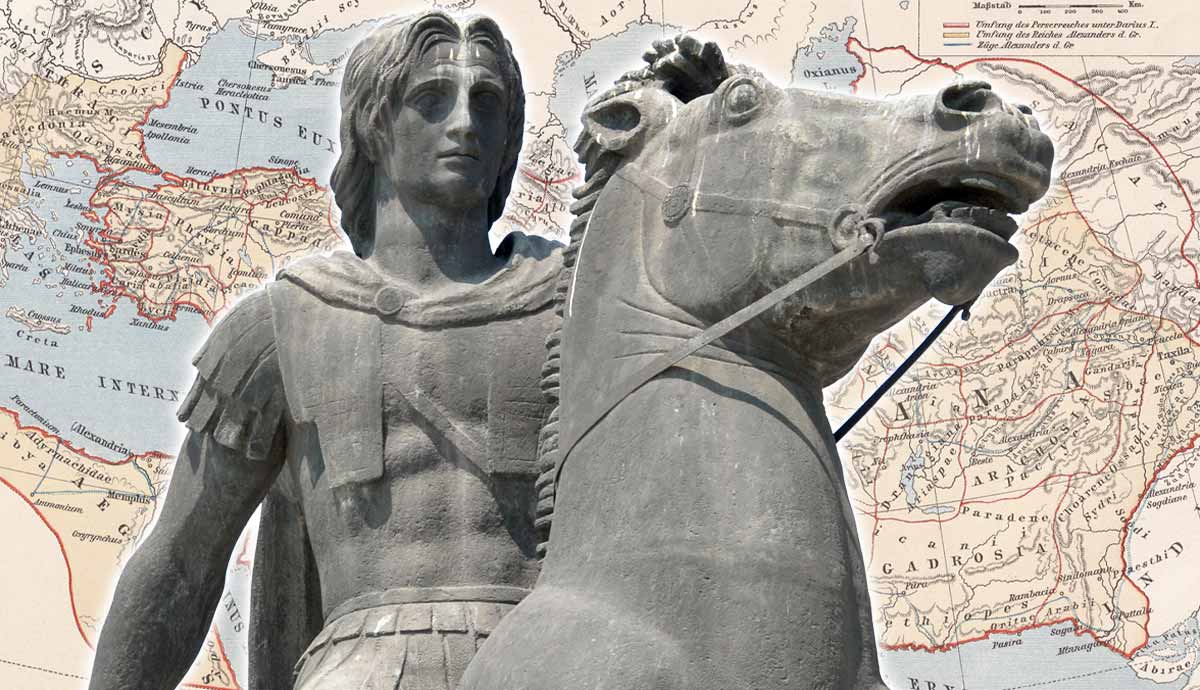

Following the mutiny of his army, Alexander the Great was forced to abandon his eastward march. In response, he turned his attention towards defining the borders of his new territory in India. Marching down the Hydaspes and Acesines rivers, he was opposed by the Malli and Oxydraci, two powerful tribes. In response, Alexander launched a lightning campaign against both tribes, during which he rapidly overran both of their territories. However, during the final siege of the campaign, against the capital city of the Malli, his impetuousness nearly led to his death.

Down the Rivers

Having crossed the Hindu Kush and defeated King Porus in battle, Alexander the Great continued to lead his army northeast along the Ganges River. At the Beas River, the Macedonians mutinied and refused to go any further. They had suffered great casualties fighting Porus. The Nanda Empire, which they were approaching, was said to be even more powerful. Many of the men had been away from home for years, and while they had grown rich, they were also no longer young. There was a desire to see their families again and enjoy their wealth and status. To make matters worse, it had been raining for some 70 days, so conditions were miserable. It was a tense situation. Eventually, Alexander gave in and turned the army to the south.

Alexander’s plan was to follow the Hydaspes River to the sea and, from there, march back home. As he prepared to head out, the army linked up with a sizable column of reinforcements that brought with it much-needed supplies. This greatly boosted the men’s morale ahead of the march. It was a good thing, as Alexander did not envision a peaceful trek. An important component of his plan was to define the eastern border of his new empire. The Hydaspes River was a major geographical feature. This made it the perfect border for Alexander’s empire. All he needed to do was to make sure that everyone within and along the new border recognized that he was their king.

The Mallians and Oxydracians

At first, the Macedonians experienced only slight resistance, which is what they expected. Most Indian cities, tribes, and states had heard of Alexander’s earlier victories and did not feel strong enough to challenge him. As such, progress was relatively quick, with the army and a fleet moving directly along the river, and only on occasion moving slightly inland. However, not everyone was willing to allow the Macedonians to pass through their territory so easily. Alexander and his generals soon received word of a worrying development further downstream ahead of the army. A pair of powerful Indian tribes had formed an alliance and were preparing to block the Macedonian advance.

These tribes were the Malli and Oxydraci, who lived around the confluence of the Hydaspes, Acesines, and Hydraotis rivers. Today these rivers are known as the Jhelum, Chenab, and Ravi rivers, and the capital of the Mallians is the modern city of Multan. Since the names given for these tribes are from Greek sources, we do not know a lot about who they were. There is some speculation, however, that the Malli migrated to modern Rajasthan and became the Malavas. Regardless, the Malli and Oxydraci were a formidable force. They had been enemies in the past, but apparently felt the need to put aside their differences to face the Macedonians. According to the reports Alexander received, they could field 90,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 900 chariots.

Preparing the Way

While the Malli and Oxydraci were strong when united, individually, each tribe was far weaker. For this reason, Alexander’s goal was to prevent them from joining forces. The Macedonians were willing and able to wage war year-round, which was unusual during this period. In Greece, warfare usually paused during the winter, while in India, wars were not waged during the rainy or cold season. As it was late in the year, the Malli and Oxydraci expected Alexander to go into winter quarters. They believed that they had plenty of time to prepare for the coming war. They were mistaken. As soon as he received word of the alliance, Alexander sped his forces down the river.

The journey down the river was a dangerous one, and many ships sustained damage along the way. However, the Macedonians managed to arrive at their destination. Immediately, they set up camps on either side of the Hydaspes at the confluence with the Acesines to secure their lines of communication. Alexander then turned his attention to the nearby Sibea tribe, which, while hostile, had not fully joined into the alliance with the Malli and Oxydraci. The Sibea could field an estimated 40,000 warriors and were positioned in such a way that they could potentially threaten the Macedonian camps and lines of communication. Alexander, therefore, struck without mercy. The capital of the Sibea was taken and burned along with all their crops while all the men were slain and the women enslaved. Alexander intended to send a message to the Indians who would resist him.

A Macedonian Blitz

Alexander was determined to prevent the Malli and Oxydraci from escaping. He therefore launched a series of carefully coordinated marches. First, he sent a force down both banks of the Acesines to the point where it joined the Hydraotis, which also happened to be downriver from the Malli capital city. Here, they established a camp from which they could prevent the Malli from escaping while supporting Alexander’s operations. Meanwhile, Alexander crossed the Acesines and marched through the desert towards the Hydraotis. The Malli were taken by surprise by this action and driven southwards. A second force followed three days behind Alexander to capture and slaughter anyone who managed to escape.

With this sudden onset, the alliance between the Malli and Oxydraci essentially collapsed. They could not decide on who should lead them or what to do, so they retreated into their strongholds for safety. Having now reached the city of Kot Kamalia, Alexander again split his forces. One force crossed the Hyrdraotis to the north, while Alexander crossed at a point much further downriver. The first force then pushed south towards Alexander, driving all before it. The Macedonians were once again proving themselves to be masters of siege warfare. Their torsion catapults were particularly effective at breaching walls. At the modern Brahmin town of Atari, the Malli realized that they could not defend the walls and retreated into the citadel. In response, Alexander set fire to the citadel, and 5,000 Malli are said to have perished in the blaze.

Sweeping Up Resistance

By this point, Malli resistance outside of their capital had basically ceased. Nonetheless, Alexander sent out two of his generals to sweep the forests, deserts, and swamps in search of refugees. All those who attempted to resist were put to the sword. The Malli had, in the meantime, gathered the rest of their forces to defend their capital, possibly the modern city of Multan. When the Macedonians approached, the Malli drew up their forces on the far bank of the Hydraotis to offer battle. However, Alexander realized that his men had become an object of fear to the Malli. This was part of his motivation for waging such a brutal campaign. Alexander, therefore, immediately ordered his men to charge across the river.

When faced with the charging Macedonians, the Malli fled almost immediately. The Macedonian cavalry, which led the charge, began its pursuit, which stretched on for over 5 miles. Eventually, the Malli realized that they were only being pursued by the Macedonian cavalry. The Macedonian infantry had not been able to join in the initial charge and, as a result, lagged far behind. It is estimated that there were around 50,000 Malli warriors, while the Macedonian cavalry numbered only a few thousand. Alexander was, however, undaunted by this sudden reversal and continued to lead from the front. The Macedonian cavalry relied heavily on its superior speed and mobility to strike at the Malli warriors while preventing them from striking a decisive blow. When the Macedonian infantry began to arrive, the Malli lost heart and fled back to their city.

The Siege of Mallia

After resting his men, Alexander began his siege of the Malli capital city. Since the city was located on an island in the Hydraotis, the Macedonians had to approach it with care. The Malli immediately retreated into their fortifications when the Macedonians approached. These fortifications were very substantial and had a circuit nearly a mile long. However, the gates were apparently weak or perhaps improperly secured. This allowed the Macedonians to gain entrance, and they quickly overran the outer defenses. In response, the Malli retreated within the inner layer of defenses and continued to resist. So, Alexander now sent his men forward to begin undermining these walls, by tunneling under them until they collapsed.

The progress of the Macedonian siege to this point was rapid and perhaps uneven. Alexander had begun the siege by dividing his army into two columns to surround the city. This was done to ensure that no one would escape and to threaten multiple points at once so that the defenders could not concentrate in one spot. However, it did make communication and coordination more difficult for the columns. If the Malli had not been suffering from such low morale, they could have potentially sallied out and defeated the Macedonians in a piecemeal fashion. As it turned out, the greatest danger came not from the Malli, but from Alexander’s own impatience.

Alexander Falls

While Alexander the Great may have been a man of many virtues, one of them was not patience. The speed at which his men had already overrun the other cities of the Malli and Oxydraci likely encouraged him to believe that this city would fall just as quickly. It was a nearly fatal mistake. According to ancient historians, Alexander became impatient with the speed of the siege. This is interesting as he had been part of many much longer sieges, during which it had taken weeks, if not months, to reach a position comparable to the one he found himself in now. Some have suggested that it was not the speed of the siege that so irked Alexander, but rather the efforts of his men, who may have been slacking.

Whatever the case may have been, Alexander decided on bold action. Grabbing onto one of the siege ladders, he ascended the walls. The rest of the Macedonians, realizing what was happening, attempted to follow, but the ladders collapsed under their weight. Only two soldiers were able to join Alexander on the walls. When the Malli realized who Alexander was, they strove to kill him. The Macedonians called out to Alexander, begging him to jump off the walls into their arms. However, when Alexander leaped from the wall, he leaped down into the inner courtyard and not into the arms of his soldiers. In the courtyard, Alexander and his two soldiers were set upon by the Malli. Alexander managed to kill a Malli chieftain but was hit in the lung by an arrow, causing him to fall to the ground.

Aftermath

The Macedonians reacted to Alexander’s leap by going into a frenzy. With their bare hands, they scaled the walls and battered down the gates. Reaching Alexander, they swiftly bore him away on a shield. The inhabitants of the city were then slaughtered mercilessly by the Macedonians. Rumor spread like wildfire that Alexander had been killed. However, back in the camp, the arrow was removed by an emergency surgical procedure. Alexander’s life remained in jeopardy. For at least four days, he hovered between life and death. Eventually, he had to be brought out and presented to the army to prove that he was still alive despite his condition in order to quell the unrest.

As Alexander recovered, he was confronted by his generals and closest companions, who demanded he never risk himself again in such a way. He also officially received the surrender of the surviving Malli and Oxydraci. The way was now clear for Alexander and the Macedonians to continue on their march downriver to the sea. There would be a few minor battles along the way, but nothing as spectacular as the Mallian campaign. The campaign was a strategic masterpiece in almost all respects. While Alexander’s personal prowess and bravery are certainly to be admired, his rashness cost him and the army dearly. Today, the siege is more remembered as an example of Alexander’s willingness to take risks, his impatience, and his tendency for rashness than for anything else.