Widely recognized as the “father of psychoanalysis,” Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud forever altered the way we see ourselves. Believing our adult behavior is driven by repressed childhood experiences of love, loss, sexuality, and death, he wrote extensively on the subject as well as practicing psychoanalytical therapy with many patients in distress. Nowadays, most of Freud’s ideas have generally been replaced by a more rational, scientific approach to human psychology. However, within the arts, the creativity and inventiveness of Sigmund Freud’s theories continue to fascinate and inspire countless creative thinkers.

Sigmund Freud’s Role In The Arts

Freud’s involvement with the arts during his lifetime included several strands of activity. He wrote extensively about the lives and personalities of artists, particularly those from the Renaissance. Freud was also an avid art collector. Throughout his life, he amassed a vast archive of over 2,500 antiquities from various ancient civilizations. Such was the extent of his collection that his London home was converted into the Freud Museum in 1986 to showcase his impressive archive to the world.

Although Freud’s personal preference was for ancient art, his psychoanalytical theories had a lasting influence on the early 20th-century avant-garde. As artists moved increasingly beyond the visible world into explorations of the individual human mind, Freud’s theories encapsulated the spirit of the times, and his techniques of dream analysis and free association had a particularly profound impact on the international Surrealist movement. Even today, artists continue to find fertile source material in Freud’s fascinating theories, while his grandson, Lucian Freud, is one of the 21st century’s most popular painters.

Sigmund Freud’s Writings on Art

Freud was fascinated by art. Dissecting the minds of creative thinkers became an important strand of his practice as a writer, allowing him to search for the deeper drives that compelled these creative geniuses. He wrote analytical essays on individual artworks, including The Moses of Michelangelo. He even published an entire book on Leonardo da Vinci, titled Leonardo Da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood, 1910, exploring the artist’s childhood, sexuality, and how it came to inform his art as an adult. Although Freud was sometimes criticized for bringing too much autobiographical content into his art essays, the way he intrinsically linked artists’ lives with their work has undoubtedly shaped the way we understand art today.

Another fascinating theory Freud developed around art was his concept of “ideational mimetics.” He argued an artwork could cause a powerful exchange of energy between the viewer and the work of art, similar to the experience of empathy. Freud argued this experience was a fundamental part of life in higher-level civilization, revealing how important he saw the role of art in society.

An Astonishing Art Collection

In 1986, Freud’s London home was converted into an art museum, showcasing to the world the extent of his vast art collection. One hundred years earlier, in 1896, the young Freud was still living in Vienna, while his father had just passed away. During this period of dramatic upheaval and re-evaluation, he began collecting art objects. Still relatively unknown and with a limited income, Freud’s earliest purchases were plaster replicas of Italian Renaissance artworks. However, as his career flourished in the years that followed, Freud’s collection became increasingly diverse and adventurous. He developed a particular taste for rare antiquities, seeing in ancient civilizations intrinsic meanings about human society, which in turn came to inform much of his writing and theories. Many of his art objects were bought from Vienna’s markets, originating from ancient kingdoms around the world, including Egypt, Greece, Rome, India, China, and Etruria.

Freud displayed the collection in his Vienna office and later in London when forced to run from Nazis during the Second World War. On the walls, they were arranged in an eclectic, haphazard way, as Bryony Davies, assistant curator at the Freud Museum points out: “Freud’s own display style was personal … his objects appear in his own unique way.” On his desk, he had his smallest and most precious objects laid out, which he enjoyed touching or even carrying around with him while he was working, while cabinets were packed with objects arranged into groupings including Greek vessels and Eros statues. Freud had a particular fascination with two faced figures, which feature prominently in his collection, and reflect his theories on dualisms, such as pleasure/reality, life/death, and conscious/subconscious.

Freud’s statuette of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war, was one of his most prized possessions, which he would sit on the center of his writing desk. A copy of a Greek original, Freud’s version most likely dates from the 1st or 2nd century A.D. Freud smuggled Athena with him when he fled from Austria to London following the Nazi invasions of the Second World War, and she still sits proudly on the desk of his London Museum today.

Sigmund Freud’s Impact on Surrealism

Freud’s theories had a particularly profound impact on the Surrealist Movement of the early 20th century. They, in turn, brought his ideas into the public eye, making him more popular than ever. His iconic text, The Interpretation of Dreams, 1899, was particularly important to Surrealist artists. Connecting with Freud’s belief that dreams could reveal hidden meanings about our innermost desires, which were often erotic or sexualized, the Surrealists discovered and pioneered a wide range of techniques, unleashing the wondrously complex, unconscious world of dreams into their art.

Many Surrealists adopted Freud’s techniques of free association and automatic drawing, working in a way that they believed could release unconscious thoughts. These included automatic writing without forethought or drawing and painting with free-flowing, improvised methods, as seen in the freewheeling line drawings of Paul Klee and Joan Miro. Max Ernst also made rubbings, scrapings, and collages that relied on chance, play, and accident. Collage was a popular technique that allowed artists to work quickly, combining images from clashing sources in strange and unexpected ways. French poet Andre Breton, who led the Parisian Surrealist group, called these ideas “Thought expressed in the absence of any control exerted by reason, and outside all moral and aesthetic considerations.” These ideas, in turn, shaped the intuitive art of the American Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s, including Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock.

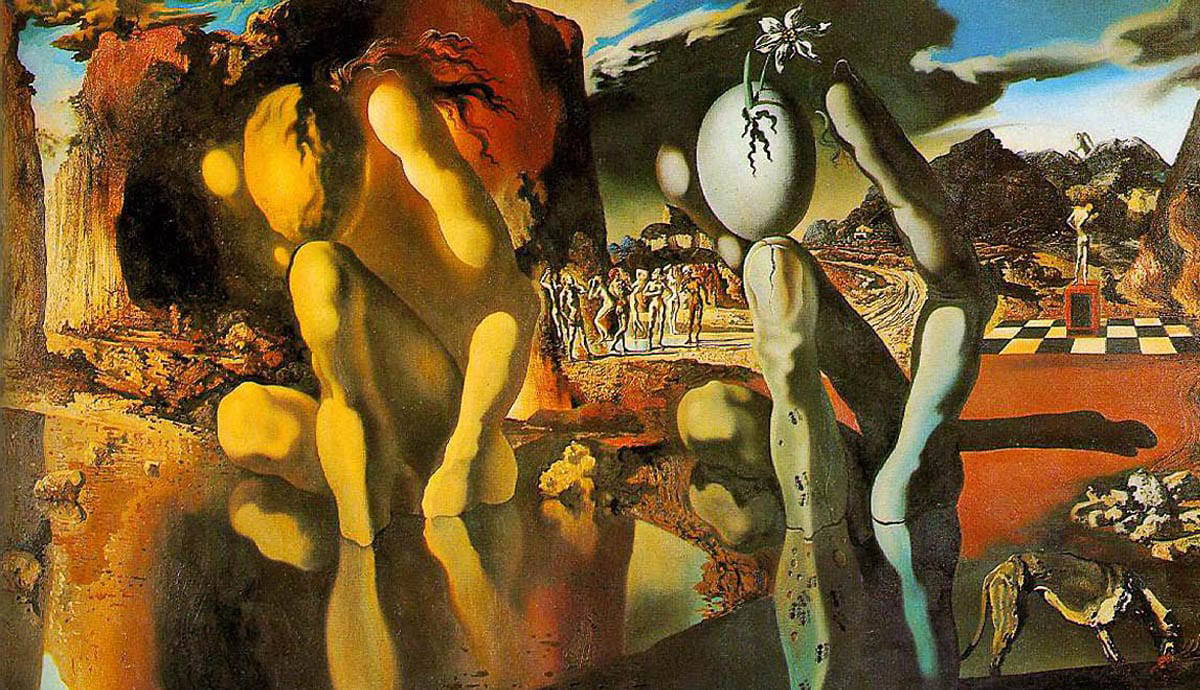

Some Surrealists took inspiration from their own dreams and nightmares to invoke a Freudian world, creating startlingly life-like depictions of a strange, alternate reality. In Dorothea Tanning’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, 1943, a domestic scene turns into a horrific nightmare, while in Salvador Dali’s strange, mystical landscapes, objects are stretched, distorted, and turned into monstrous beings. Dali claimed his imagery came from his visionary dreams, which he would see just as he was falling asleep, calling this phase “the slumber with a key.”

Freud’s essay on The Uncanny, published in 1919, also had a lasting impact on Surrealist art. Freud argued that “the uncanny” was a translation of something once familiar into the haunting and disturbing, making it strangely familiar, such as eerie dolls coming to life, doppelgangers, or mirrors and shadows. These theories have proved immensely popular with artists working in a wide range of media, including sculpture, photography, and film. In the wake of the First World War, Freud’s theories on the uncanny had particularly jarring resonance with many because the once ordinary and familiar had been transformed into the fearful and menacing. Hans Bellmer’s haunting dolls took on this uncanny quality, as did Man Ray’s transformation of a flat iron into a weapon in Cadeau, 1921.

Freud was said to be somewhat bemused and baffled when, as he wrote, “the Surrealists have apparently chosen me as their patron saint.” Unimpressed by much of their art, he argued their attempts to create the illusion of automatic thought and dream-like imagery were too self-conscious and driven by ego to be convincing.

Sigmund Freud’s Theories And Its Influence In Art Today

The Surrealists did much to popularize Freud’s theories in the modern and contemporary art world. One of the most prominent artists to follow on their legacy was the French sculptor Louise Bourgeois. She argued the best art of the 20th century had a confessional, autobiographical element and was “a form of psychoanalysis.” Citing her own troubled childhood as the inspiration for much of her art, she regularly underwent psychoanalysis four times a week for most of her adult life. Her artworks are brimming with sexual innuendo and make reference to Freud’s theories on gender, particularly his belief that we have both male and female aspects to our identity. Janus Fleuri, 1968, has a two-part, hybrid sexuality, and the horrifyingly graphic The Destruction of the Father, 1974, envisions her destroying her father in a truly Freudian scenario.

Many of the Young British Artists in the 1990s played with Freud’s theories, particularly the British sculptor Sarah Lucas. Reimagining Freud’s concept of the uncanny with a cheeky, laddish slant, her famous installation, Au Naturel, 1994, transforms seemingly banal, found objects into an arrangement loaded with crude sexual references. Other works draw on the lewd sexual languages of Hans Bellmer and Louise Bourgeois, made from stuffed tights filled with foam, which become lumpy or dangling mutations resembling both male and female body parts.

Alongside Freud’s own extensive art collection, The Freud Museum stages regular solo and group displays, as well as commissioning site-specific projects, which reveal the psychoanalyst’s long-lasting influence on contemporary art practices. To celebrate 100 years since the publication of The Uncanny, in 2019, the Freud Museum staged The Uncanny: A Centenary, featuring artworks by Hans Bellmer alongside contemporary practitioners, including Elizabeth Dearnley, Martha Todd, and Karolina Urbaniak; this display revealed how Freud’s endlessly recyclable theories continue to ignite sparks of inspiration in the next generation.

FAQs

How are contemporary artists building upon Freud’s legacy, and what new perspectives are they bringing to his theories?

Contemporary artists build on Freud’s legacy by exploring the unconscious, identity, and desire through modern lenses like gender, trauma, and technology. They challenge or reinterpret his ideas, addressing issues Freud overlooked. By blending his focus on the psyche with current cultural themes, they make his theories relevant to today’s artistic and social conversations.

What specific objections were raised against Freud’s approach to art criticism, and how did he respond to these criticisms?

Critics argued that his psychoanalytic interpretations oversimplified complex works. Freud responded by emphasizing the importance of understanding underlying psychological motivations in art but acknowledged that his interpretations were just one layer of meaning among others.

How have Freud’s theories influenced art movements other than Surrealism, such as Abstract Expressionism or Pop Art?

Freud’s theories, particularly on the unconscious, influenced Abstract Expressionism by inspiring artists like Jackson Pollock to explore spontaneous, subconscious expression. In Pop Art, Freud’s ideas on desire and identity shaped works that examined consumerism and mass media’s influence on personal and cultural psyche, as seen in Warhol’s exploration of fame and repetition.