Portugal holds one of the oldest borders in Europe. However, several people populated the region long before the Zamora Treaty officially recognized the Portuguese Kingdom in 1143. Iberian tribes and the Celts were the first. Next came the Roman Empire and the Visigoths. However, it was the Moorish who stayed the longest. Their presence left deep marks in Portuguese culture, especially in Silves. Some are still visible today in language, architecture, and culinary traditions.

Xelb, the Arab Prodigy of the Gharb Al-Andalus

Silves is an ancient city dating back to the Iron Age, where Phoenicians and Romans lived before the Moorish conquered the city in 716. Xelb, as it became known, was a wealthy city in the Gharb Al-Andalus (the southwestern region of the Iberian Peninsula). Surrounded by fertile agricultural fields and located 15 kilometers (9 miles) from the coastline, Silves was only accessible by boat through the Arade River. As a result, trading with other cities in Al-Andalus was fairly safe.

To strengthen their occupation, the Moors allowed both Christians and Jews to stay and continue with their daily lives as long as they abided by Moorish laws. Since the Visigoths tormented the Jews with forced baptisms or exile, this felt like a breath of fresh air.

As a result, Xelb enjoyed a long period of prosperity and peace. Over the years, the city grew to hold 30,000 people from all over Northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Eventually, the city flourished and became an economic and cultural mecca, also known as a city of philosophers and poets. It is often compared to other magnificent cities such as Lisbon, Seville, and Cordoba.

Due to Xelb’s political and economic influence, it was declared the Taifa of Silves. The city was the capital of an independent Arab kingdom, ruling the westernmost region of the current Algarve.

Silves After the “Reconquista”

As the Moorish enjoyed economic prosperity in the south, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, Count Afonso Henriques of Condado Portucalense had one goal: to expel the Moors and claim their territory.

After winning the Ourique Battle against the Moors, Afonso Henriques was proclaimed the first King of Portugal in 1143. During his lifetime, he also conquered Coimbra, Santarém, and Lisbon. His descendants followed in his footsteps and continued pushing the Moors further south.

D. Sancho I, son of D. Afonso Henriques, was the first king to try conquering Silves. Due to the city’s strategic importance, D. Sancho believed if he overthrew the city, others in the region would follow. Yet, he did not have enough men or weapons to face the Moors. As a result, he hired Northern European crusaders headed to the Holy Land and promised them the payment in the form of looting Silves’ riches.

After a long siege, the Moorish finally surrendered. The Crusaders looted the city and disregarded the king’s orders by killing anyone standing in their way. Silves was almost deserted after the battle. The survivors fled to Seville and Granada, leaving only a few Christian soldiers and farmers behind.

The Moors reconquered the city a few years later, but the Silves lacked its former splendor. In 1249, the Christian armies conquered the city again in another bloody battle. King D. Afonso III ordered the resettlement of Silves and named it the capital of the Algarve Kingdom. Nevertheless, Silves’ economy declined as people settled in the coastal areas, and lived in fear of another battle.

Silves’ Historical Heritage

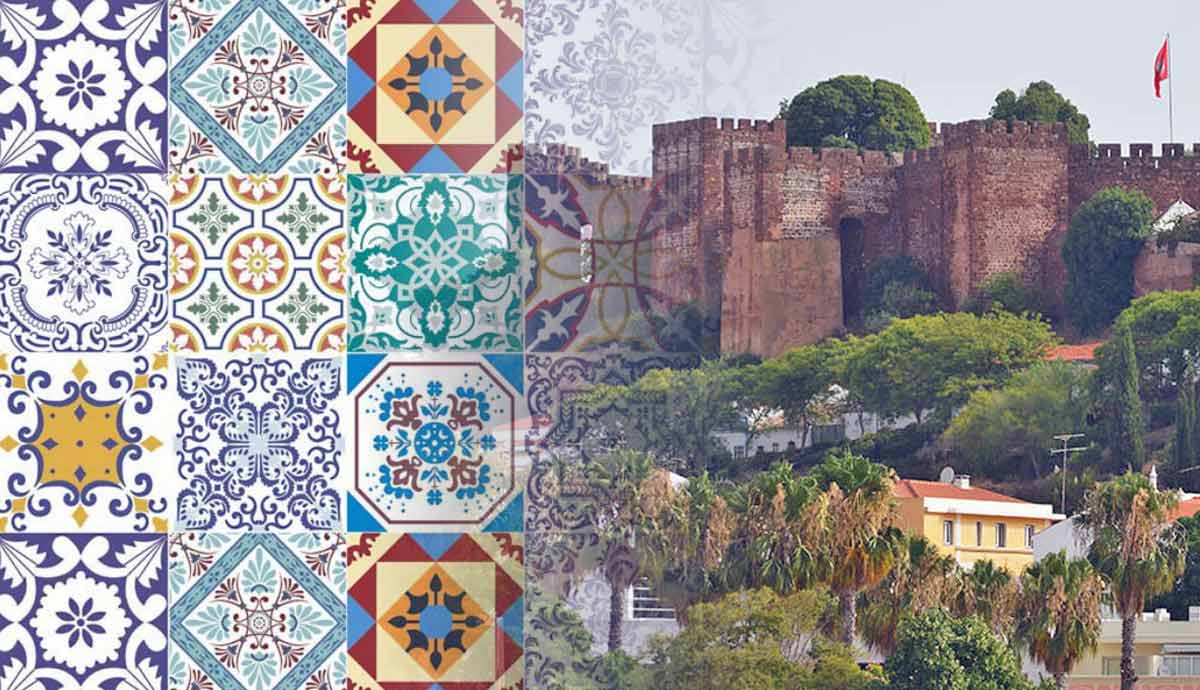

While roaming Silves’ streets, you will find traces of the city’s past anywhere you look. The labyrinthic narrow-cobbled alleys, white-washed houses, rooftop terraces, indoor gardens, and façades covered in geometric-shaped “azulejos” (tiles) are some of the Moorish influences still visible today. The Moors also introduced the Algarve’s most well-known fruits: orange, almond, carob, and figs. The region’s warm and sunny weather created the perfect conditions for these fruits to thrive.

Even the word “Algarve” comes from the Arabic “Al-Gharb,” and according to the Portuguese writer Adalberto Alves, there are more than 19,000 Portuguese words of Arabic origin. Silves hides many intriguing facts, and every corner veils a piece of history.

The Impressive Red-Walled Castle

Once you arrive in Silves, you will feel drawn to the imposing castle on top of the hill and its surrounding walls. Although history books tell us the Moors built the castle, the truth is that they repurposed an existing Roman fortress. Covering more than 12,000 meters square (approx. 13,0000 feet), the castle and its walls were built with “taipa,” a mixture of clay, pebbles, sand, and local sandstone, which is responsible for its distinctive red tone.

The Islamic fortification organized the city into two different areas: the “alcáçova” (from the Arabic “al-kasbah”) and the “medina.” The alcáçova refers to a large area on top of the hill, inside the castle walls, protected by eleven towers. Here, you can admire the Moura cistern, the largest in the alcáçova, which supplied Silves until the early 1990s. Today, the city council converted the cistern into an exhibition room. A few steps away, you will find the cistern of the Dogs.

Together, these cisterns collected and stored rainwater, supplying the alcáçova and the medina all year round. Inside the alcáçova, you will also find the archeological remains of the Palace of Balconies. This palace fortress had an area of 320 meters square (1050 feet), two floors, and plenty of rooms, patios, indoor gardens, and baths. According to archaeologists, this is the only Islamic palace in Portugal. Here, you can admire the recreation of the palace’s Islamic broken arches and imagine how luxurious this building once was.

Surrounded by outer walls, the medina was a mixture of white-washed houses and labyrinthic narrow streets, which you will notice while roaming the streets. Over the centuries, Silves Castle was rebuilt several times, on one hand, due to the violent battles, but also due to several earthquakes that hit the region. Nevertheless, Silves’ Castle is a unique example of Islamic military architecture in Portugal.

Exploring the City Gate

Originally, Silves had three city gates: Porta da Almedina, Porta do Sol, and Porta da Azóia. Nowadays, only Porta da Almedina still stands, known as Torreão das Portas da Cidade. It is a sandstone albarrana tower, which provided access from the alcáçova to the medina and the city mosque. While walking through it, you will notice the narrow curve designed to make access difficult. More recently, the Portas da Cidade accommodated the city council, the local police, and the library. Today, it is one of the city’s landmarks.

Silves Municipal Archaeology Museum

At a short distance from Portas da Cidade, you will find Silves Municipal Archaeological Museum. It contains an extensive archaeological collection recovered from excavations in and around Silves, dating back to prehistoric times, through to the Iron Age, and the Roman occupation. Yet, most of the artifacts on display come from the Islamic occupation.

The central piece in the museum is a 12th-century Almohad cistern-well. Built with the local red sandstone, the cistern well has a mouth 3 meters in diameter (10 feet) and is connected to phreatic waters at 18 meters deep (59 feet). The water level at the bottom of the well is visible all year round. A vaulted spiral staircase with three windows and roofed by a segmented tunnel vault allows access to the well’s depth, besides providing ventilation and natural light.

This incredible monument is located close to the wall surrounding the medina. Because of this, archeologists believe the cistern-well’s purpose was to supply the lower parts of the city, including the public baths 100 meters away (328 feet). Once the Christians conquered Silves, the cistern-well was abandoned and filled with rubbish. It was only rediscovered in 1979 when the city council was doing reconstruction work in the area.

Besides this incredible monument, archeologists found a variety of ceramics dating between the 3rd and 17th centuries. You can admire all these items at the museum.

Silves’ Cathedral

Although Silves was named the seat of a bishopric in 1189, the cathedral construction began only in 1268 when the Christians conquered the city. The pristine white-washed façade contrasting with the lively red sandstone offers a striking view. It is no wonder it is one of the most visited monuments in the Algarve.

The original Gothic style was altered many times due to reconstruction and restoration works over the centuries. Here, you can admire the Rococo and Manuelino architectural styles on the temple’s façade. Inside, you will find Gothic ogival vaults and Baroque side altars. Nevertheless, Silves Cathedral is the best example of Gothic architecture in the Algarve.

Even though archaeologists are still looking for unequivocal evidence, they believe the cathedral was built over an old mosque. They have already found the remains of a cistern under the cathedral and worn stones in the tower bell which has led archaeologists to believe these are much older than other stones in the same area.

The Roman Bridge

The bridge’s origins remain a mystery to this day. The locals call it “Ponte Romana” (the Roman Bridge). However, the bridge, as we see it today, was built in the 15th century. According to the latest investigations, there is no evidence that the bridge was a piece of repurposed infrastructure. Besides, the Islamic descriptions of Silves never mention a bridge. The first reference dates back to 1439, when the population complained to the king about a bridge damaged by floods. In the following years, the bridge was rebuilt.

Built with red sandstone blocks, Silves’ Roman Bridge is 76 meters long (250 feet) and 5 meters (16 feet) wide. The iconic five-round arches supporting the bridge’s deck are interspersed with triple-sided pyramidal carvings, with side railings and a belvedere.

The Roman Bridge was the main access to the Western Algarve, until the 1960s when it showed signs of structural damage. As a result, the city council built a new bridge and converted the old one into a pedestrian pathway.