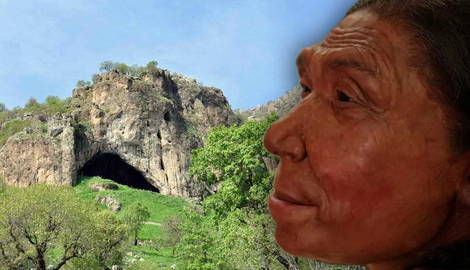

Located in the Zagros mountains in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq, Shanidar Cave served as an important place for Neanderthals for tens (possibly even hundreds) of thousands of years.

The discoveries made there have upended our beliefs about the Neanderthals. No longer confined to pure speculation, the secrets of the skeletons of Shanidar have changed the way we look at our evolutionary cousins and the way we see ourselves.

Who and What Were the Neanderthals?

Regarded as the “other us,” Neanderthals occupy a divergent space on the human evolutionary tree. While they were making their home in the Middle East and the icy regions of Europe, Homo sapiens evolved in Africa.

The two species evolved separately, with differing lifestyles and vastly contrasting demands. Homo sapiens did not, however, stay in Africa forever. Migrating beyond the confines of the continent, they spread into Europe and Asia, finally coming into contact with a branch of humanity that had been on a different evolutionary path for hundreds of thousands of years.

The two species of human beings met around 100,000 years ago (possibly more). They recognized the obvious physical differences but also their similarities, as genetic evidence proves that they interbred. Given the evolutionary distance between these two species, it is surprising that they were compatible, yet it certainly happened. Of course, compatibility wasn’t assured. Most of the offspring would likely have been infertile. Yet certain individuals (perhaps only female hybrids) were viable and continued the lineage.

This is how modern Homo sapiens ended up with Neanderthal DNA. All human beings today have up to 4% Neanderthal DNA.

Compared with modern Homo sapiens, Neanderthals were shorter and stockier. They were built for toughness rather than long distance-running as Homa sapiens were. Marked differences in skull shapes show that Neanderthals had heavy brow-ridging and bigger noses, among other features that were different from Homo sapiens. Of all the species on the human evolutionary tree, Neanderthals had the biggest brains. This, however, does not necessarily mean they were more intelligent. Debates over their mental capabilities are ongoing, but it is generally accepted that their levels of intelligence were similar to ours.

How our archaic ancestors perceived them is a subject of speculation. We know very little about the cultures that existed during the Stone Age and have little idea of how people treated their own kind, let alone how they treated those who were different. Theories range from genocide to peaceful coexistence and intermingling.

The discoveries of Shanidar do, however, give us insight into how the Neanderthals treated their own.

Shanidar Cave: Discovery and Excavation

Because of its location and the obvious advantages that such a cave might have had, Shanidar Cave presented itself as a prime example of prehistoric archeology. American anthropologist Ralph Solecki, who excavated the site in the 1950s, made the first study of Shanidar Cave.

Four seasons of excavations yielded the remains of seven Neanderthal adults and two Neanderthal children. The specimens date from 65,000 to 35,000 years ago, occupying a fairly wide period in prehistory.

Recent excavations have also yielded more discoveries. In 2018, the remains of another Neanderthal were found, dating back over 70,000 years.

Shanidar 1: Extensive Injuries

One of the most intriguing individuals is that of an adult male who stood 5 feet 7 inches tall. Shanidar 1 suffered terrible injuries during his life. The left side of his head had received a terrible blow, causing injuries that may have blinded him in the left eye and damage to the part of the brain that controlled the right side of the body. His right arm was withered, and his right leg was crippled. His right foot had also been fractured at some point.

None of these injuries killed him outright. He died between 35 and 40 years of age, which, for a Neanderthal, would have been considered old. All his injuries show signs of healing. There is no way this would have been achieved without the care of those around him. Shanidar 1 therefore spent much of his life being looked after.

The implications of this discovery were exceedingly important in that they upturned the common belief that Neanderthals were thuggish brutes. Shanidar 1 is evidence that Neanderthals cared for each other and had the skills to look after grievous injuries. This suggests a level of compassion thought to only exist in our own species.

Shanidar 2

Shanidar 2 was a Neanderthal male who stood 5 feet 2 inches tall, suffered from slight arthritis, and died around the age of 30. He was killed 60,000 to 45,000 years ago after being crushed by falling rocks.

Stones sharpened to points were found on top of this grave, and nearby was evidence of a large fire. These suggest some sort of funerary ceremony.

What is also interesting about the remains of Shanidar 2 is that the skull had a higher cranial vault than typical Neanderthal skulls and was more representative of a Homo sapien’s skull in this particular aspect. The relevance of this is debated. It has been suggested that the particular group of Neanderthals was very diverse and that the similarity between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens is closer than previously thought.

Shanidar 3: Interpersonal Violence

The remains of Shanidar 3 are fragmentary, and this fact led the specimen to receive little initial attention compared with some of the other discoveries. The lack of a skull also meant it was far more difficult to glean information about this individual.

The remains of Shanidar 3 indicate sharp force trauma to the left ninth rib, possibly from a spear tip or something similar. The bone shows signs of several weeks of healing, which indicates that Shanidar 3 did not die immediately from these wounds. It is also possible that these wounds had little to do with Shanidar 3’s death. The bones were also crushed by a cave-in, which may have been the cause of death. This may have also happened after Shanidar 3 had already died.

Forensic evidence suggests the wound was not self-inflicted. Thus, Shanidar 3 remains the oldest evidence of interpersonal violence.

Shanidar 4: “The Flower Burial”

Shanidar 4 was an adult male who died around the age of 35 to 40. He was positioned on his left side in a fetal position and was discovered in 1960. Eight years after his discovery, the soil around him was analyzed, and large clumps of pollen were discovered.

The implications of this discovery set imaginations off. It was suggested that flowers were placed by his grave in a ceremonial display. Moreover, the pollen was connected to several species of flowering plants that exhibit healing properties, fueling a theory that the individual performed the function of a shaman and that the flowers were symbolic of his ability to heal people.

More recent theories suggest that the pollen was deposited by burrowing rodents rather than any action linked to human sentiment.

Whatever the truth may be, the debate still attracts much attention.

Shanidar 5

Caught in the same rockfall that killed Shanidar 2, Shanidar 5 was a male aged between 40 and 50 years when he died. Despite the remains being fractured and scattered, archeologists were able to determine that Shanidar 5 was a particularly robust individual.

In 2015 and 2016, ongoing archeological digs at Shanidar uncovered more fragments from Shanidar 5.

A five-millimeter-long scar on the frontal bone of the cranium, along with the evidence of bone trauma on the other skeletons, adds weight to the theories that the Neanderthals lived incredibly tough lives fraught with danger.

Shanidar 6, 7, 8, & 9

Shanidar 6 was an adult female who was likely between 20 and 30 years old when she died. The remains found were mostly fragments of the limbs, and along with Shanidar 8 and Shanidar 9, were found beneath Shanidar 4.

Shanidar 7 and 9 were infants. Shanidar 7 was approximately six to nine months old at the time of death. Shanidar 9 was six to 12 months old, and only a few of the upper vertebrae have been found.

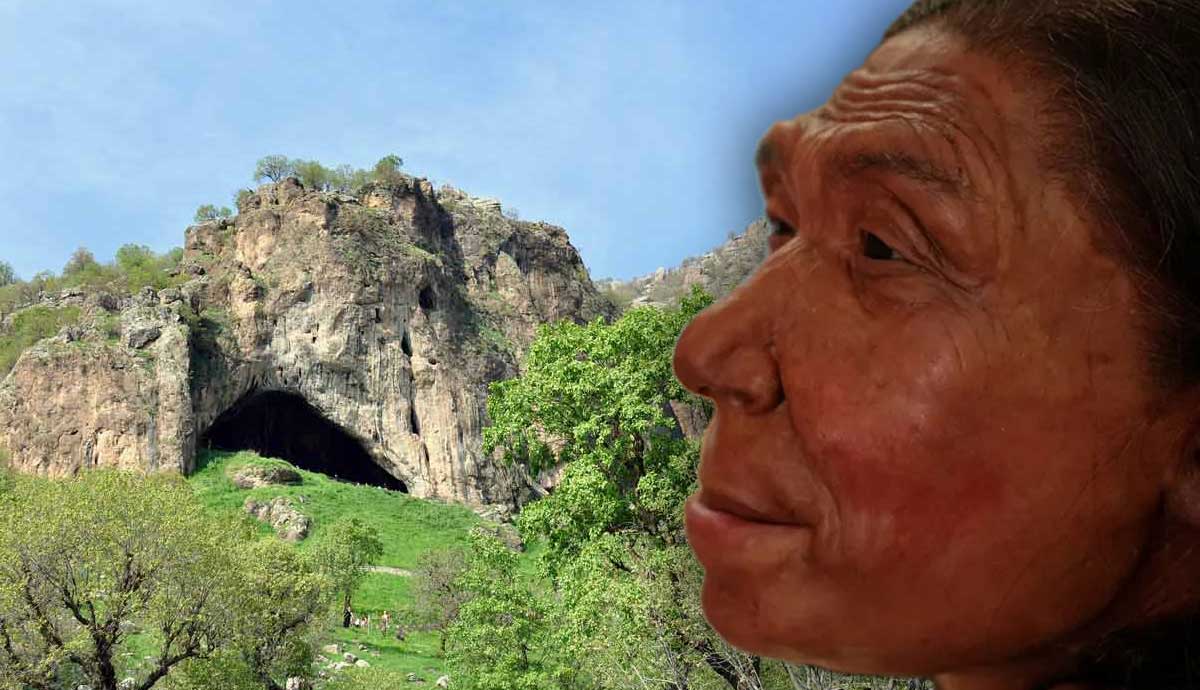

Shanidar Z

The discovery of Shanidar Z in 2018 came as a surprise to Professor Graeme Barker and his team, who currently lead the excavations at Shanidar. Shanidar Z lived around 75,000 years ago and died in her mid-to-late 40s. She stood around five feet tall.

Like some of the other specimens, care was taken when she was laid to rest. Her arm and hand were placed under her head and it seems a rock was placed behind her head as a pillow.

The remains had been severely crushed after death, and more than 200 fragments of the skull lay in a layer less than an inch thick. Years of painstaking cleaning and reassembly resulted in archeologists being able not just to piece the skull back together but to create a bust of what Shanidar Z actually looked like. When the skull had been reconstructed, it was scanned, and a 3D model was printed and sent to Dutch paleoartists Adrie and Alfons Kennis, who used their considerable talents to show us what Shanidar Z looked like.

The astounding reveal was captured in the documentary Secrets of the Neanderthals, released on Netflix in 2024.

The discoveries from Shanidar Cave have changed the way we see humanity in terms of both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. They have provoked a deeper introspection of our place in the world and what it means to be human, bringing us much closer to the part of our evolutionary family tree that left us too soon.