Despite its relative obscurity compared to other cinema powerhouses like France, Germany, and Japan, the South American film industry has a storied history all its own. Though Brazil and Argentina claim the top spots for film production on the continent, other countries, including Chile and Colombia, are starting to make inroads in the industry as well. The ten South American films highlighted here explore complex themes, including redemption, grief, and marginalization, while showcasing the region’s culture, landscapes, music, and visual arts—and its tumultuous political history.

1. Black Orpheus (Brazil, 1959)

Frenchman Marcel Camus’s take on the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, Black Orpheus, made history. For starters, it was the first of only four films to win both the Cannes Film Festival’s Palme d’Or and Best Foreign Film in the Academy Awards. It was also the first internationally acclaimed movie filmed entirely within a favela, as well as the first to feature an almost entirely Afro-Brazilian cast.

Black Orpheus features tram conductor Orfeu dancing his way through the Brazilian festival Carnival with Eurydice, a country girl on the run from a man in a skeleton costume. It’s an incredible feast for the senses, full of technicolor visuals, intricate costuming, and expressive, spirited dance routines. It also has a wildly catchy samba soundtrack composed by world-renowned bossa nova pioneers Luiz Bonfá and Antonio Carlos Jobim.

The film’s portrayal of Afro-Brazilian life has been celebrated by some and criticized by others. It makes more of an attempt at anthropological realism—for example, by including a Candomblé ritual in the climactic scene—than the 1956 play it is based on. But critics argue that Black Orpheus still paints an overly romantic picture of favela life.

Viewers should make up their own minds, though—because regardless of which side wins out, Black Orpheus is certainly worth the watch.

2. City of God (Brazil, 2003)

For a more cynical—and perhaps more realistic—take on Rio’s favelas, check out City of God. An adaptation of Paulo Lins’s semi-autobiographical novel of the same name, City of God tells the story of Rocket, a young boy fighting to escape from the slums. His way out? A camera. But in a Sontag-esque twist, Rocket’s search for the perfect shot, to win fame and freedom, draws him deeper and deeper into the endemic violence of the favela.

There’s a rich and fascinating historical context to City of God. Set in Cidade de Deus, a 1960s-era housing development/resettlement project intended to relocate Rio’s slums from the city center to its outskirts, City of God probes the social factors that feed crime and poverty in Brazil. An unflinching portrayal of violence and extreme social marginalization, it forces viewers to face the collective rage, resentment, and cynicism bred by Rio’s built-in class divide.

More than that, though, City of God features inventive editing, sharp humor, and stellar acting from a non-professional cast hired straight out of the favelas. It’s no wonder the fast-paced gang thriller was a box office hit around the world—and an award-season favorite, too. It received a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film and was nominated for four Academy Awards.

3. Liverpool (Argentina, 2008)

There’s very little dialogue or drama in Liverpool.

This fact may seem surprising, considering the plot of the film—a seaman has returned home to remote Tierra del Fuego following twenty years away to visit his mother, who may or may not still be alive. The premise seems loaded with potential for emotional outbursts.

Instead, Lisandro Alonso takes a minimalist angle, quietly following sailor Farrell’s journey home and his attempts to reconnect with his family. Instead of fights or fanfare, Farrell finds himself isolated and half-forgotten—a feeling that proves far heavier than hatred.

It’s not for everyone or every mood. But for those who revel in barebones, contemplative storytelling, Alonso’s ability to craft an intimate psychological portrait through the use of action, environment, and physicality is on full display in Liverpool.

4. Jauja (Argentina, 2014)

Another Lisandro Alonso feature, Jauja takes a turn from the personal to a much grander scope: human history, mythology, desert, and sea.

The film, set in the 1880s, follows Captain Dinesen, a Danish engineer traveling through Patagonia with his teenage daughter, Ingeborg, and a company of soldiers. Their task, set by the Argentine government, is to exterminate the local indigenous people.

However, when Ingeborg elopes with one of the soldiers, Dinesen’s relentless search for her leads him into the barren desert—and a surreal, mind-bending journey through the depths of human history and mythology.

The title of the film is an allusion to La Tierra de Jauja, a mythological land of plenty (much like El Dorado). However, as the film’s epigraph proclaims, European settlers’ search for Jauja was doomed from the start: “The only thing that is known for certain is that all who tried to find this earthly paradise got lost on the way.”

Alonso’s Jauja is about loss—lost daughters, lost cultures, lost paradises. But more than that, it’s an exploration of Argentina’s roots, from the mythic and psychological to the material and historical.

5. Nostalgia for the Light (Chile, 2010)

For a less expressionistic dive into Latin American history, check out Nostalgia for the Light—a documentary focused on Chile’s Atacama Desert. The expanse of the Atacama ties together three separate threads of history. Thousands of years ago, Chile’s indigenous people created artworks that are still remarkably well preserved due to the Atacama’s dry climate. More recently, the Augusto Pinochet regime constructed concentration camps for political prisoners—and buried the dead in shallow graves in the Atacama’s sands. Today, astronomers take advantage of the desert’s altitude and cloudless skies—and, as the documentary suggests, astronomy is also a kind of history.

Nostalgia for the Light parallels the physical landscape of the desert—and the traces of human history left behind—with the expanse of the night sky. Interviewees range from astronomers searching for extraterrestrial life to volunteers, mostly women, who have spent years scouring the desert for the remains of their loved ones. It all points toward something very essentially human: the desire for meaning, continuity, and connection.

6. No (Chile, 2012)

Another take on the Pinochet regime, No tells the mostly-true story of an advertising campaign to vote the dictator out of power.

In 1988, finding himself under growing international pressure—and confident in the support of Chile’s middle and upper class—Pinochet permitted a referendum on whether he should be allowed another eight years in office. The protagonist of No, marketing consultant René Saavedra, finds himself tasked with creating 15-minute nightly TV spots to convince Chileans to vote “no” on Pinochet.

Initially, leftist campaigners (including René’s estranged wife) had focused their advertising on the human rights abuses of the Pinochet regime. However, politically ambivalent René convinces them to take a different angle: saccharine platitudes, rainbows, unicorns, and dancing children—all pointing toward a brighter, happier future.

On its face, No is an inspirational film about replacing fear with hope—and helplessness with action. But beneath the surface, there are some much more cynical implications: what does it mean to advertise the choice between dictatorship and democracy in the same way corporations might advertise the choice between Coke and Pepsi?

And, more darkly, No’s anticlimactic conclusion reminds us that winning the vote wasn’t the same as winning Chile’s freedom or escaping its past. As director Pablo Larrain explained in an interview with IndieWire, “It’s still an open wound. We never had justice. The people who actually were the killers, we have a few in jail, but most of them are walking free in the street. Pinochet died free, a millionaire.”

7. La Ciénaga (Argentina, 2001)

La Ciénaga is the story of two Argentine women: Mecha, a bourgeois mother who vacations with her family each year at their summer house in the jungle, and Tali, her working-class friend who lives in the nearby town of La Ciénaga.

Both have absentee husbands: Mecha’s is an alcoholic, and Tali’s works constant overtime. Both feel trapped in their lifestyles, forced to mirror those of their respective husbands. While Tali works herself to death, Mecha drinks her life away—and the summer house crumbles, slowly being reclaimed by the swamps that surround it.

La Ciénaga can be difficult to follow at times. There are many plotlines, many characters, and many relationships. But it all reinforces the film’s theme of wasted time and unproductive pursuits. Getting too attached to any one thread is like getting stuck in a swamp: a struggle against the inevitable.

Despite the lack of clear direction, though, director Lucrecia Martel’s brilliant use of color, sound, and small, physical details makes La Ciénaga a brilliant adventure through the jungles of decadence and desire.

8. The Club (Chile, 2015)

On the outskirts of a Chilean beach town, four former Catholic priests—each guilty of his own sins, from baby-snatching to whistleblowing—live in isolation under the close supervision of a retired nun. However, they find their search for penance interrupted when a new member joins their quiet community: a pedophile.

Following the arrival of Sandokan, one of his now-adult victims, the priest commits suicide. Not long after, Padre García, a counselor intent on shutting down church-sponsored sanctuaries like the one featured in The Club, arrives to assess the situation. Sandokan and Padre García alike prove to be subversive additions to the community, challenging the members of “the club” to reconsider their understanding of their own crimes—and of their penance.

The Club interrogates the clemency granted to disgraced priests by the Catholic church. Director Pablo Larraín asks what it means to live in tranquility and whether exclusion is truly the path to redemption. Perhaps, he suggests, it would be better to find a way forward through plurality.

9. The Official Story (Argentina, 1985)

Historical drama The Official Story marked the re-emergence of Argentina’s film industry after the collapse of the 1976-1983 dictatorship and a series of military governments that prevented the flourishing of a vibrant arts scene.

The film centers around Alicia, a history teacher and member of the Argentine political class, who has begun to question the origins of her adopted daughter, Gaby. As its title might suggest, The Official Story is based on a real, devastating history. Following the 1976 coup, children of leftists were routinely taken from their parents and given to childless and well-connected supporters of the military regime. Gaby is one such child.

In addition to exploring the brutal history of neoliberal policy in Argentina, The Official Story presents a complex but beautiful portrait of motherhood. Despite her reluctance to confront the facts of Gaby’s adoption (and her own infertility), Alicia’s love for her daughter drives her to greater and greater lengths to uncover the truth.

The Official Story does such an impeccable job of intertwining the personal with the political that it is, perhaps, no wonder that it was so well received on the domestic and international stage.

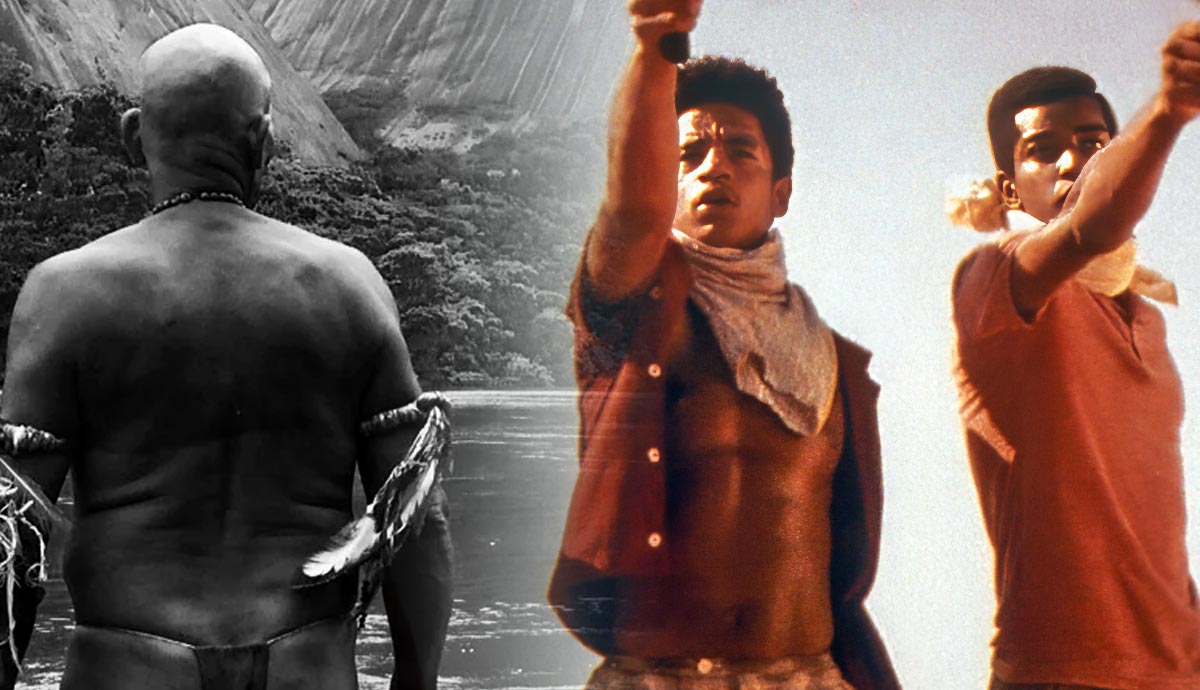

10. Embrace of the Serpent (Colombia, 2015)

Last, but certainly not least, is Embrace of the Serpent, a multigenerational epic centered around Karamakate, an indigenous Amazonian shaman and the sole survivor of his tribe.

The first act of the story takes place in 1909, when a young and impassioned Karamakate meets German anthropologist Theo von Martius and agrees to guide him up the Amazon River. Both Karamakate and Theo have their own selfish motives: Karamakate wants to search for other members of his rapidly vanishing tribe in unfamiliar lands, and Theo wants to find yakruna, a sacred plant that he believes will cure his fatal illness.

But before Theo and Karamakate’s journey is finished, Embrace of the Serpent jumps 30 years into the future, to Karamakate’s meeting with a new outsider: American botanist Evan, dispatched by the US government to locate a source of healthy rubber trees.

Karamakate has become a chullachaqui—an empty shell, out of touch with the ways of his people. But he agrees to help Evan search for yakruna once again, so that they might heal the spiritual sickness of modernity.

Director Ciro Guerra conducted meticulous research for the film. He read the expedition diaries of European ethnologists and biologists, spoke with Amazonian indigenous peoples, and even learned their languages. Thanks to this rich historical context, Embrace of the Serpent is able to portray the pillaging of the Amazonian landscape—and the degradation of indigenous practice, belief, and humanity—by European explorers with a truly unique level of sensitivity and complexity.

Guerra’s words on the film—and the value of Latin American cinema—said it best:

“Young people, when they see this film, think maybe their culture is important after all… And it is, I think. Not only for them, but for us. Especially for a country like Colombia. This culture and what it can give to the world is our biggest asset as a country, more than mining our natural resources.”