The architectural movement of Brutalism has British roots, yet it reached its full potential in the Soviet Union behind the Iron Curtain. This architectural style emerged from the post-war necessity to rebuild destroyed cities in an affordable, easy-to-build way. Soviet Brutalist buildings, still standing tall in now independent countries, were bold and ambitious projects that had their unique features related to ideology, regional and national traditions, and climate conditions. Here are 9 remarkable examples of Soviet Brutalism in its intimidating glory.

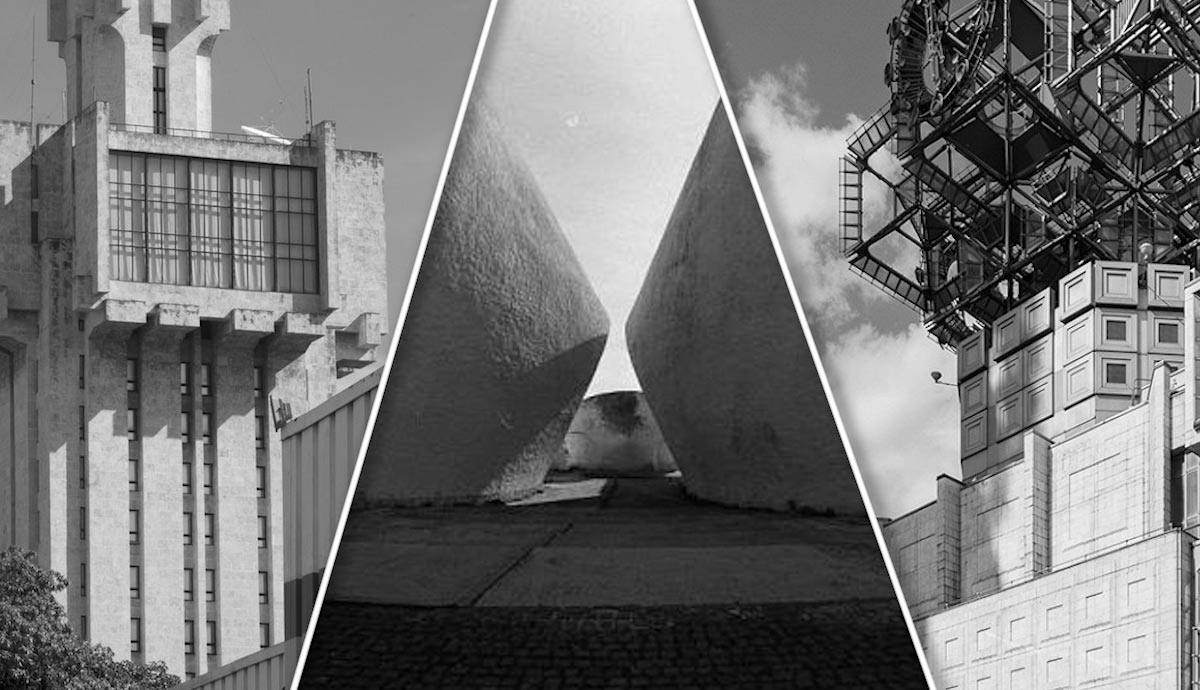

1. Bank of Georgia in the Style of Soviet Brutalism

The classic example of Brutalist architecture—the closest in its nature to European and American representatives—is located in Georgia. It’s currently operating as the headquarters of the main bank of the country. Constructed as a central office of the Georgian Ministry of Highway Construction, it bore a striking resemblance to the iconic Canadian Habitat 67, a residential complex made from several hundred pre-made concrete blocks.

The leading architect, George Chakhava, was also the Deputy Minister of Highway Construction, so he had a chance to tailor the project to his needs and standards. Chakhava found great inspiration in the works of El Lissitzky and Russian Constructivists. His idea was to occupy as little ground as possible, so the building unfolds on its top floors that look like branches on a tree that are supported by a trunk.

2. Kyiv Crematorium, Kyiv, Ukraine

The complex of Kyiv Crematorium consists of two concrete shells facing each other, with spaces dedicated to grieving relatives inside. The functional structures and mechanisms were hidden underground to turn the visitors’ attention away from the physical aspects of cremation and burial. Designed in the late 1960s, it was specifically made to avoid direct associations with incineration of bodies, still fresh and painful after the Nazi massacres in Ukraine.

The history of this unusual building started with a monument called Wall of Memory which was constructed as part of the memorial complex. The reliefs on the wall represented stages of human life and connection to one’s native land. However, in 1982, soon after its completion, the wall was cordoned off and covered in concrete which covered the reliefs. As explained by the Soviet authorities, they deemed the style too expressive and contradictory to the official ideology. Uncovering and restoring the Wall of Memory was one of the first decisions made by the independent Ukrainian state after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

3. House of Nuclear Atomists, Moscow, Russia

This long residential building in the southern part of Moscow was a long-term experimental project that offered almost a thousand apartments to its residents. Today, it is still active, but it lost its appeal due to its enormous size.

Among the Moscow locals, the building quickly became known as the Ship-House due to its resemblance to a cruise liner. It was also known as the Bachelors’ House due to the number of unmarried engineers who lived in one-bedroom apartments. Another nickname the building received was House of Nuclear Atomists, but it was not because they settled in the new building. The leading architect, Vladimir Babad, had never worked with residential complexes before, but he did have tremendous experience constructing nuclear reactors. His expertise allowed the Ship-House to become extra-resistant to seismic activity. It could even, allegedly, survive bombings and nuclear explosions.

4. Chisinau Circus, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

The brutalist building of Chisinau State Circus was built to mark the 545th anniversary of the city’s first mention in historical sources. The architects decorated the facade with sculptures of clowns and acrobats. The interior featured colorful mosaics referencing early Soviet avant-garde art. The project illustrated the flexibility of Brutalist architecture, easily incorporating decoration and detail that were in contrast to the raw and minimalist aesthetic of the concrete structures.

Chisinau Circus was abandoned for decades. The building even started slowly collapsing and sculptural clowns lost their heads due to corrosion. However, in recent years, the Moldovan government announced plans to restore the building and protect it as an important piece of cultural heritage.

5. Academy of Sciences Headquarters, Moscow, Russia

The legendary and controversial example of Soviet Brutalism, the Academy of Sciences headquarters was a long-awaited project that was particularly hard to realize. The building was designed in the 1960s, but the construction work was being constantly delayed as the architects faced obstacles at almost every stage. During the three decades of planning and construction, the Soviet Union collapsed, so the building changed its context and purpose almost overnight.

Unable to live and work in political turmoil and uncertainty, many Russian scientists moved abroad instead of settling in the newly constructed headquarters. Some superstitious locals claimed that it was the cursed land that was forcing people to leave—according to a legend, the location was occupied by slaughterhouses and the ground was soaked with blood.

The building’s structure remains a mystery even to those who work there. Some say that the metallic structures on the top hide some special service facilities. No one can say for sure how many underground floors there are and how people can access them. There are also hundreds of elevators hidden throughout the complex.

6. Aul Residential Complex, Almaty, Kazakhstan

The round towers of the residential complex in Kazakhstan were among the boldest and the most ambitious parts of the Soviet residential experiments. Aul got its name from a specific type of fortified stone-built villages found in Central Asia and the Caucasus region. Circular forms created softly curved pathways, allowing for more natural movement of residents.

The key to understanding Aul’s puzzling design lies in observing the harsh climate conditions of the region. The rounded balconies were designed to limit the heat and light that came inside the apartments. The seismic activity in Almaty is exceptionally high, requiring additional support and safety measures for all tall buildings. Each tower consists of three round structures that support each other and redistribute weight.

7. Sevan Lake Union of Writers’ House, Lake Sevan, Armenia

The round concrete structure facing the Armenian Lake Sevan was built decades before the term Brutalism was coined, yet it still fits into the category. In 1932, the building functioned as a resort and a working area for the members of the Soviet Writers’ Union. The curved glass terrace allowed for a wider view of the lake with spaces made for outdoor leisure right below it.

The astonishing building hides a tragic story of repressions and terror. In 1937, its architects, Kochar and Mazmanyan, were arrested and deported to polar regions of Russia. The two were accused of nationalism and supporting Leon Trotsky. They were rehabilitated and returned to Armenia after Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953. Today, the building functions as a small and run-down hotel, but it maintains its astonishing view of the lake. In 2016, the Getty Foundation partially financed the much-needed renovation, but the futurist-looking terrace is still far from its former glory.

8. Russian Embassy Building, Havana, Cuba

The complex of the Soviet embassy in Cuba with its intimidating tower was simultaneously a nod to Constructivist architecture and a gesture of dominance in the region. Small windows and thick concrete function as protection from heat and light while also adding the psychological effect of the stable presence of the Soviets. Some locals compared the building to a sword that’s plunged into the ground, while others thought it resembled a medical syringe. The tower’s construction started during the Cold War and it remains an austere reminder of the dark past, starkly contrasting with other countries’ embassies located nearby.

9. Soviet Brutalism With a Twist: Uzbekistan’s State Museum of History

The state museum in Tashkent is one of the most significant examples of seemingly international and depersonalized Brutalist style bending under the influence of local traditions and customs. It was originally built as a museum dedicated to Vladimir Lenin. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, it changed its focus to the history of Uzbekistan and Central Asia. Although technically a part of the Soviet Brutalism legacy, it looks unusually decorative.

The decorations, however, have distinct functions. One of the main goals of Uzbekistani architecture was to limit the harsh sunlight, especially in places like museums, where sunshine could do much harm. Carved panels covering the facades are not merely decorative but protective as well, ensuring the museum space is shielded from harsh climate conditions. At the same time, the ornament inspired by local crafts makes the building visually lighter while also hinting at the building’s current purpose.