Before cinema and television became the norm, the circus was a popular entertainment form worldwide. During the Russian Revolution and Stalin eras, art, circus comedy, and expression in Soviet public spaces walked a tightrope between conformity and dissent. A political joke told to the wrong person at the wrong time could land someone in the Gulag, the vast Soviet forced labor camp system. During the twentieth century, two Polish clowns, known by their stage name Bim-Bom, risked their lives to entertain a nation and satirize the Soviet state.

The Circus in Prerevolutionary Russia

In the 20th century, Russia became a synonym for circus. During the post-Stalin thaw, Soviet performers toured Europe and the United States. These global tours made the Moscow Circus famous outside the Soviet Union.

The roots of the circus in Russia and Ukraine are almost 1,000 years old. In the 11th century, wandering comedians, minstrels, and jesters called skomorokhi appeared as echoes of ancient, pagan Slavic folk culture. They performed songs, comedies, and conjuring tricks in villages and squares for weddings, feast days, and spring or winter solstice celebrations. Skomorokhi also appeared at open-air sporting events such as horse races and bear fights.

During the sixteenth century, the skomorokhi began to unite and travel in groups of 60 to 100 people. Skomorokhi wore bright clothing, caps with jingling caps, leather masks, or animal horns. They sang folk songs, told ribald jokes, engaged in political satire, and told comic stories in rhyme that attracted crowds to their shows and away from the church.

Like Bim-Bom’s act hundreds of years later, these jesters used buffoonery and political satire to expose the day’s big and small social problems. They poked fun at the weaknesses of the common people and the foibles of the merchants, boyars, clergy, and other influential people.

The wandering minstrels’ irreverent popularity turned the elite against them. Banning popular art was nothing new. Since medieval Rus’, the tsars and the Orthodox Church censored folk culture that involved tricks, jokes, puppets, and song-and-dance acts regarded as “demonic” or a threat to the state.

Some tsars did not appreciate the skomorokhi lifestyle or habit of poking fun at the rich and powerful. In 1648, Tsar Alexis I, the second Romanov ruler, waged war against the skomorokhi, banned their profession, and burned their balalaikas. Accused of witchcraft and sinister intentions, artists suffered corporal punishments, hard labor, or exile. Many skomorokhi, storytellers, balalaika artists, and gusli players escaped to Ukraine. There, itinerate folk bards called kobzars rose during the Cossack Hetmanate in the seventeenth century.

The circus experienced a resurgence under Peter I. Peter the Great loved the circus and brought it back into circulation. Circus performers appeared in court again. Show booths sprang up at village fairs, town squares, and other public celebrations. While the skomorokhi disappeared, their comedic legacy survived in popular memory, lingered in folk sayings, and evolved into modern circus acts.

From Streets to Stages

Over the next two hundred years, street entertainment with a knack for popular songs, storytelling, tumbling acts, and satirizing authority evolved into a new entertainment form for the aristocracy.

In the early nineteenth century, stationary, indoor circuses began to appear. Even Tsar Nicholas I helped design circus sets. After the abolition of serfdom, the circus began to thrive with new input from peasant artists. In 1877, during the reign of Tsar Liberator Alexander II, an Italian horseman named Gaetano Ciniselli, a legend throughout Europe for his bold performances, opened an opulent circus in St. Petersburg. Housed in an ornate building on the Fontanka Embankment, the Ciniselli Circus featured a lavish royal box, a grand stage, and programs printed on silk in French and Russian. The building held 1,500 seats, and shows sold out a year in advance.

In 1880, Albert Salamonsky opened the first Moscow circus in a stone building on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. It became the first circus that performed children’s shows, New Year’s tree displays, and Christmas plays. Since they typically functioned without stage directors, the popularity of these circuses depended on their artists’ high level of creative art. Until 1919, no state circuses, only private circuses, existed. By the 1890s, over 50 circuses and circus show-booths operated across the Russian Empire.

The Bim-Bom Act Is Born

The Bim-Bom circus act started with Ivan Semyonovich Radunsky. Born in Poland in 1872, Radunsky found his way into popular entertainment after his stepfather kicked him out at age 16. He found his way to Odesa in Ukraine and began performing in the streets. Later, he played pots and bottles on a stage in the garden at the Odesa Brewery (Stites, 1992, p. 19).

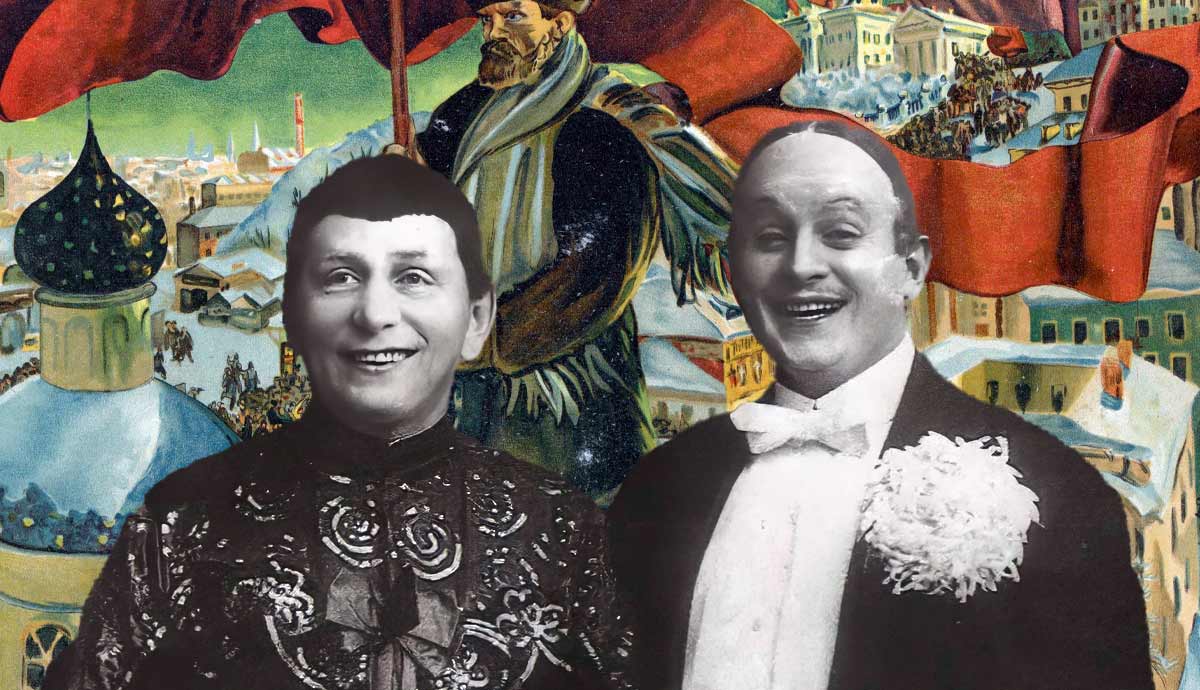

In 1891, Radunsky moved to St. Petersburg, where he joined a Russian-Italian musician named Vitaly Lazarenko Cortesi (Miller, 1999, p. 190). They took the stage name Bim-Bom. Together, they created a new clown duo act. Radunsky penned witty lyrics, and Cortesi wrote the music. They wore white clown makeup and knee-length costumes made from silk with puffy sleeves and lace collars. Cortesi also wore a black nose and a red wig. Their act took off after Bim-Bom performed at the popular Ciniselli Circus (Leach and Borovsky, 1999, p. 127).

In 1897, Cortesi died in a drowning accident while swimming in a river while on tour in Astrakhan. After Cortesi’s death, Radunsky struggled to keep the act going. First, he tried to act with his wife, then with Cortesi’s wife. But none of these stand-ins rivaled the satirical hilarity he managed with his first performing partner. Three years later, Radunsky found a new partner named Mieszyslaw Antonovich Stanievsky.

Like Radunsky, Stanievsky started his circus career in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Born in Poland, Stanievsky worked as a carpet clown in provincial circuses. A carpet clown appeared between the main act while workers switched the set and carpets. They performed various tricks and acrobatics and delivered verbal routines. Stanievsky capitalized on these skills when he joined forces with Radunsky in 1900.

A Dynamic Duo

The new Bim-Bom partnership became the stars of the Ciniselli Circus. Their act began with a song-and-dance routine trotted out by Bim. Bom followed with hard-hitting lines. Bim assumed a naïve and eager persona. In contrast, Bom delivered witty and scathing ripostes as a slightly drunk man about town. While Radunsky often wore a clown costume, Stanievsky disdained a clown aesthetic. Instead, he sported a giant chrysanthemum on his tuxedo.

According to some sources, Radunsky joined the Bolshevik Party before the Russian Revolution. He also aligned himself with the Futurist movement. Futurism thrived in Russia between 1910 and 1917. It rejected sentimental and bourgeois art forms in favor of art that reflected the working class. The Futurist movement focused on the relentless pace and dynamism of machines, industry, and active urban hustle. The Futurists broke away from static art forms to promote a dynamic and modern vision of the future.

During the Russo-Japanese War, the duo dropped their slapstick and acrobatic routines to focus on musical comedy and topical satire. While government censorship often banned their reprises, satirical jabs at military incompetence and government repression still slipped through:

Bim: “Do you know, Bom, there aren’t enough machine guns in the Far East?”

Bom: “I know.”

Bim: “And how do you explain this?”

Bom: “Why give them to strangers? They can be useful against our own.”

Radunsky and Stanievsky performed this act until the government banned it. Then, they went off on a grand tour around the empire.

Despite censorship bans, Bim-Bom’s career flourished. After Salamonsky died, his circus crumbled. In 1914, the circus performers elected Radunsky as the director of the Salamonsky Circus. Radunsky had no previous managerial experience, but under his leadership, the circus flourished again.

During the First World War, he organized the Russian Society of Variety and Circus Artists (ROAVTSA). Together, Radunsky and Stanievsky also took part in patriotic performances during World War I (Hubertus, 1998, p. 94).

Meanwhile, Bom ran a bustling artistic café named BOM on Tverskoy Boulevard. From 1916 to 1919, the café brimmed with Social Revolutionaries, Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, and artists such as the Chekist Yakov Blumkin, internationalist Yuliy Martov, the author Ilya Ehrenberg, and the clown Vladimir Durov. The café closed during the Russian Civil War (Evdokimova et al. 2021, p. 24).

Thanks to the invention of the gramophone, Bim-Bom had the chance to immortalize their lines with a record company. Konona Records produced their first record, Tangled Kinship. Sirena-Grand-Record released Bim-Bom’s next album, Scena Komiczna. Zonophone Record released Hunting Adventure, a comic dialogue in 1910. These record companies released vast quantities of Bim-Bom records and shipped them nationwide before government censors could stop them. Across the country, fans snapped up Bim-Bom records and played them in defiance of the ban.

Bim-Bom became a famous cultural icon, appearing in several early films and receiving a notable mention in the 1956 Soviet movie Carnival Night.

Nationalization of the Circus

After the October Revolution, the Soviet government nationalized the circus in 1919. They also launched mass theater-circus displays as a new propaganda platform. Bolshevik festivals became all the rage among soldiers, sailors, and workers in urban areas (Rolf, 2013, p. 99).

From ballet and theater to circus performances, performing arts in early Soviet Russia had a dual purpose. They functioned both as a popular art form and a platform for propaganda. Vladimir Lenin believed that the circus had real potential as a tool for mass propaganda. In response, Soviet artists such as Vladimir Mayakovsky composed political lines and propaganda circus plays ridiculing relics of the recent past, such as religion, tsarism, capitalism, and various perceived enemies.

The Soviet circus fell under a specialized agency, first known as the Circus Central Management and later as SoyuzGosTsirk (the Union of State Circuses). Their first symbolic act was to demolish the old, aristocratic Salamonsky circus building and build a new modern circus on the spot. The Soviets renamed the Salamonsky and Nikitin circuses the First and Second State Circuses (Neirick, 2012, p. 33).

The government decreed state-sponsored productions, and Anatoly Lunacharsky, a Bolshevik critic, playwright, and commissar for the Ministry of Education, carried out the reforms.

The former Salamonsky Circus became a famous space to prime audiences for propaganda. Despite their political goals, the Soviet Committee for the Arts did not have a clear goal for the medium of circus art. Instead, they dabbled in an art form they did not fully grasp. Now, the propagandists ran the show. Konstantin Stanislavsky launched an experimental, politically correct circus spectacle called Political Carrousel. It was a spectacular flop. After this sensational failure, the Bolsheviks turned the circus over to a professional manager.

While the new director, William Truzzi, put the circus back on track, so many artists had fled that the circus’ quality remained low. Too few artists remained to run multiple permanent circuses. While the Soviets kept pushing artists to use the circus as a propaganda vehicle, things did not always go according to plan.

The Hottest Act in Moscow

Disillusioned with the Soviets, Radunsky and Stanievsky pitted their wits against the new power. Their popularity soared. In 1918, the Bolsheviks still found themselves on shaky political ground. They influenced but did not yet fully control circus repertoires.

Bim and Bom spiced up their routine by decorating and playing unusual musical instruments such as brooms, saws, pans, flowerpots, music stands, business cards, and bottles. They remembered their lines using a cheat sheet with the verses written on the back of each instrument and even on the wide cuffs of their sleeves (Leach, 1994, p. 5).

During one performance, Bim stepped onto the stage between two framed pictures of Lenin and Trotsky. Glancing at the leaders of the October Revolution, Bom asked Bim what he planned to do with them. Radunsky didn’t mince words:

“I’ll hang one and put the other against the wall.”

This innocent remark had darker connotations that amounted to “black laughter” or hangman’s humor. In December 1917, the Bolsheviks established the headquarters of the Cheka, or Soviet secret police, at Number 11 Bolshaya Lubyanka Street in Moscow. The Cheka began its first executions in the building’s basement just two months later. Later, the Cheka set up local stations throughout the country to conduct mass terror. Bim-Bom’s remark reflected Bolshevik propaganda that vowed to put their enemies “against the wall” to execute them (Seldes, 1995, p. 198-200).

Having a reputation as the hottest act in Moscow came with its risks. Unfortunately, the Cheka did not share their sense of humor. They soon saw Bim-Bom’s counterrevolutionary laughter as a threat (Terbish, 2022, p. 30).

On March 27, 1918, Bim-Bom gave their most memorable performance. As usual, the two clowns ignited the arena with flashes of satire.

Bim: “In French – le savon,”

Bom: “And in Russian – soap.”

“The French – sorry,”

“But the Russians – in the snout.”

“In French, it’s a promenade,”

“But in ours, it’s a jail cell.”

“The French have liberté,”

“And we have the whip.”

“In French, an amateur –”

“But in ours – an amateur.”

“The French have a quartermaster –”

“And we have a robber.”

Sitting in the audience, Cheka agents and members of the Bolshevik Latvian Riflemen did not find it funny. Right in the middle of the performance, the secret police pulled out their revolvers and rushed the stage to arrest the clowns on the spot. The audience laughed, thinking it was part of the act. When Radunsky spotted the Cheka’s Browning revolvers, he bolted backstage. The secret police shot after him and missed, hitting several people in the audience (Figes, 1997, 631). Panic erupted inside the circus. In the chaos, Stanievsky hid in the circus stables. Miraculously, they escaped.

The next day, the Cheka hauled the pair in for questioning. Radunsky and Stanievsky still wore their circus costumes. With Soviet power only established for a few months and an anti-Bolshevik Army rising south of Moscow, the Bolsheviks preferred to avoid a popular protest. They let the clowns go with a warning (Kotkin, 2015, p. 287).

Censored Satire

After an attempted Soviet land grab and Polish resistance, the Russo-Polish War ended with an uneasy ceasefire in 1920. That year, Stanievsky returned to his homeland to run a circus with his brother. Radunsky joined him in 1925, and they performed in Poland for several years. They also recorded a new album with Sirena-Records.

In 1925, Radunsky returned to the USSR and resurrected the comedic duet with a new partner,

Nikolai Iosifovich Vilâtzak. Their partnership lasted until 1936. Stanievsky died in Poland in 1927. When Radunsky and Vilâtzak toured Siberia in 1928, they visited newspaper editors’ offices to familiarize themselves with local news and keep their finger on the pulse of the people. They knew that today’s concerns would immediately impact their audience.

Art & Control in the Soviet Union

Political jokes made people laugh at serious situations. Humor became a way to take a public jab at new social issues that replaced the old ones. Comedy also helped people survive or resist difficult circumstances.

Socialist idealism evolved into Socialist Realism as the wild days of the October Revolution shifted to tighter control. Artists who failed to toe the party line risked suppression and arrest. With the death of Vladimir Lenin, the struggle for succession, and Joseph Stalin’s rise to power, the focus shifted from spreading world communism to establishing communist domination at home. From film and theater to the circus, art aimed to promote the virtues of Soviet life (Miller, 1999, p. 194-195).

Designed by Joseph Stalin to consolidate control over the Communist Party, eliminate rivals, and suppress dissent, the Great Purge and the waves of political terror that preceded it had an impact on what people said—or didn’t say. People who spoke out against the government risked a severe sentence under the infamous Article 58 of the Soviet penal code.

Bim-Bom’s subtle criticisms and ambiguous anti-humor walked the line between subversion and therapeutic relief. They remained popular with the people because they targeted the Bolsheviks with their wit and kept the anger of the day always present in their repertoire (Von Geldern, 1993, p. 114).

Art Belongs to the People

Lenin declared that “Art belongs to the people.” Bim-Bom brought it to them.

Over the years, Bim-Bom performed their cutting political satire. They dodged being used as propaganda machines and put their spin on current topics that mattered to their audiences in a clever and public form of artistic resistance.

The crowd roared with approval whenever the orchestra started playing to announce Bim-Bom’s appearance. It was hard to gain status as a public favorite, but once Bim-Bom won the public’s love, they remained eternal favorites, giving them a semi-protected status during uncertain times. One winter, they gave a charity benefit performance with inflated prices, but the circus sold out, and bouquets and expensive gifts covered the stage.

Surviving Stalin

Under Stalin, restrictions on artists tightened. In the 1930s, at the height of the Great Purge, Bim-Bom erased political satire from their act. Instead, they stuck to musical routines.

During World War II, circus performers toured the Eastern Front to boost Soviet soldiers’ morale. In 1939, on the eve of Adolf Hitler’s invasion of Poland, Radunsky received the title “Honored Artist of the RSFSR.” In the postwar years, from 1946 to 1948, Radunsky performed alone.

In 1953, Stalin died. The following year, Radunsky published his circus memoirs, Notes of an Old Clown. Radunsky, the original half of the Bim-Bom duo, lived several years into the Khrushchev era. For almost 60 years and several regime changes, Radunsky outwitted and entertained a Soviet generation with public truths that others only dared whisper.

References

Evdokimova, Irina, Slav N. Gratchev, and Margarita Marinova, eds. (2021). Russian Modernism

in the Memories of the Survivors: The Duvakin Interviews, 1967-1974. University of Toronto Press.

Figes, Orlando. (1997). A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891-1924. Penguin

Books.

Geldern, James von. (1993). Bolshevik Festivals, 1917-1920. University of California Press.

Jahn, Hubertus. (1998). Patriotic Culture in Russia During World War I. Cornell University

Press.

Kotin, Stephen. (2015). Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928. Penguin Books. Vol. I.

Leach, Robert. (1994). Revolutionary Theater. Routledge.

Leach, Robert, Victor Borovsky, eds. (1999). A History of Russian Theater. Cambridge

University Press.

Miller, Tyrus (1999). Late Modernism: Politics, Fiction, and the Arts Between the World Wars.

University of California Press.

Neirick, Miriam (2012). When Pigs Could Fly and Bears Could Dance: A History of the Soviet

Circus. University of Wisconsin Press.

Seldes, George. (1995). Witness to a Century. Ballantine Books.

Stites, Richard (1992). Russian Popular Culture: Entertainment and Society since 1900.

Cambridge University Press.

Terbish, Baasanjav. (2022). State Ideology, Science, and Pseudoscience in Russia: Between

the Cosmos and the Earth. Lexington Books.

Ulam, Adam B. (1998). The Bolsheviks: The Intellectual and Political History of the Triumph of

Communism in Russia. Harvard University Press.