The Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939) was one of the most brutal and bloody conflicts of all time. Spain may have been the battleground, but the scope was far larger, as people from all over the world joined or were forced to join in a war of ideologies.

Fascism and communism (and anarchism and a host of other ideologies that opposed fascism) went head to head, represented by the Nationalists and the Republicans, respectively. Countries aligned with either of those philosophies used Spain as a testbed for their military equipment.

The war wasn’t just fought in geographical locations. It was fought by appealing to people’s political conscience. Recruitment and support were critical, and ideology was promoted through propaganda. While the cinema was a new and powerful weapon in this arsenal, it was the reams of posters that captured the hearts and minds of the target audience.

The Roots of Visual Propaganda in the Spanish Civil War

The position of the Republican side of the conflict relied heavily on influence from the Soviet Union, which invested heavily in providing visual propaganda to what it saw as a region ripe for communist revolution. This proved immensely effective as the Soviet government had made, by that time, massive strides in the effective use of propaganda through film and posters in the Soviet Union. Furthermore, it should be noted that the Republicans gained no help from democratic powers in Europe, which had declared neutrality in the conflict.

Through propaganda, the Republicans generated the desire to fight for a just cause that was liberal and focused on equality. The Nationalists, however, used unity as their overarching theme, rejecting the chaos and disorder that the Republicans represented. By doing this, they promoted allegiance to a single, powerful leader that could guide them through troubles – Francisco Franco.

Both sides, however, appealed to a plethora of human emotions to guide their propaganda messages. Along with visually striking imagery, posters and the symbolism employed conveyed messages to a population with varying levels of literacy, from the well-educated urbanites to the illiterate rural population.

Dehumanization

Representing the enemy as semi-human or non-human made it easier to distinguish the enemy as the “other.” This standard idea saw massive popularity in the 1930s, not just in the Spanish Civil War propaganda but in propaganda from other countries as well, and from both sides of the political spectrum. Of note were the German posters depicting Jews and communists and animalistic and evil sub-humans.

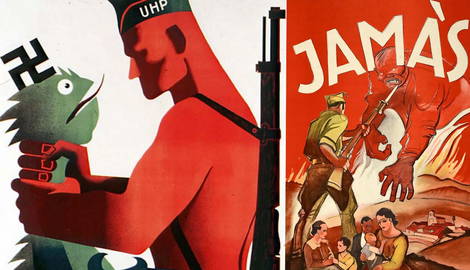

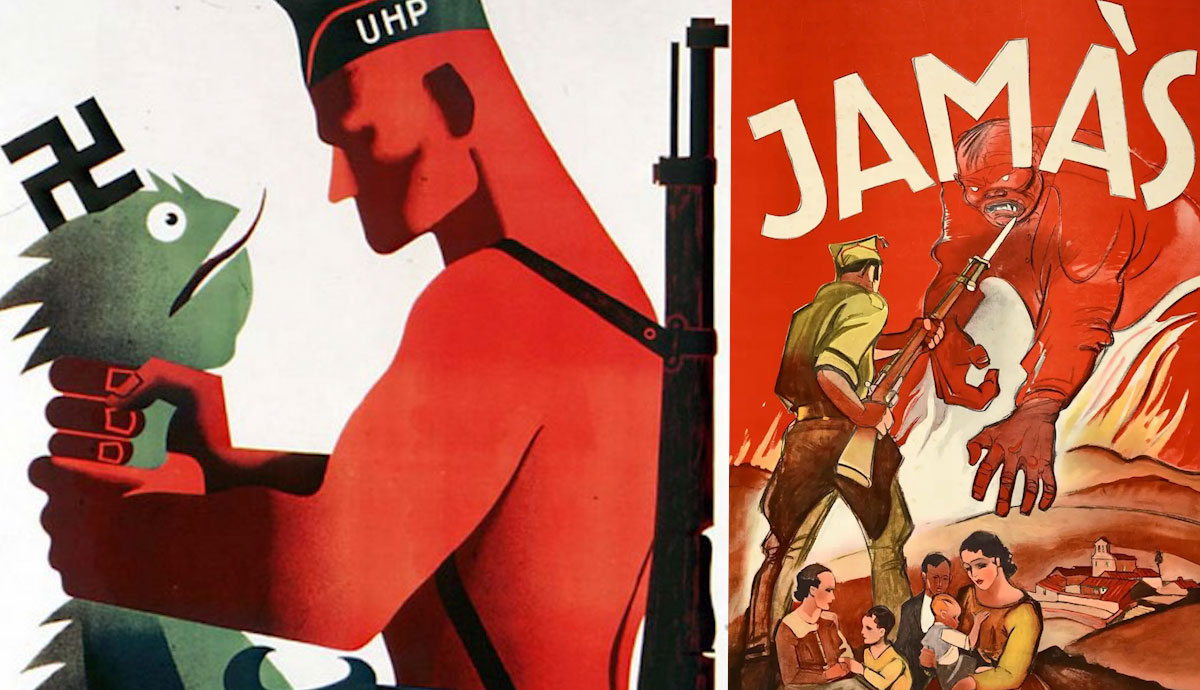

In the same vein, Republicans and Nationalists did so as well, depicting each other as snakes, reptiles, ogres, gorillas, and a plethora of other creatures lacking the qualities of humanity that were desirable.

Protecting the Family

In defending traditional norms, such as religion and social mores, the Nationalists put a strong emphasis on protecting the family. By using imagery of mothers and children under threat from communism, they could appeal to the emotions created by familial links. Just as the poster above suggests communism will destroy the family, so does the one below, with a more direct message.

Religion as a Propaganda Tool

The use of religious themes played an important part in the propaganda campaign of the Nationalists. By doing so, they managed to sway the support of much of the conservative demographic. The poster above declares Cruzada – España espiritual del mundo (“Crusade – Spain is the Spiritual Leader of the World”). Through this caption, the poster likens the Nationalist cause to that of a crusade, and in so doing, reduces their enemies to infidels. Given Spain’s history with Muslim conquest and Spanish reconquest, this message strikes a particularly powerful chord.

Appeals to Power

Propaganda is not simply powerful imagery, but it is also imagery of power. It taps into the deep need for many human beings to feel powerful. This dynamic was certainly not lost on the creators of Spanish Civil War propaganda and was found in visuals from both sides of the political spectrum.

The clenched fist is one of the most common symbols of power, and it is found here in Rafel Tona’s (1903–1987) poster above, which encourages the Catalunians to crush fascism by joining the air force.

The above image also promoted a sense of power – a fist tightened around a rifle – signifying the necessity to fight in order to secure the fatherland, food, and justice. Behind the image is the Falangist symbol of arrows and a yoke, signifying the importance of fighting for rural traditions. This was particularly useful in appealing to the conservative, rural demographic, which formed the basis of the Falangist Movement’s support.

Derision

Populists with cults of personality are enticing targets for political cartoonists who paint these characters in satire, thus diminishing their target’s attempts to create an image of all-powerfulness. In other words, no amount of power and character presentation can save you from satire.

The above poster by Juan Antonio Morales (1936) is a perfect example of derision as a propaganda device, belittling the allies of the Nationalists. Represented are the church, the Moors, Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Italy on the left, and Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany on the right. The mast is a gallows, and from it hangs the nation of Spain with the Nationalist motto of Arriba España (“Up with Spain”). The juxtaposition here shows the hollow words leading to the death of Spain. Although it is unclear what type of bird is depicted, it is possibly a vulture waiting to scavenge the remains of a dead Spain.

In a slightly Cubist, cartoonish style, the above image conveys a frightening image of General Francisco Franco in opposition to the Nationalist idea of him as a heroic savior. Behind him are the servile sycophants holding his cape. They represent the military, the capitalists, and the church.

The swastika on Franco’s jacket indicates that he is a puppet of the Nazi regime.

Camaraderie

Perhaps one of the most popular themes in Spanish Civil War propaganda is that of camaraderie and fighting for a just cause that is far bigger than the concerns of the individual. Posters appealed not just to Spanish people but to people worldwide who shared the ideals of the Republicans or the Nationalists.

The Republicans drew much international support from individuals by the tens of thousands. The Nationalists, although receiving a few thousand recruits from Ireland, England, the Philippines, Belarus, Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Belgium, relied more on support in the form of divisions already formed and under the control of the governments of Franco’s international allies. Italy, Germany, and Portugal supported the Nationalist cause. Of particular note was Germany’s Condor Legion, which had a significant hand in helping the Nationalists win the war.

Evocations of Disgust and Guilt in the Propaganda Posters of the Spanish Civil War:

One of the most potent emotions able to influence human beings to take action is the feeling of disgust. A powerful example of this is a poster from the Republican Ministerio de Propaganda which shows an actual photograph of a dead child. The assumption is made clear that the child was murdered by Nationalist forces. Images like these are extremely powerful and generate widespread feelings of anger and guilt over not having done something to prevent it. A modern example is the photograph of two-year-old Alan Kurdi, who died with his family in the Mediterranean after fleeing the Syrian Civil War.

The notion of guilt is commonly combined with disgust to shame the viewer into action, as seen by the above poster designed by Augusto (Augusto Fernández Sastre) in 1937, and refers to the brutal bombardment of Madrid by the Nationalists.

Propaganda posters during the Spanish Civil War reflected the ideology of the proponents as well as the social and cultural mores of the people whose minds they intended to sway. Reaching through a vast spectrum of themes, the Spanish Civil War gives us an in-depth look at the visual psychological devices used to elicit the emotions the creators and distributors needed to wage an effective war against their mortal enemies.

Further Reading & Sources:

- Hardin, Jennifer Roe. Fighting for Spain through the Media: Visual Propaganda as a Political Tool in the Spanish Civil War. 2013. Boston College University Libraries. (Download PDF)

- Garganese, Robin. Propaganda posters in the Spanish Civil War: Exploring visual and political narratives. October 2022. Europeana.

- Vergara, Alexander. Images of Revolution and War. University of California, San Diego.