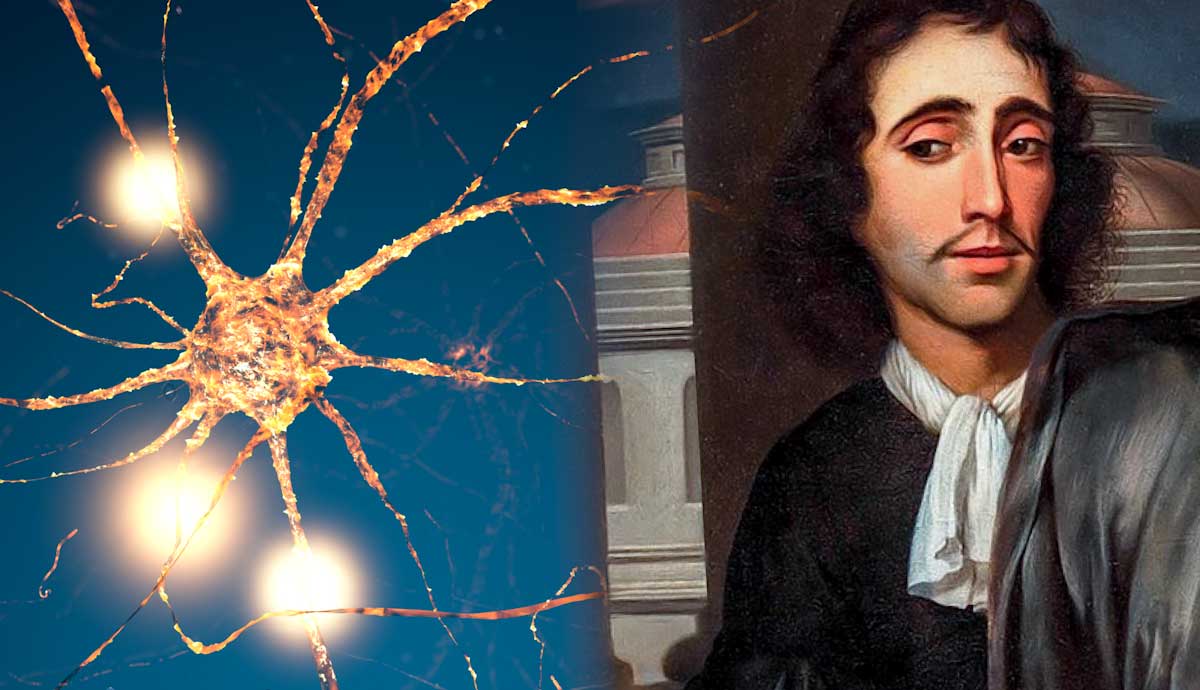

The mind-body problem is a philosophical debate that’s been around for centuries. It’s an ongoing discussion about the relationship between thought and consciousness in the human mind, and the brain as part of the physical body. Philosophers constantly argue about whether the mind and the body exist as two separate and distinct substances, or whether they are one and the same thing. Are there differences in the nature of these two substances, or are they the same? If there are, how do we get to know these differences, and how do we differentiate them? There are many approaches to this problem, but in this article, we’ll take a closer look at the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza and examine what he has to say about the mind-body problem.

1. The Philosophy of Baruch Spinoza

It’s necessary to take a look at the wider philosophy of Baruch Spinoza in order to understand his approach to the mind-body problem. His central metaphysical idea is that there exists only one substance, and we can think of this substance in two crucial ways. It is consciousness, and it has an extension (i.e., it is located in space), says Spinoza.

Rene Descartes recognized the existence of these two ways of existing and thought of them as two separate substances: one that thinks (res cogitans) and one that has extensibility (res extensa). Baruch Spinoza, on the other hand, although perhaps inspired by Descartes, does not presuppose the existence of these two types of substances as separate entities. Instead, he unites them into one substance that has these two properties, or attributes, as he calls them – thinking and extension.

Furthermore, following the continuum of this first principle and its properties, Spinoza says that reality, the world, and the universe as a whole, also have these two fundamental properties: thinking and extension. Everything that exists has these two attributes, and we can refer to reality in two different ways according to how we think of reality. If we think of the universe as extensibility, then we would have to name it “Nature.” If we think of it as consciousness, then we would have to name it “God.” “God” and “Nature” are two names that refer to one and the same substance that possesses the properties of thinking and extension, the mental and the physical.

To accept this metaphysical theory proposed by Spinoza, we have to better understand some of the words that he often uses. The term “substance” that he uses is similar to the term that Descartes uses, and it is inherited from Aristotle and medieval scholasticism:

“By substance, I understand that which is in itself and that which is understandable by itself only; i.e. that which does not need another term for another thing, from which it has to be formed.”

(Spinoza, Ethics)

Defining the term “substance” like that, Spinoza says that the only candidate for such a substance is reality as a whole. That is because of two reasons. First, that which exists, which is, is. Secondly, that which is, is everything that is; therefore, nothing can exist from which the totality of existence can depend for its existence. If there existed a cause, the one substance is the cause for itself, says Spinoza.

2. Spinoza’s Concept of God

Spinoza’s concept of God is crucial to understanding his answer to the mind-body problem. It is important to recognize the differences between his view of God and the religious view. According to Spinoza, God possesses all the traditional attributes that religion presupposes upon His nature as well: he is eternal, infinite, almighty, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent.

However, he parts ways with the Judeo-Christian concept of God when he characterizes God as the only substance. Everything is God, and there is nothing that exists outside of God, or that isn’t God. God equals the totality of everything that exists. God is not the transcendent cause for everything that exists, but rather He is, in fact, everything that exists, says Spinoza.

This means that Spinoza is a theist of a different kind: he’s a pantheist. Pantheism includes the belief and faith in God but furthermore says that there is nothing else that isn’t God, or a part of God. God equals reality.

The reason why Spinoza thinks of pantheism as the true belief in God is that he believes the attributes “infinite” and “omnipotent” only make sense if they are attributed to the totality of existence. For example, if God is not everything, then there would be something that isn’t God, and Spinoza sees this as limiting His infinity. God would not be infinite because He would be bound by something that exists outside of Him, or rather, something that isn’t Him. Similarly, if God is everything He creates, or can create everything, then God must be everything that exists or a system of existence as a whole. It cannot be that something smaller than the whole can create everything that exists, and cause everything that’s happening.

3. Human Nature

Because everything that is happening is a result of God’s nature, Spinoza thinks that human nature is a result of the essence of God as well. He says: “the essence of the human being consists of certain modes of God’s attributes.” (Spinoza, Ethics) To break this point down a bit, one needs to show the difference between attributes and modes.

Attributes are properties or characteristics that essentially belong to something. Attributes are immutable, and the things that have attributes are what they are because of them.

On the other hand, modes are also properties or characteristics, but they are not essential to the thing and do not make the thing that which it is. They are also mutable. We can even say that the mutable qualities of a certain thing are its modes. For example, if thinking is an attribute, then to have a certain idea is a mode. If extensibility is an attribute, then to have a certain form or size is a mode.

This analogy allows a better understanding of the relationship between the physical and the mental aspect in Spinoza’s philosophy. Extensibility is an attribute of God, and every given body is a separate mode of this attribute. And although there can exist a certain uniqueness and individuality in certain bodies, it’s all seen as a part of nature – as a component of the whole system of existent things known as “God”. A certain body is determined in such as way because its existence and being is a necessary consequence of what God is.

On the other hand, the human mind is a part of the infinite intellect of God. The mental life and the mental aspect of existence is a mode of one of the two attributes of God: thinking. And although there can exist a certain uniqueness and individuality in certain minds, just like in the bodies, they are all seen as a part of the divine’s mind, known as “God” – as a component of the whole system of existent things, also known as “Nature”. Hence, human beings are not substances, and their bodies and minds are not substances. They are modes of the two attributes of God, and He is the only substance. That’s why, when Spinoza says that a substance that thinks and a substance that extends are one and the same thing, he’s talking about God or Nature.

4. The Union of the Mind and the Body

Now we can finally move on to what Baruch Spinoza has to say about the mind-body problem, and why what we mentioned above is important. His approach and solution to the mind-body problem are in the accommodation of human beings within the metaphysical image of God or Nature. We are parts or aspects of one substance, he states. Just like we can understand the substance by the attribute of thinking and call it “God,” and just like we are able to understand the substance by the attribute of extension and call it “Nature,” the individual human being can be seen as a physical or a mental being in the same way. We can think of the human being as a mind or as a body. When Spinoza says that humans have a mind and a body, what he’s saying is that we all have the attributes of thinking and extensibility. On the other hand, when he says that the human mind and body are united, he’s saying that these are the two aspects or attributes of the human being.

This view of Spinoza completely rejects dualism, which presupposes two separate and distinct substances that are not united at all, as Spinoza said. Spinoza himself thought that the greatest achievement of this monist way of seeing the world is that we are totally bridging over the problem of the causal relationship of these two substances – the mental and the physical. Dualism has to face the problem of how these two substances that differ by nature are able to interact, correlate, and cooperate with each other. However, a monism such as the one defended by Spinoza completely bridges over this problem, stating that if there are no separate substances, then there is no problem with how they are united or how they causally interact with each other.

The discussion on the mind-body problem is something that has been around ever since ancient philosophy, and it’s one of those questions that only philosophers can address. Scientists are much more powerful when it comes to addressing questions about the physical world. However, science cannot contribute to the discussion at all, as it doesn’t concern itself with the meta-physical world; that task is left to philosophy. The mind-body problem shows the complexity of the philosophical way of thinking, and that’s why, to this day, there has still not been reached an agreement in regard to this problem. What Spinoza did is contribute to the discussion, but it still remains one of the most persistent questions in the history of thought.