The United States and Canadian governments have become notorious in recent years as the true breadth of their assimilation policies against Indigenous people has come to light. One of the most horrific aspects of these plans was the forced removal of children into schools that would “kill the Indian.” Often overshadowed on the global stage is the extent to which this type of assimilation programming occurred in Australia toward Aboriginal and Torres Island people. The damage left by these policies was so severe that these children went down in history as The Stolen Generations.

Note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this story may contain and provide links to images and names of deceased persons.

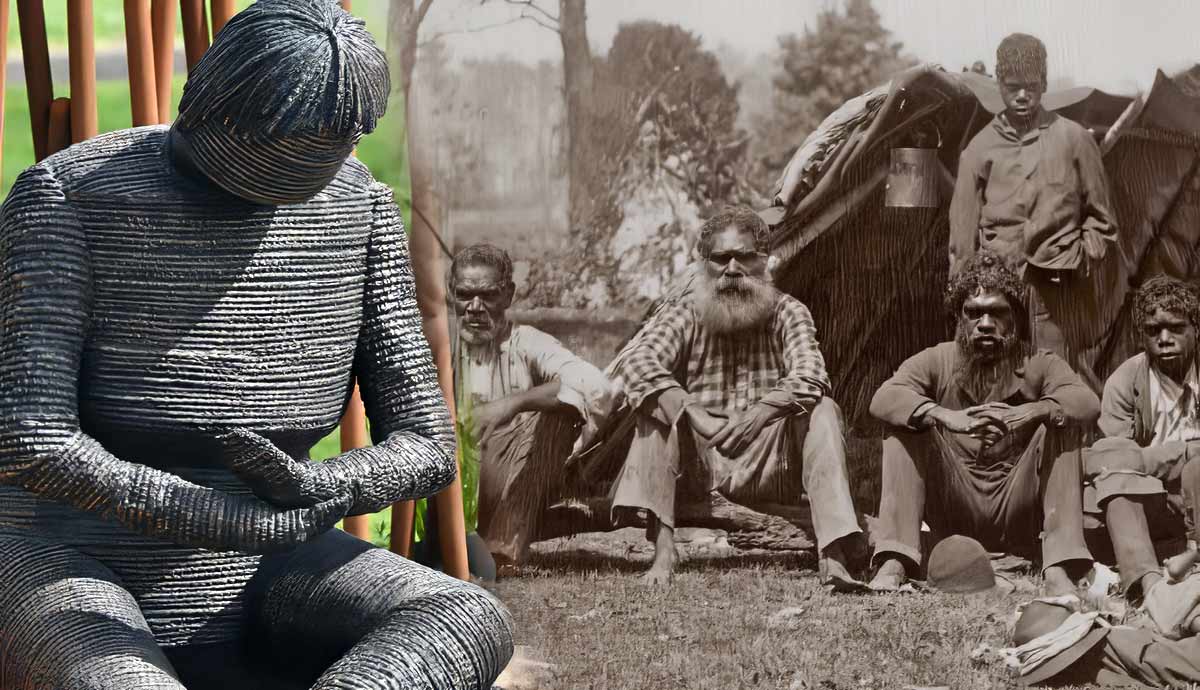

A Deep History of Inhabitancy

The presence of Aboriginal people in Australia dates back more than 45,000 years. Some historians maintain that this is the oldest population of humans to exist outside of the African continent. Generally, Aboriginal people are split into two groups: those who lived on the mainland and those who inhabited the Torres Strait Islands, which Australia annexed in the nineteenth century. However, within these designations, there are about 500 different tribal groups speaking hundreds of Indigenous languages. Today, Indigenous people make up almost 4% of Australia’s population, with just under one million individuals counted on census estimates in 2021.

At one time, it was estimated that well over one million Aboriginal people occupied the Australian continent, but that population was immediately compromised with the arrival of British settlers in 1788. In 1770, Captain James Cook had claimed the continent for the British Empire, but it would be almost twenty years before permanent settlers arrived.

The first settlement established Australia as a penal colony, as 850 convicts and a group of soldiers to oversee them arrived to create a new society. Botany Bay in Sydney, New South Wales was the location of this first encampment and became the English government center in Australia. In 1793, the first free settlers arrived from England, and the white immigrant population grew steadily.

Colonization & Genocide

Early interactions between the British and the Aboriginal peoples are widely characterized as friendly. However, as time progressed, the English population grew. It began moving further inland, seizing resources and land from Indigenous people, throwing considerations of the Aboriginal people to the wayside.

As European settlers moved inland and further away from the center of government in New South Wales, random killings of Aboriginal people were not uncommon. It wasn’t long before disease epidemics began to rage among the Aboriginal people of Australia, their immune systems facing unfamiliar bacteria and viruses shed by the encroaching colonists.

At least 270 massacres have been documented in the first 140 years of British settlement in Australia. There was resistance by the Aboriginal tribes, mostly in the form of small-scale guerilla warfare, and around 20,000 were killed in violent confrontations.

British seizure of land and supplies subjugated the Aboriginal people and resulted in impoverished communities that lacked access to their traditional methods of gathering resources. The resettlement of some tribes was instigated by the government, and in 1837, official policies toward Australia’s Indigenous people were established.

A Guise of Protection

In 1837, the British Select Committee, a division of Parliament, examined the treatment of and relationships with Indigenous people in all of the existing British colonies and outposts, including Australia. As a result, it was determined that a “Protector of Aborigines” role be established.

The Protector was charged with the welfare of the Aboriginal people; however, the definition of “protection,” as defined by this role, varies quite significantly from what a modern sensibility might assume. The Protector could essentially manage Australia’s Indigenous people under the guise of watching over their rights and saving them from oppression.

In an example of how the role of Protector was often paradoxical, the first Protector of South Australia, Matthew Moorhouse, was the leader of a party that perpetrated the Rufus River Massacre in 1841, where 30-40 Aboriginal people were killed. At the same time, Moorhouse often infuriated locals with his efforts to guard Aboriginal interests during his tenure. The inconsistencies were not unique to Moorhouse, and many “well meaning” Brits played a role in the maltreatment that was to come.

The oversight of Australia’s Indigenous people was broadened in 1863 when the Board for the Protection of Aborigines was established and in 1869 with the passing of the Aborigines Protection Act in Victoria. The control that this act offered had been sought for years, and analogous laws began spreading through other provinces, such as Queensland.

The Protection Act was the first law of its kind that granted the governor the legal ability to remove Aboriginal children from their homes. Government officials and many members of society at large believed that assimilating Aboriginal people into white culture would improve the lives of Indigenous peoples. It also had the potential to improve land access and reduce confrontations: If Aboriginal people were assimilated, they would no longer be an obstacle to English growth and expansion.

Since children were seen as more adaptable, most of these laws and efforts focused on youth. In addition, children were viewed as “useful” by many colonists as household servants or farm hands.

Legislation enveloped Australia and widened in breadth and scope. An 1886 revision extended the removal laws to include children who were mixed race, the offspring of one aboriginal parent and one white. By targeting young people, the government was not only controlling Aboriginal youth but exalting control over Aboriginal families and tribes while exterminating future generations and their relationship with Indigenous culture. By 1915, the New South Wales government could remove any Indigenous or mixed-race child for any reason. As a result, thousands of children were removed from their homes and sent to institutions.

Limited Aboriginal Rights

Children and their families weren’t the only ones affected by this subjugation. When Australia became a Federation in 1901, it was determined in the new Constitution that Aboriginal people would not be counted in the census and that the states retained complete power over Aboriginal affairs. Indigenous people were not able to vote or have Australian citizenship. Aboriginal parents were defenseless against the government’s attempts to conquer their culture via their children.

Stolen

Between 1910 and 1970, the Australian government ramped up its attempts to eliminate Aboriginal culture. Assimilation policies often targeted children, such as the expanded 1886 law that brought children with one white parent, referred to as “half caste,” into the fold. Between 10 and 33% of Aboriginal children were removed from their homes during these years.

The children were placed with adoptive (white) families to serve as servants or farm workers or institutionalized, given anglicized names, and forced to attend schools where they learned English and other aspects of white culture. They were forbidden from speaking their native tongues. These assimilation measures all traced to the idea that Aboriginal people as a race were inferior to Caucasians.

Eugenics, the idea of genetic purity and ideal human “breeding,” was a popular idea worldwide in the early 20th century, resulting in the ongoing removal of children into the next decades. Starting in the 1930s, which institution children were removed to was often based on their assessed degree of skin color.

In 1937, a conference on Aboriginal Health and Welfare was held in Canberra. This was the first time that Aboriginal “protection” and management had been discussed on a national level. At this gathering, officials agreed that assimilation, or the “ultimate absorption” of Aborigines into the Commonwealth, was the best policy.

After the conclusion of World War II, the world was left with a sour taste in its mouth in regard to eugenics after the horrors inflicted by the Nazis in Europe. However, this didn’t cause the removal of Aboriginal children to wane. Assimilation focuses shifted to social and economic concerns but persisted. Removal was said to be based on children’s welfare instead and would continue well past the midcentury mark.

Many children were told that their parents had abandoned them or had died in an effort to reduce their attachment to their old life. In addition to being forced to abandon their native language, children could not participate in any cultural or religious ceremonies, resulting in shame associated with their native heritage and even themselves. Contact with families or any aspect of Indigenous culture was not permitted. Eventually, many children came to hate Aboriginal culture, as this is the message that was repeatedly forced on them during assimilation measures.

The institutions that rose up to take possession of these children can be viewed in parallel to the residential schools in the Western Hemisphere. The schools provided some education but also instructed students in work such as housekeeping and farm trades, which would allow them to be placed with a white family in a position of servitude. This pushed the idea that Aboriginal people were not qualified to hold places in white society other than as laborers and in servitude.

The longest-running of these institutions was United Aborigines Mission Home in Bomaderry, New South Wales, which held children under 10, many of them infants. When children aged out of the home, they were turned over to the care of the Protection Board and often sent into domestic service. It wouldn’t close until 1988.

Quarter Caste Children’s Home in Western Australia is an example of how race impacted the portrayal of youth with Aboriginal ancestry, no matter how dilute. At the Quarter Caste Home and others, children were allowed limited contact with the outside world until they were determined to be assimilated. Physical and sexual abuse were not uncommon at these training facilities, of which 480 existed across the continent.

Aftermath of Assimilation

It wasn’t until 1969 that the Protection Board overseeing the removal of Aboriginal children was abolished as a result of new legislation that repealed the right of the government to remove native children with ease. Still, the children who survived this trauma, of which an estimated 17,000 survive today in Australia, known as the Stolen Generations, were left adrift.

Many felt disconnected from their heritage and were subject to intergenerational trauma, a situation in which a survivor, unable to cope with their experiences, passes residual trauma to their descendants. According to a 1997 study, children of the Stolen Generations became more likely to be involved with crime as they aged. In addition, depression was common among survivors, and they were often unable to establish their right to native title or tribal affiliation. The report also suggested that no Indigenous families were left untouched in some way by forced separation.

A Path To Healing?

The report, titled Bringing Them Home, suggested that the government should make a national apology in response to its past actions as a first step toward healing for all. In February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd issued this apology, addressed to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, but particularly those of the Stolen Generation. Though this apology could not repair all the damage that had been done, it was the first step on a path of healing for many.

Despite the recognition of the wrongs committed against the Stolen Generation and Australia’s Indigenous people as a whole, the removal of Aboriginal children nevertheless persists. In 1983, a policy, the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle, was adopted into welfare legislation in the Northern Territory, working to ensure that removed Indigenous children were placed with Indigenous families whenever possible.

Australia’s other states followed suit, adopting similar policies from 1987-2006. Though the government no longer formally endorses the removal of Indigenous children from their parents, statistics demonstrate another view. From 2012 to 2017, the number of children removed from their families and placed into state care rose from 46.6 per 1,000 children to 56.6. The rate of infant removal, in particular, rose dramatically. While the intent of child removal might not be the same at face value as it was in the twentieth century, it is still very real, and many of its effects remain consistent.

Removals are usually based on child welfare in contemporary times, accelerated by economic and social challenges among Aborigines, many based on the loss of the Stolen Generations and ongoing intergenerational trauma. Corruption within the system may also be to blame, as investigations have found that children are often removed without thorough determination if they could be placed with a family member rather than being removed from their families completely.

Australia has a long road to healing and reconciliation for the Stolen Generations. The loss of culture during those years is challenging to recapture, with languages and other cultural markers dying out permanently. Intergenerational trauma poses obstacles to healing and perpetuates the cycle of damage felt by thousands. In the Bringing Them Home report, a national apology was just one of 54 recommendations made to work toward healing. More work is required to accomplish these goals and put an end to the cycle of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander oppression in Australia.