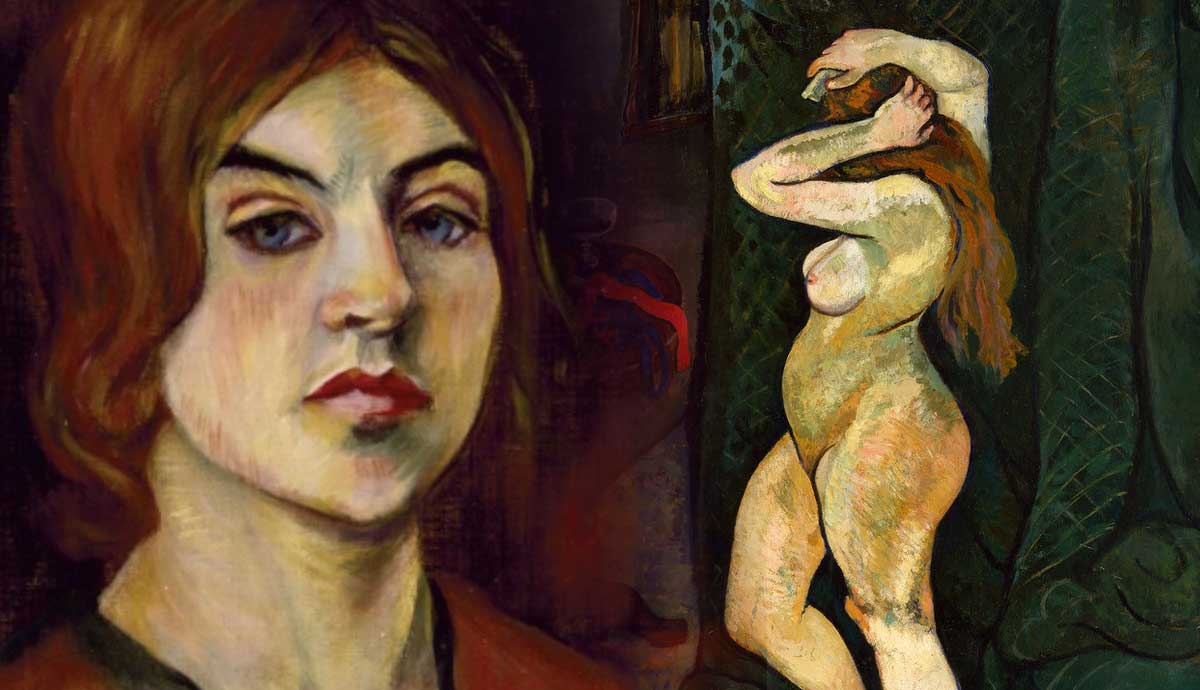

Once a model for famous artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Valadon became an artist herself. She was never formally trained to be an artist but instead started drawing as a child and learned from watching the artists that she modeled for. Her unique portrayals of the male and female nude were shockingly modern for her period. Her turbulent life as well as her art were provocative to many of her contemporaries. She got a divorce, had a young lover, and had a son who suffered from alcohol addiction since he was a teenager. Here is how Suzanne Valadon went from circus performer to artist.

Suzanne Valadon’s Time at the Circus

Suzanne Valadon was born in Bessines-sur-Gartempe near Limoges, France in 1865. Her given name was Marie-Clémentine, which she would later change to Suzanne. Her mother was an unmarried laundress. Even before Marie-Clémentine was a teenager, she did a variety of jobs to support herself. The artist attended a religious school in Paris until 1876. She then worked as an apprentice in a dressmaking shop, then as a waitress, a florist, a nanny, and as a circus performer.

When Valadon was fourteen, a new circus was built in Paris. Two painters told Valadon about it and introduced her to its owner Ernest Molier. He employed her as a trapeze artist. Valadon learned how to draw when she was nine years old and continued to draw while she worked at the circus. The bodies of the trapeze and ring performers turned out to be great subjects for her works.

Even when she got older, Valadon continued to speak fondly of her time at the circus. The fourteen-year-old Valadon fell from a trapeze during rehearsal and hurt her back. Even after several weeks of resting, she was not able to go back to work. According to her biographer June Rose, Suzanne would have probably stayed a circus artist but after experiencing a severe fall, she had to find a new career for herself.

From Model to Artist

In search of a different career, Suzanne Valadon, still in her teens, became a model for artists. She modeled for famous artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Renoir’s painting City Dance is an example of her as a model. The female dancer depicted in the image was painted after Valadon. In 1883, when Suzanne was eighteen years old, she gave birth to her son Maurice Utrillo. He would later become an artist himself. Her first signed and dated work was made the same year when she gave birth to her son.

The name Suzanne can be traced back to her time as a model. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec called her Susanna after the biblical story and popular art historical subject of Susanna and the Elders. The story is about the young and beautiful Susanna who is being watched during her bath by two elders. The nickname is a reference to Suzanne Valadon’s work as a model since she was exposed to the voyeuristic gaze of older men, just like the biblical figure Susanna.

During her time as a model, Suzanne continued drawing. She was able to watch and learn techniques from the artists surrounding her. Lautrec introduced Edgar Degas to Valadon’s drawings. She met Degas around 1890 and he became her friend, admirer of her art, and her patron. He also taught her etching and drawing techniques. Degas encouraged her to exhibit at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1894, which made her the first self-taught woman who participated in the Salon’s exhibition. The fact that Valadon was not only self-taught but also a woman from the lower class made the acceptance of her work an immense achievement.

Valadon finally became a full-time painter in 1896. She was financially supported by her husband Paul Mousis, whom she married the same year. When Valadon divorced him in 1909, her mature style started to develop. She later married a fellow painter called André Utter who was also a friend of her son Maurice Utrillo. After 1909, Suzanne Valadon’s work was regularly shown at the Salon d’Automne. In 1912, she exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants as well.

Suzanne Valadon’s Mature Period

Even though Suzanne Valadon continued to create art during her marriage with Paul Mousis, the number of works she made decreased. When their marriage ended, Valadon would begin to create works in her mature style. This included her well-known nudes. Flat, rich colors, strong, visible contours, and ornamental backgrounds are characteristic of her later work. Valadon’s painting The Blue Room is an example of her mature style. It portrays a woman with dark hair dressed in striped trousers with a cigarette in her mouth lying sideways on a bed covered with a decorative blue blanket. The image is often interpreted as defying a traditional depiction of women. Instead of being portrayed stretching out naked on the bed, available for the viewer’s gaze, the woman wears modern clothing with a cigarette in her mouth. She seems relaxed and uninterested in the viewer.

Valadon’s later work received critical acclaim. She also achieved financial success. Valadon was mentioned on the front page of Le Gaulois, a French daily newspaper where critics praised her nudes. In the 1920s, the artist was at the height of her career. In the 1930s, she exhibited in Berlin, Chicago, Prague, and New York. Therefore, she became internationally known. After a retrospective of her work at a Gallery in Paris, the artist died of a stroke.

During her life, Valadon’s art was shown in four major retrospective exhibitions. Even though Suzanne was a successful artist and critics thought of her as historically important, her work became increasingly unknown after her death. Her pieces were introduced to a larger audience during the 2021 exhibition Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel at the Barnes Foundation. This was the first major US solo exhibition dedicated to Valadon.

Suzanne Valadon’s Unique Depictions of the Male and Female Nude

Not only did Suzanne Valadon’s depiction of women differ from traditional portrayals, but she also depicted male nudes. This was quite shocking at the time. Since Valadon went from being a model who was being depicted to being the artist who depicts, she could decide and reinvent the ways in which women were portrayed in art. Her images do not show the ideal delicate female subject in a highly eroticized way, but confident women.

Even though other contemporary female artists such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt painted women as well, Suzanne Valadon’s depictions differed from theirs. In her text Returning the Gaze: Diverse Representations of the Nude in the Art of Suzanne Valadon Patricia Mathews names their class differences as one of the reasons. Valadon was an illegitimate child who grew up in precarious circumstances which allowed her to mix with male artists, learn from them, and model for them.

Modeling for artists, at the time, was similar to being a sex worker and therefore not an occupation meant for women coming from bourgeois families. For female artists with higher social standing, it was also not appropriate to freely paint many scenes of working-class women or create a nude of middle-class women. Because of her social standing, Valadon could be less inhibited in her portrayals of female subjects and their class. Valadon depicted her working-class models with diverse physical and emotional expressions, which was unusual at the time. They were commonly portrayed as objects in a highly sexualized manner.

Valadon also depicted herself and her aging body. She even painted her nude body when she was over 60 years old. The artist did not shy away from depicting the female body in a way that differed greatly from the idealized versions of her time.

What was more shocking than her depictions of women was her portrayal of the male body. Painting the male nude was virtually impossible for women from bourgeois families. Valadon often depicted the male body as an object of female desire. Since the visibility of female sexuality in art was taboo, critics ignored her male nudes. Her female nudes, on the other hand, were the topic of detailed discussions.

In her work Adam and Eve, Valadon depicts herself and her much younger partner André Utter. It is often considered the first modern work done by a female artist that shows the female nude next to a male nude. The shocking nature of the image becomes even more apparent when one considers the fact that Valadon had to add fig leaves over her partner’s genitals in order to exhibit the work at the Salon des Indépendants in 1920.