The emergence of Timur, often known as Tamerlane, represented the last major nomadic empire that stretched across much of what is today Asia and the Middle East. His empire nearly rivaled that of the Mongols nearly two centuries prior.

A Changing Empire: Tamerlane’s Time

Much of the mass of Asia, Europe, and the Middle East were united under the Mongol Empire by Genghis Khan and his successors. Genghis Khan’s ability to use nomadic cultural practices and the weakness of surrounding states created the largest contiguous empire in history.

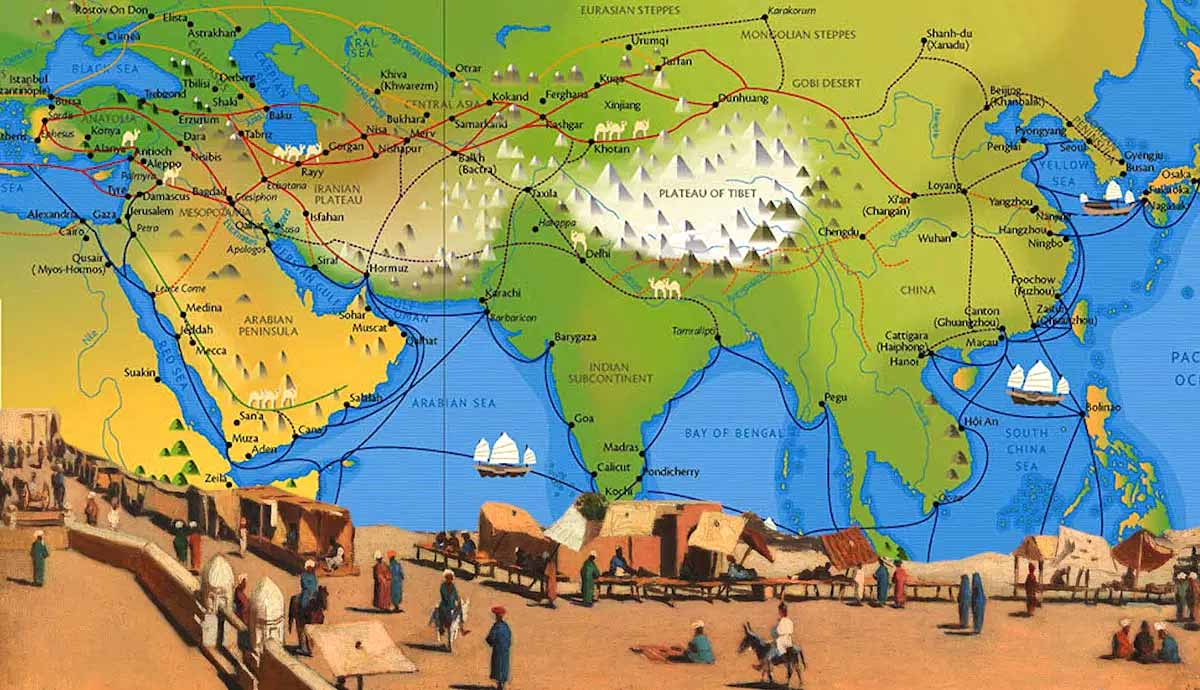

The large empire was the result of a number of factors that would be hard to replicate. Furthermore, the sheer size of the Mongol state made it difficult to administer. The Mongols were able to hold onto much of their domain for about a century through a unique and innovative system of relative autonomy and lower taxes. Trade blossomed on and around the fabled Silk Road.

However, the Mongols were not able to keep their empire together forever. Portions of the empire began to break away, as the people of China threw off the Yuan Dynasty following natural disasters and inflation. Other portions of the empire remained intact for further decades, including in parts of Central Asia and the Golden Horde across much of what is today Russia.

The Unique Opportunity

The weakness of the Mongol Empire in the 14th century allowed many of the peoples conquered by Genghis Khan and his descendants to break away after decades of foreign rule. However, the lessons learned from the Mongol conquests remained with the nomadic peoples of the Eurasian Steppe.

This included the young Timur, who was born in 1336 CE. Tamerlane believed that he was a direct descendant of Genghis Khan, although this has not been proved. However, he likely shared some distant relation with the great conqueror. Timur, later known in Europe as Tamerlane or Tamburlane, was a byproduct of the mixture of Mongol and Turkic people in Central Asia. The people of the region often sided with the Mongols during their conquests and shared a number of unique cultural characteristics from life on the Eurasian steppe.

As a young man, Timur’s heroes were the man he believed to be his direct ancestor and Alexander the Great. He sought to unite the empire that Genghis Khan had originally built. Even from birth, he shared another characteristic with the great Mongol leader. Both Timur’s name and Genghis Khan’s birth name of Temujin are based on the Mongol word for iron.

Growth Into a Leader

Timur was a bandit in his younger years, with his father likely being a minor noble among his tribe. As a young man, Timur was likely shot in the hip and hand, leaving him with a significant disability. He lost two fingers to the arrow to the hand and gained the moniker “the lame,” or “lang,” in Persian. When “Timur-i-Lang” was carried throughout his conquests, he became more popularly known in Europe as Tamerlane.

As a young adult, Tamerlane was able to build a number of important alliances in Central Asia, and became a respected military commander. In time, Tamerlane was able to consolidate control over much of Central Asia, and the remnants of the Chagatai Khanate, formed by Genghis Khan’s son Chagatai. While others ruled on the throne, he held most of the power. Tamerlane further consolidated his position by marrying Saray, a descendant of Genghis Khan himself.

Tamerlane was able to utilize his intelligence and skill to control much of Central Asia. However, he faced a significant issue due to his bloodline. While Genghis Khan emphasized merit and loyalty over every other trait, Tamerlane had to rule behind proven descendants of Genghis Khan on the throne. As the premiere Muslim military leader of the time, he also could not become the head of the religion, or the Caliph, because he could not claim descent from the Prophet Muhammad. Instead, Tamerlane was often referred to through another title, “the Sword of Islam.”

Building an Empire

Tamerlane became one of the most storied conquerors in the history of the world. He was able to defeat a number of Mongol leaders and establish himself in the mold of Genghis Khan. His career took him across much of the known world, fighting as far away as Moscow, India, and China. Tamerlane burnished his credentials through his conquest of much of the Middle East.

It is partially through this conquest that Tamerlane earned his fearful reputation, and by extension, helped shape the perception of nomadic conquerors. Upon taking the Afghan city of Herat, Tamerlane massacred much of its population. After recapturing a rebellious city in Persia, Tamerlane had its prisoners encased alive in its walls. In another case, when the Persian city of Isfahan rebelled against his heavy taxes, Tamerlane massacred up to 200,000 of its residents and created dozens of towers of human skulls. Tamerlane became the most feared of the nomadic conquerors and regularly showed a type of cruelty beyond that of a figure such as Genghis Khan.

Tamerlane proved his skill and his reputation for severity in a new campaign in India at the end of the 14th century. During the invasion, Tamerlane defeated a number of Indian armies and massacred tens of thousands of captured slaves. In capturing Delhi in 1398, Tamerlane was able to defeat an army utilizing elephants through his use of camels carrying flaming hay, causing the elephants to panic and crash into their own army. In taking Delhi, Tamerlane destroyed much of the city. He ordered the enslavement of many of its citizens, and when it attempted to rebel, he massacred much of the population and created a pyramid of human skulls.

A Terrible Reputation

Tamerlane was not quite done yet. He continued his conquests with a new campaign in the Middle East, taking on the upstart Ottoman Empire. During this fight, he captured a number of surrounding regions, including Armenia and Georgia.

His most famous siege during this time was the capture of the fabled Muslim city of Baghdad. Upon capturing the city in 1401, Tamerlane’s forces massacred much of the population, and he allegedly ordered that every soldier should return with at least two human heads. According to historians at the time, his men feared Tamerlane so much that they decapitated their own wives in order to not invite his wrath.

Tamerlane defeated the Ottoman Emperor Beyezid I after defeating him at the Battle of Ankara in 1402. This sparked a civil war that threatened to undo the immense power of the Ottoman Empire. When he attempted to follow Ottoman forces into Europe, Italian naval forces aided the retreating Ottomans out of sheer fear of Tamerlane entering Europe. The Ottoman Empire was severely weakened, but not finished. Later in the same century, the Ottomans would end the last remnant of the Roman (Byzantine) Empire with the capture of Constantinople in 1453.

Expansion and Tamerlane’s Death

Tamerlane had united much of Central Asia and the Middle East under his rule and created alliances or vassalization among the remainder of the Golden Horde and the Mongols. There would be one major piece necessary to reunite Genghis Khan’s Empire. Tamerlane bristled at a letter from the Ming Dynasty in China declaring him their subject. He planned an invasion of China during a winter campaign over the mountains. However, as an older man in difficult weather, he fell sick and died. His death would mark the beginning of the end of his empire, which was the last of the major nomadic realms.

Future empires would be marked by gunpowder and nomadic states no longer threatened their sedentary neighbors. Although it was, ironically, a former nomadic people that adapted to this new norm through technology, that lasted the longest. The Ottoman Empire would last until after the end of the First World War.

Tamerlane’s legacy was further built by the exhumation of his remains in June 1941 by Soviet social scientists, which allegedly included an inscription that disturbing his burial site would “unleash an invader more terrible than I.” Three days later, the Soviet Union was invaded by Nazi Germany in Operation Barbarossa. When reburied three years later, the Soviets won a decisive victory at Stalingrad.