John Ruskin published a newsletter in 1877 where he harshly critiqued a painting by James Whistler. Whistler responded by suing Ruskin for libel, and the resulting court case became a public spectacle, inciting broader questions about the nature and purpose of art. This case occurred, not coincidentally, towards the end of the 19th century. At this time, a shift was underway as regards the public conception and self-conception of the artists and the role of art in society. John Ruskin and James Whistler embodied the clashing views on this subject.

John Ruskin vs. James Whistler

In 1878, the artist James Abbot McNeil Whistler took the art critic John Ruskin to trial. The libel was the charge brought forward by Whistler, after taking deep offense to Ruskin’s pointed criticism of his paintings. Ruskin published the inflammatory passage in the July 1877 edition of his newsletter, Fors Clavigera, regarding an exhibition of new art at the Grosvenor Gallery in London. Here is what Ruskin wrote in disdain of James Whistler’s paintings:

“for any other pictures of the modern schools: their eccentricities are almost always in some degree forced; and their imperfections gratuitously, if not impertinently, indulged. For Mr. Whistler’s own sake, no less than for the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of wilful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

Though perhaps not quite libelous by current standards, John Ruskin’s ire is still evident in this passage. Further, it is not difficult to see why James Whistler retaliated so harshly; he had been singled out from among his contemporaries. His paintings were deemed especially lacking and presented as a new low point for the medium.

The proceedings of the court case itself were rather bleak. James Whistler, in the end, prevailed. However, his award of one single farthing amounted to quite a bit less than he had spent in court, and Whistler emerged from this debacle bankrupted. John Ruskin did not fare much better. He had fallen ill before the case, and his friend, Edward Burne-Jones, attended court on his behalf. Their involvement in the case had damaged both parties’ reputations, and this emotional toll only worsened Ruskin’s condition. The case was comprehensively ruinous for the participants. Instead, what was gained by this legal battle was insight into the nature and purpose of art as the perception of it was rapidly changing.

Embodied by John Ruskin was understanding art as a utilitarian aspect of society, reflecting and reinforcing social values. In this model, the artist has a definite responsibility to the public and must create art to the end of collective progress. James Whistler conversely represented a new articulation of artists’ role, emphasizing only their duty to create aesthetically pleasing things, to the exclusion of any other considerations.

John Ruskin’s Perspective

John Ruskin was a leading voice in British art criticism throughout the 19th century. To better contextualize his comments on James Whistler’s work and the resulting controversy, Ruskin’s established perspective on art should be considered. Ruskin spent his career as a critic asserting the virtue and value of truthfulness to nature in art. He was a famous advocate of the Romantic painter J. M. W. Turner’s work, which he felt exemplified the appropriate reverence for nature and diligence in representing it.

More broadly, John Ruskin was deeply concerned with art as a tool of societal good, believing great art had a necessary moral dimension. As a matter of fact, Ruskin’s offending comments on James Whistler were written in an issue of Fors Clavigera, a weekly socialist publication Ruskin distributed to the working people of London. For Ruskin, art was not distinct from political life but enjoyed a necessary role in it. Because of this, Ruskin was put off by Whistler’s paintings and found their deficiencies greatly concerning for more than merely aesthetic reasons.

James Whistler’s Views On Art And Nature

James Whistler, of course, felt quite differently from John Ruskin. In an 1885 lecture, Whistler proclaimed, in striking contrast to Ruskin’s stance:

“Nature contains the elements, in colour and form, of all pictures, as the keyboard contains the notes of all music. But the artist is born to pick, and choose, and group with science, these elements, that the result may be beautiful—as the musician gathers his notes, and forms his chords until he brings forth from chaos glorious harmony. To say to the painter, that Nature is to be taken as she is, is to say to the player, that he may sit on the piano. That Nature is always right, is an assertion, artistically, as untrue, as it is one whose truth is universally taken for granted. Nature is very rarely right, to such an extent even, that it might almost be said that Nature is usually wrong: that is to say, the condition of things that shall bring about the perfection of harmony worthy of a picture is rare, and not common at all.”

James Whistler found no intrinsic worth in describing nature as it is. For him, the duty of the artist was, instead, to rearrange and interpret the elements, the component pieces of nature, into something of greater aesthetic value.

Understanding The Conflict

It is essential to recognize that John Ruskin’s distaste for James Whistler was not to do with the work’s expressive or abstract style. In fact, the traces of the human in crafted objects were welcome to Ruskin, as worthy signs, he felt, of the creator’s own freedom and humanity. Moreover, these theories of Ruskin’s regarding craft and expression were foundational in establishing the Arts and Crafts movement: a group of craftspeople who fought against the callous standardization of industrial production in favor of a traditional, artisanal approach to the craft.

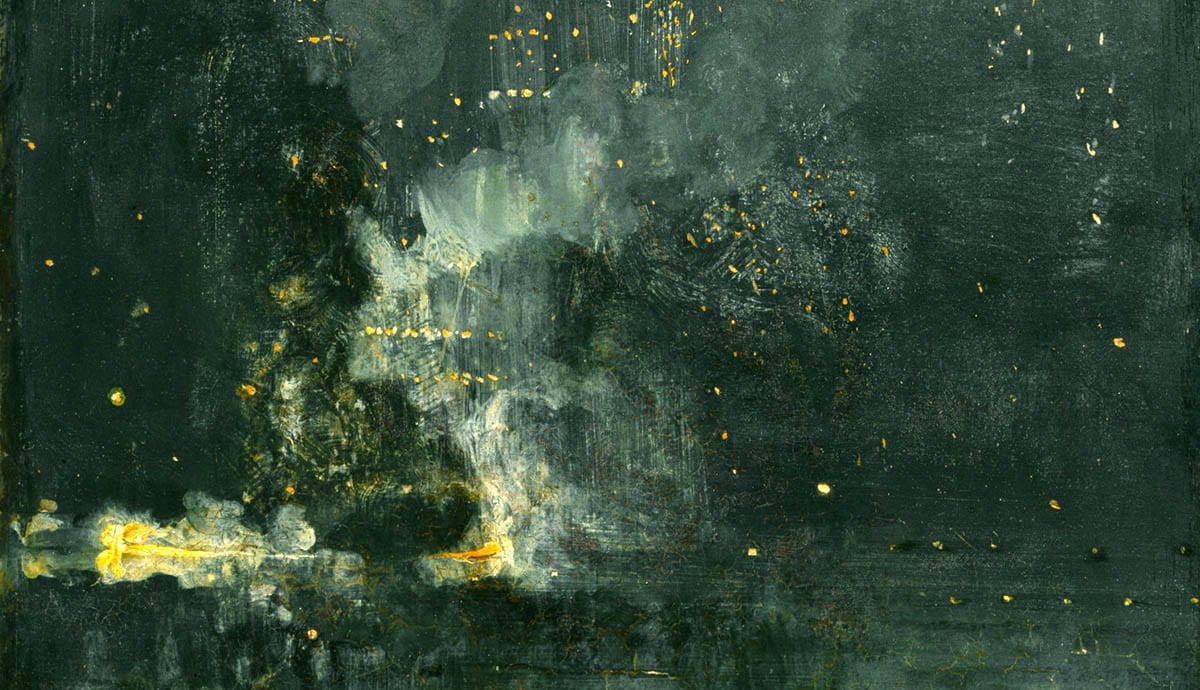

Really, the issue, as John Ruskin saw it, was with James Whistler’s failure to capture nature, to paint a reflection of its beauty and value. Though he welcomed expressive touches in all things, Ruskin could not abide carelessness. Ruskin’s ire was directed most intensely at one of Whistler’s nighttime landscapes, titled Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (now in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Art). Seeing, in this painting, Whistler’s seemingly random splatters of gold paint across a hazy backdrop, constructed with sparring and indefinite brushstrokes, Ruskin was incensed. Whistler, he felt, was painting lazily, not paying due-diligence, disrespecting his medium and subject alike.

The Implications Of John Ruskin vs. James Whistler

More than any particular stylistic quarrel, this spat between John Ruskin and James Whistler can be understood as part of a greater trend: the shifting social perception of art and artists. Ruskin’s notion was that art’s purpose was to reflect and contribute to societal good: a more traditional view, rooted in pre-modern and early modern art. This perspective was challenged by art movements in the second half of the 19th century, like Impressionism, from which attitudes like Whistler’s emerged. From Whistler and the like, the insistence was that artists had no responsibility but to make beautiful things. This stance was severe, considering that even direct predecessors to Impressionism, such as Realism, absolutely involved moral considerations of its pictures’ subjects.

In some sense, it was the old, socially concerned model of art theory which was brought to trial, in the form of John Ruskin. Though James Whistler’s victory amounted to negative personal gain, it signaled something much larger: his version of the artist as a detached and pure aesthete, involved primarily in formal innovation, was seen to triumph here. Indeed, it would be this new vision of art and artists which grew more hegemonic as modernism ran its course, resulting in a cascading series of movements involving less and less of an overtly social and moral dimension.