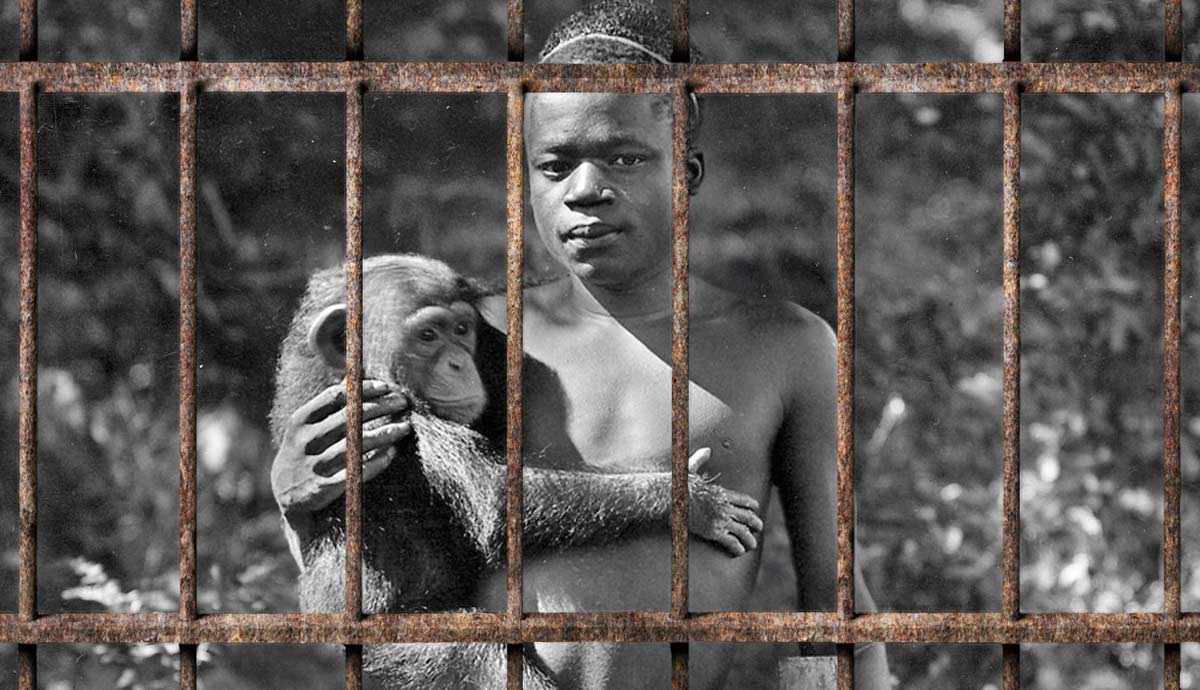

In 1904, Ota Benga, a 23-year-old man from the Belgian Congo, was kidnapped by slave traders, sold to an American, and transported to the United States. In the name of “science,” Benga endured the dehumanizing experience of being exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair and notoriously, in a monkey cage at the Bronx Zoo, New York City. The display of Ota Benga was intended as a “scientific” and “educational” experience designed to educate the public about the superiority of their race and the attendant inferiority of black people.

The disturbing and ultimately tragic story of Ota Benga highlights the precarious status of black life and its value in early nineteenth-century America, some four decades after the abolition of American slavery.

From Congo to St. Louis

Little is known about Ota Benga’s early life. He was born amidst the unspeakable colonial horror of King Leopold of Belgium’s Congo Free State. Benga lived in the equatorial forests around the Kasai River, in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. His life took a tragic turn after his wife and two children were murdered during a raid on his village by a neighboring tribe. He was captured by local slave traders and sold in 1904 to Samuel Phillips Verner, an American opportunist and self-described explorer, for goods worth less than $5.

Verner initially aimed to establish a Christian mission in the Congo Free State, but his plans faltered. Looking to business opportunities instead, he collaborated with the organizers of the St. Louis World’s Fair, offering to secure “pygmies” for a US-sponsored exhibit. Under the pretense of “scientific interest,” Verner brought Ota Benga and several other men from neighboring villages to America.

Ota Benga at the World’s Fair

At the St. Louis World’s Fair, Ota Benga and four other “pygmies” were displayed alongside other indigenous peoples from around the world. Forced to wear “native” attire and dwell within “villages” that had been made for them, the “exhibits” were treated with curiosity – and disdain – rather than as human beings.

The “Congo Pygmies” were subjected to public viewing, and when the public was not around, were studied and measured by scientists – racial anthropologists – who declared the “specimens” to be evidence of the supposed inferiority of non-European peoples. Benga was singled out from the others and advertised as a “cannibal” as visitors flocked to gawk at his small stature and sharpened teeth.

After the fair, Ota Benga briefly returned with Verner to Congo but soon requested to return to America, believing that there was nothing left for him in his native land. When he returned to America, Verner abandoned him and he was placed in a private room at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He was moved to the Bronx Zoo after throwing a chair at Mrs. Guggenheim, a major patron of the museum (Pittas, 2011).

Life in the Bronx Zoo

Initially, Ota Benga was brought to the Bronx Zoo as a caretaker, though there is no evidence he was ever paid. His presence soon became an attraction, as crowds mocked his appearance, heckled him, and even assaulted him. At some point, it was decided that he would be put on display in one of the monkey cages.

In 1906, under the guise of ethnographic education, Ota Benga became an exhibit. Zoo Director William Hornaday, with the enthusiastic support of the Secretary of the New York Zoological Society, Madison Grant, put Benga on display in the Monkey House with an Orangutan called “Dohong.” At the same time as Hornaday publicly condemned the “horror” of American slavery, he justified Benga’s degradation as a “scientific” endeavor.

Ota Benga’s daily routine included posturing with a bow and arrow, playing to the crowds, or sitting silently and visibly distressed, as thousands of daily visitors laughed and jeered at him. The cruelty of his captivity drew growing national and international outrage. Eventually, a group of black clergymen secured his release.

Later Life and Death

Upon his release from the Bronx Zoo, Ota Benga was sent to a children’s orphanage in Brooklyn (despite being an adult). Eventually, in 1910, he was moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, where he studied at the Virginia Theological Seminary. He was given European clothing and his teeth were capped, to “civilize” his appearance. Benga excelled academically but found little joy in his studies. Instead, he took pleasure in teaching local boys to hunt and fish.

Benga later worked in a Lynchburg tobacco factory and dreamed of returning to Congo. However, the outbreak of World War I halted transatlantic travel and his hopes faded. On 20th March 1916, in a tragic act of desperation, Ota Benga removed the caps off his teeth, built a ceremonial fire, and ended his life with a single bullet to the heart.

It is difficult to comprehend the suffering of Ota Benga in the United States. He was humiliated, degraded, and stripped of his dignity, as his captors justified their cruelty as a duty to science. His story exposes the impact of European ideologies of racism that still persist to this day.