Originating from Celtic Europe, the Galatians had a profound impact. Their abrupt arrival in the Hellenic world was as shocking to that classical culture as ‘barbarian’ migrations were to Rome’s early development. Such was their impact that they would influence the political landscape of much of the Hellenic and Roman worlds for centuries. Few peoples in history have had a developmental journey as fascinating as the Galatians.

The Galatians’ Ancestors

The Galatians’ origins can be traced back to an ancient Celtic group that centered in Europe from as early as the 2nd millennium BCE. The Greeks had known the Celts since at least the 6th century BCE, mainly via the Phoenician colony of Marseilles. Early references of these strange tribal peoples were recorded through Hecataeus of Miletus. Other writers like Plato and Aristotle mentioned the Celts often as being the wildest of peoples. From the 4th century BCE, the Celts also became known as some of ancient history’s most prolific mercenaries, employed in many parts of the Graeco-Roman Mediterranean.

In the Greek world, like the Roman, such observations reduced the Celts to a few well-worn cliches and tropes. Celts were celebrated for their size and fierceness and known for being wild, hot-headed, and ruled by animal passions. In Greek eyes, this made them less than rational:

“Hence a man is not brave if he endures formidable things through ignorance …, nor if he does so owing to passion when knowing the greatness of the danger, as the Celts ‘take arms and march against the waves’; and in general, the courage of barbarians has an element of passion.” [Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 3.1229b]

The classical civilizations of ancient history painted the Celts as savage, warrior people, uncivilized and simple in their animal passions. Greeks and Romans grouped ‘barbarian’ tribal people into clumsy stereotypes. Thus, to the Romans, Galatians would always be Gauls, no matter where in the world they hailed. The city-dwelling Greeks and Romans feared the massive migratory behavior of these volatile people. It represented an existential threat, as elemental and volatile as any force of nature, like an earthquake or tidal wave.

Strange customs were observed, exaggerated, and often misunderstood. The behavior of women, the raising of children, religious practices, and a wild attitude to drinking were all well-established classical tropes. Although their strength and prowess could be admired, it tended to be fetishized and did not invoke anything close to human empathy. The Celts were viewed with the shock-fascination, cold cruelty, and cultural disdain that ‘civilized’ people have always shown towards ‘primeval’ peoples.

The Celts did not leave any written testimony of their own history. We must therefore carefully and critically rely on the culturally prejudiced observations of the classical world.

The Celts Migrate

Over centuries, the Celts faced huge migratory pressures that would shape ancient Europe. Moving as entire peoples in a generational conveyor, tribes spread southward over the Rhine (into Gaul), the Alps (into Italy), and the Danube (into the Balkans). Various Celtic tribes sought land and resources and were also driven by other populations, forcing them from behind. At various times, this pressure cooker would explode into the Greek and Roman worlds.

History has many ironies and an anecdotal story of Alexander the Great’s Thracian campaign of 335 BCE is one such example:

“… on this expedition the Celti who lived about the Adriatic joined Alexander for the sake of establishing friendship and hospitality, and that the king received them kindly and asked them when drinking what it was that they most feared, thinking they would say himself, but that they replied they feared no one, unless it were that Heaven might fall on them, although indeed they added that they put above everything else the friendship of such a man as he.” [Strabo, Geography 7.3.8.]

It is ironic that within just two generations after his death, the ancestors of these tribesmen would threaten Alexander’s golden legacy. Massive Celtic movements would flood through the Balkans, Macedon, Greece, and Asia Minor. The Celts were coming.

Holidays in Greece: The Great Celtic Invasion

The Celtic collision with the Hellenic world came in 281 BCE when a mass invasion of tribes (reportedly more than 150,000 soldiers) descended into Greece under their chieftain Brennus:

“It was late before the name “Gauls” came into vogue; for anciently they were called Celts both amongst themselves and by others. An army of them mustered and turned towards the Ionian Sea, dispossessed the Illyrian people, all who dwelt as far as Macedonia with the Macedonians themselves, and overran Thessaly.”

[Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.4]

Brennus and the Celts sought to ravage Greece but could not force a strategic pass at Thermopylae. Although they did outmaneuver the pass, they were defeated in 279 BCE, before they could sack the sacred site of Delphi. This mass invasion caused an existential shock in the Greek world and the Celts were portrayed as the complete antithesis to ‘civilization’. Think biblical ‘end of days’ angst!

It was an arm of this fearsome Celtic invasion that would bring forth the Galatians.

Arrival in Asia Minor: Birth of the Galatians

By c. 278 BCE, a totally new people burst into Asia Minor (Anatolia). In a complete reversal of modern history, they initially numbered as few as 20,000 people, including men, women, and children. This was the true birth of the ‘Galatians’.

Under their tribal leaders Leonnorius and Lutarius, three tribes, the Trocmi, the Tolistobogii, and the Tectosages crossed the Hellespont and Bosporus from Europe onto the Anatolian mainland.

Then truly, having crossed the narrow strait of the Hellespont,The devastating host of the Gauls shall pipe; and lawlesslyThey shall ravage Asia; and much worse shall the god doTo those who dwell by the shores of the sea.”

[Pausanias, History of Greece, 10.15.3]

The tribesmen were transported into Asia by Nicomedes I of Bithynia to fight a dynastic war with his brother, Ziboetas. The Galatians would later go on to fight for Mithridates I of Pontus against Ptolemy I of Egypt.

This was a pattern that would define their relationship with the Hellenic Kingdoms. The Galatians were useful as hired muscle, though as time would show, the Hellenic states were not really in control of the wild fighters they had welcomed in.

The region the Galatians entered was one of the most complex of the ancient world, overlaid with indigenous Phrygian, Persian, and Greek cultures. The successor states to Alexander the Great’s legacy controlled this area, yet they were deeply fragmented, fighting protracted wars to consolidate their kingdoms.

Neighborhood Tensions: A Legacy of Conflict

The Galatians were anything but docile. Constituting considerable power in western Anatolia, they soon exercised dominance over local cities. Coercing tribute, it was not long until these new neighbors became quite the nightmare.

After a series of tumultuous interactions with the now destabilizing Galatians, the Seleucid King, Antiochus I defeated a major Galatian army, partly through the use of war elephants at the so-called ‘Battle of the Elephants’ in 275 BCE. The superstitious Celts and their panicking horses had never seen such animals. Antiochus I would adopt the name ‘soter’, or ‘savior’ for this victory.

This was a precursor to the Celts’ moving inland from the coastal regions to the hinterland of Anatolia. Eventually, the Galatians settled on the high Phrygian plains. This is how the region earned its name: Galatia.

In the decades following, Galatian relations with other kingdoms were complex and unstable. Relative superpowers like the Seleucids could, to some extent, contain the Galatians in the hinterlands of Anatolia—either by force or gold. However, for other regional players, the Galatians represented an existential threat.

The feisty city-state of Pergamon initially paid tribute to the Galatians who terrorized its satellites on the Ionian coast. Yet this ended with the succession of Attalus I of Pergamon (c. 241-197 BCE).

“And so great was the terror of their name [The Galatians], their numbers being also enlarged by great natural increase, that in the end even the kings of Syria did not refuse to pay them tribute. Attalus, the father of King Eumenes, was the first of the inhabitants of Asia to refuse, and his bold step, contrary to the expectation of all, was aided by fortune and he worsted the Gaul’s in pitched battle.”

[Livy, History of Rome, 38,16.13]

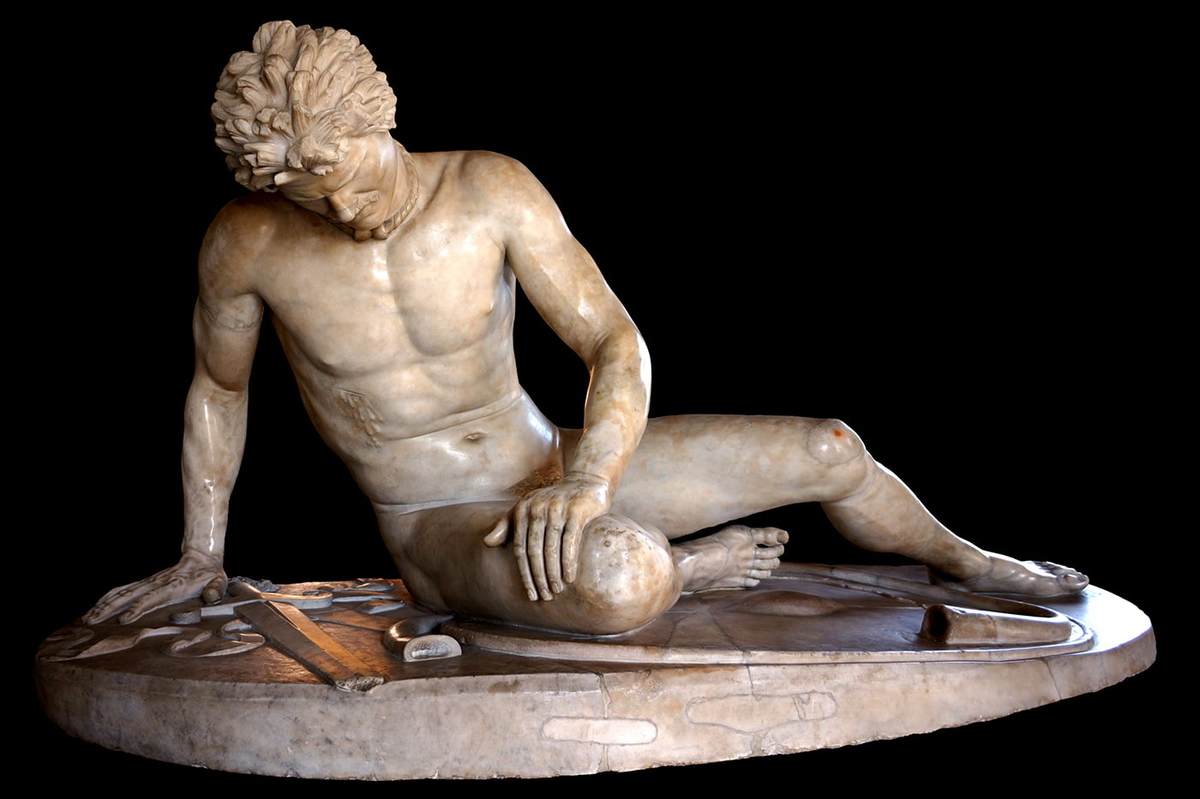

Styling himself as a protector of Greek culture, Attalus also won a great victory against the Galatians at the River Caïcus in 241 BCE. He, too, adopted the title of ‘savior’. The battle became an emblem that defined an entire chapter of Pergamon’s history. It was immortalized through famous works like the Dying Gaul, one of the most iconic statues of the Hellenistic period.

By 238 BCE, the Galatians were back. This time they were allied with the Seleucid forces under Antiochus Hierax, who sought to terrorize western Anatolia and subdue Pergamon. However, they were defeated at the Battle of Aphrodisium. Pergamon’s regional dominance was secured.

The Hellenic states of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE had many more conflicts with the Galatians. But for Pergamon, at least, they would never pose such an existential threat again.

Galatian Culture

Of the Galatian tribes, we are told that the Trocmi, the Tolistobogii, and the Tectosages shared the same language and culture.

“… each [tribe] was divided into four portions which were called tetrarchies, each tetrarchy having its own tetrarch, and also one judge and one military commander, both subject to the tetrarch, and two subordinate commanders. The Council of the twelve tetrarchs consisted of three hundred men, who assembled at Drynemetum, as it was called. Now the Council passed judgment upon murder cases, but the tetrarchs and the judges upon all others. Such, then, was the organization of Galatia long ago…”

[Strabo, Geography, 12.5.1]

In lifestyle and economy, the Anatolian uplands favored a Celtic way of life, supporting a pastoral economy of sheep, goats, and cattle. Farming, hunting, metalwork, and trade would also have been key features of Galatian society. Pliny, writing later in the 2nd century CE, noted that the Galatians were famous for the quality of their wool and sweet wine.

The Celts were not famed for their love of urbanization. The Galatians either inherited or fostered several indigenous centers, such as Ancyra, Tavium, and Gordion, as they integrated with local Phrygian Hellenic culture. Historians believe that intense cultural contact resulted in the Galatians becoming Hellenized and learning from the Greek and various indigenous peoples of the region.

Another key component of Galatian culture was war. These fierce tribal warriors cemented their reputation as paid mercenaries for many Hellenic Kingdoms, as need, expediency, or reward demanded:

“The kings of the east then carried on no wars without a mercenary army of Gauls; nor, if they were driven from their thrones, did they seek protection with any other people than the Gauls. Such indeed was the terror of the Gallic name, and the unvaried good fortune of their arms, that princes thought they could neither maintain their power in security, nor recover it if lost, without the assistance of Gallic valor”.

[Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus 25,2]

Exacting tribute from weaker neighbors, they also fought in the service of rulers as far afield as the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt.

The Roman Period

The early second century BCE saw the growing influence of Rome come into the region. After defeating the Seleucid empire in the Syrian War (192-188BCE), Rome came into contact with the Galatians.

In 189 BCE, the consul Gnaeus Manlius Vulso undertook a campaign against the Galatians of Anatolia. This was punishment for their support of the Seleucids, though some claimed the real reason was Vulso’s personal ambition and enrichment. After all, the Galatians had amassed wealth from their warlike activities and coercion of the Greek cities.

With their ally Pergamon – which eventually ceded its entire kingdom to Rome in 133 BCE – the Romans typically showed little tolerance to the ‘bad boys’ of Asian Minor. The Galatians suffered two great defeats in this brutal war, at Mount Olympus and Ancyra. Many thousands were killed or sold into slavery. The Romans would now shape the remaining history of Galatia.

When Rome later suffered setbacks in Asia during the Mithridatic Wars (88-63 BCE), the Galatians initially sided with Mithridates VI, the king of Pontus. It was a marriage of convenience, destined not to last. After a bloody falling-out between the allies in 86 BCE, Mithridates had many of the Galatian princes massacred at a banquet which made the ‘red wedding’ look like a tea party. This crime precipitated a shift in Galatian allegiance to Rome. Their prince Deiotarus emerged as a major Roman ally in the region. Ultimately, he backed the right horse. Rome was here to stay.

By 53 BCE, during a later war against Parthia, the Roman general Crassus passed through Galatia on his way to his fated defeat at Carrhae. Crassus probably drew support from Rome’s ally:

“… [Crassus] hurried on by land through Galatia. And finding that King Deiotarus, who was now a very old man, was founding a new city, he rallied him, saying: ‘O King, you are beginning to build at the twelfth hour.’ The Galatian laughed and said: ‘But you yourself, Imperator, as I see, are not marching very early in the day against the Parthians.’ Now Crassus was sixty years old and over and looked older than his years.” [Plutarch, Life of Crassus, 17]

With this Galatian sass and near laconic wit, we can discern the sharpest of minds.

Deiotarus went on to play a complex role in changing allegiances in the Roman civil wars (49-45 BCE). Despite backing Pompey, the Galatian was later pardoned by the victorious Julius Caesar. Although he was punished, Rome eventually recognized him as the King of Galatia and senior to the other Tetrarchs. He seems to have established a dynasty that lasted several generations. Galatia would be progressively assimilated into the Roman empire.

A Changing and Enigmatic People

The long history of the Galatians is so patchy that we hear only fragmentary episodes and gain fleeting glimpses of this fascinating people. Matched with enormous gaps in the archaeological record, it is often impossible not to be anecdotal about them. Yet, what we do know about them, shows a fascinating people full of character and spirit.

One example is the Galatian Princess Camma. A priestess of Artemis, Camma was coveted by the Tetrarch, Sinorix. Yet Camma was happily married and Sinorix was getting nowhere. So, he murdered her husband, Sinatus, and sought to compel the priestess to be his wife. This was a ‘rough wooing’ and the indomitable Camma had only one card to play. Acting along and mixing a libation which she shared with her vile suitor, Camma only revealed her true resolve when Sinatus had drunk from their shared cup:

“I call you to witness, goddess most revered, that for the sake of this day I have lived on after the murder of Sinatus, and during all that time I have derived no comfort from life save only the hope of justice; and now that justice is mine, I go down to my husband. But as for you, wickedest of all men, let your relatives make ready a tomb instead of a bridal chamber and a wedding.”

[Plutarch, The Bravery of Women, 20]

Camma died happily as her poison avenged her husband. Women were tough in Galatia.

Camma’s story is not dated, but it indicates that Galatians worshiped Artemis. This suggests real cultural assimilation within the region. In examples of later Galatian coins, we see Phrygian-influenced deities like Cybele, and Graeco-Roman gods, like Artemis, Hercules, Hermes, Jupiter, and Minerva. It’s not clear how such worship evolved or how it related to evidence of more primeval Celtic practices like human sacrifice. The archaeological evidence at some sites suggests these may have co-existed.

By the ’40-’50s CE, St Paul traveled in Galatia, writing his famous Epistles (Letters to The Galatians). He was addressing the very earliest churches of what was still a pagan people. The Galatians would be among the earliest people in the Roman Empire to convert to Christianity from among the non-Jews (gentiles). Yet taming such fierce people was no walk in the park:

“I am afraid I have labored over you in vain.”

[St Paul, Epistles, 4.11]

This was dangerous work and at Lystria (in central Anatolia), Paul was stoned and almost killed. Yet, just as the Galatians had been Hellenized, just as they were increasingly Romanized, so they would be Christianized.

Perhaps the last insight that we have of Galatians is fleeting. While the mid to late 4th century CE saw Rome increasingly facing threats from new barbarian tribes, we are told this story of the Achaean governor, Vettius Agorius Praetextatus:

“… his intimates tried to persuade him to attack the neighboring Goths, who were often deceitful and treacherous; but he replied that he was looking for a better enemy; that for the Goths the Galatian traders were enough, by whom they were offered for sale everywhere without distinction of rank.”

[Ammianus, Marcellinus, 22.7.8]

History has a dark sense of irony. Our view of the Galatians – a barbarian Celtic people assimilated over centuries of bloody conflict into the classical world – ends with Galatian traders as fully integrated citizens and slavers of the later Roman empire.

The Galatians: A Conclusion

So that’s the Galatians. Migrants, travelers, warriors, mercenaries, farmers, priestesses, traders, and slavers. The Galatians were all these things and more. We know so little about this amazing and enigmatic people. Yet, what we see is an incredible journey through ancient history.

Although they are often hailed as one of the most successful of the Celts, make no mistake about it; their history was bloody and traumatic. The Galatians survived and found their place, but they suffered over many generations. Fearsome, warlike, and wild, they were a people that fought hard for survival.

The Galatians clawed their way through history, though that is only half their story. Over a remarkably short period, they also successfully integrated. These Celts were Hellenized, Romanized, and, eventually, Christianized. To have the resilience of a Galatian would be a superpower indeed.