The Great Molasses Flood is one of the most interesting and least popular disasters to occur in the United States in the 20th century. The flood, a circumstance of poor engineering and greed, resulted in the death of almost two dozen people and countless animals. The mess left behind took weeks to clean up and years to overcome economically and emotionally. Buildings were destroyed, and an elevated train rail had to be rebuilt. The disaster prompted more expert witness use in court cases moving forward, a positive outcome from such a tragic, preventable disaster. Today, residents

swear you can still smell the sweet molasses scent on warm days near the Boston Harbor.

A Sticky Situation

In the early 1900s, the main commercial port in Boston, Massachusetts was located at the City’s north end, at Copp’s Hill. At the time, it was one of the busiest ports in the US since all the shipping that left this Boston harbor was headed for the East Coast or Europe. With Prohibition close to becoming law in the US and the want for alcohol high, Boston became a major player in the triangular trade and was the storage center for most of the molasses traded.

Molasses, the residue left when sugar cane is boiled to extract sugar, is used for many purposes, such as making rum, producing cattle feed, and cooking. In fact, it’s a key ingredient for ginger snaps, gingerbread, Boston brown bread, and Boston baked beans. In World War I, it had even been used used to make ammunition.

The “triangular” trade was an economic boon for multiple geographic locations. Plantation owners in Jamaica and Barbados would process their sugar cane, then transport the molasses to Boston, where the distillers would make rum. The rum was then shipped to Africa and traded for enslaved people, who were, in turn, transported back to the Caribbean Islands to work the plantations and maintain the sugar cane crops.

A Troublesome Tank

In 1915, The Purity Distilling Company had a large tank built. The 50-foot-tall tank was made from state-of-the-art steel from the period. (Albeit the same type of brittle steel used on the Titanic just seven years prior.) The thickness of the steel did not hold up to the heavy, sticky substance, and it was never structurally sound. It was put up hastily and was not inspected prior to use as it should have been. Residents living in and around the port would often comment on how the tank groaned and shuddered each time it was filled. It leaked from the beginning, and local children often brought their pails to the tank and collected the leaking molasses.

The company that owned Purity Distilling, US Industrial Alcohol, had been in a rush to build it and had employed a contractor who was not an expert in engineering but rather an expert in finance. This unequipped contractor lacked technical training and safety expertise and was said to be unable to read blueprints. This led to the poor structure of the tank and the subsequent leakage. When the company was made aware of the leaking tank, its solution was to paint it brown to disguise the leaks.

The Great Molasses Flood

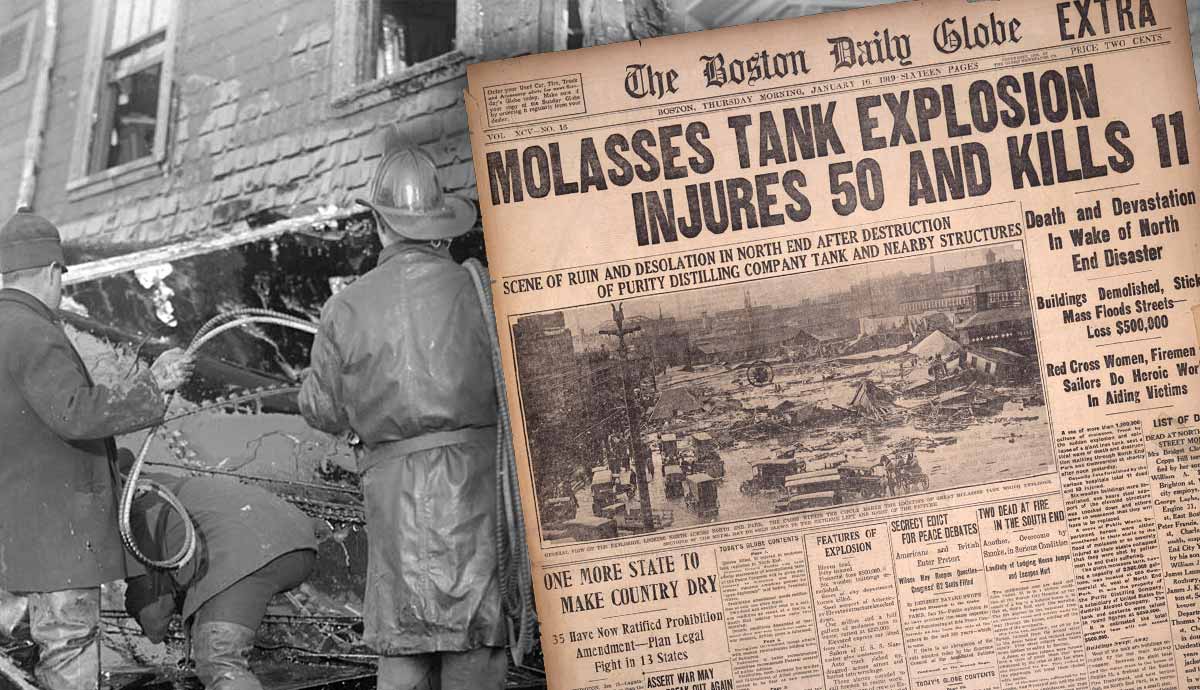

On January 15, 1919, a warmer-than-usual day, the full tank exploded. The tank, the largest of all molasses tanks in Boston, held 2.3 million gallons of fermenting, sticky, and stinky molasses. As the tank exploded, metal rivets holding it together were torn apart and flew through the air like shrapnel. The force of the explosion was strong enough to collapse some buildings and knock others off their foundations. The vacuum effect created by the explosion dragged a truck across the street and pulled a train car right off the tracks.

Of course, the explosion of the tank meant that molasses would flow. So much molasses. It was effectively a tsunami approximately 30 feet tall rushing down Boston’s Commercial Street at 35 miles per hour. The liquid in the tank was warmer than the outside air. When it spilled out, it quickly cooled and thickened. And as it spread, it created a two-to-three-foot-thick layer across much of the downtown harbor area. And due to its thick and sticky nature, it buried and drowned many people and animals nearby. While over 150 people were injured, 21 unfortunately lost their lives, along with countless cats, dogs, and horses. The flood was devastating for the harbor community. Many rescuers- police, fireman, red cross volunteers, and helpful citizens quickly became stuck and had to be rescued themselves. Rescue efforts continued for four days before clean-up even began.

The Cleanup Effort

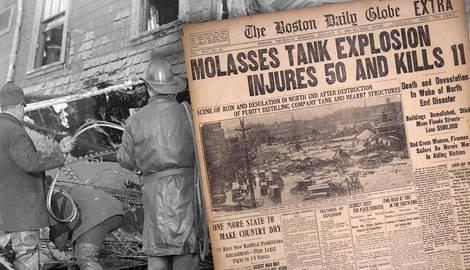

Clean-up took a significant amount of time as the thick, viscous liquid was compared to quicksand. It was difficult to cut through the mess and find victims, survivors, or much of anything else. When the tank had exploded, it was a warm early afternoon in Boston in January. By evening, the temperature had dropped, and so had the molasses, turning into a hardened sugar block. Workers frantically tried to use saws, picks, and chisels to clear chunks of congealed sugar and find bodies within the wreckage.

One body was found 11 days after the spill, while another took over four months to find, eventually being pulled from the water near the Commercial Wharf area. Workers quickly realized that salt water broke down the sugary substance and began spraying the streets with water pumped in from the harbor instead of from fire hydrants. The Engine 31 Fireboat was instrumental in this clean-up effort, even though their firehouse had been destroyed in the molasses flood. After most of the molasses had washed out to sea, the rescuers poured salt and sand throughout the streets in an effort to soak up any remaining molasses residue. Understandably, the streets and building surfaces remained sticky for years to come. The scent of molasses was prevalent on many hot days in Boston when it would begin to ooze from any hiding spots that had not been cleared in the initial clean-up.

Stories emerged of survivors who had lost everything: family members, belongings, and even businesses. George Kakavis, a wholesale fruit retailer on Commercial Street, just across from the tank location, had a cigar box stuffed with $4400 originally hidden in his basement under bunches of fruit that became buried. It was recovered later in almost 12 feet of debris from the explosion.

Lessons Learned

The immediate blame was placed on the US Industrial Alcohol company. But just hours after the tank burst, their lawyers were pushing anti-Italian sentiments and blaming the explosion on Italian anarchists. Since the area around the tank and the harbor was teeming with poor Italian immigrants, powerless against the big company, the US Industrial Alcohol lawyers did anything they could do to steer the blame from the owners. The lawyers artfully downplayed the owners of a company who had contracted a financier to construct the tank and disregarded the complaints they had received about the structural stability of the leaking tank.

After the flood, 119 plaintiffs filed a civil lawsuit against the US Industrial Alcohol company. The case was historic in many ways, but mostly as a template for future civil suit cases. This was the first case in which expert witnesses were called to court to testify. Engineers, Architects, metallurgists, and the like were all asked to provide expert opinions on the tank’s structure.

As Stephen Puleo, author of Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, states:

“All the things we now take for granted in the business — that architects need to show their work, that engineers need to sign and seal their plans, that building inspectors need to come out and look at projects — all of that comes about as a result of the great Boston molasses flood case.”

The court case took over five years to complete and ultimately determined that no acts of sabotage had occurred, stating the cause of the explosion was due to structural failure of the tank. The temperature had been 2°F just two days prior to the explosion. The significant warm-up to 40°F in a matter of days increased the pressure within the tank and made the conditions ripe for disaster. The court ruled in favor of the families that had sued, and US Industrial Alcohol was held liable for restitution.

More Floods

The Great Molasses Flood of 1919 is actually not the only strange flood to be recorded.

In 2017, a warehouse collapse resulted in the release of 7.3 million gallons of fruit and vegetable juice owned by Pepsi into the streets of Lebedyan, Russia and the Don River. While no deaths resulted from the spill, there was significant concern for the aquatic life in the Don River. Luckily, no environmental damage occurred.

In Hungary in 2010, a retaining wall holding a waste reservoir gave way, releasing 6.7 million barrels of red caustic sludge. The toxic material moved downhill and into the low-lying villages below. At least ten people died, and more than 100 others were injured when the sludge made contact with them, burning their skin and causing severe eye irritation. Further damage occurred when the sludge moved into local rivers and streams, killing many plants and animals along the way.

Another devastating flood caused by a burst tank occurred in London in 1814. The London Beer Flood, as it was known, occurred due to vats of fermenting porter that burst and resulted in a chain reaction of vats bursting. Between 150,000 and 400,000 gallons of beer were released into the slums of England in an area known as St. Giles rookery. A wave 15 feet high swept through the area. Eight people were killed, and five of those were mourners at a funeral of a two-year-old boy. Due to this disaster, the brewery industry began to phase out wooden vats and replace them with lined concrete vessels.