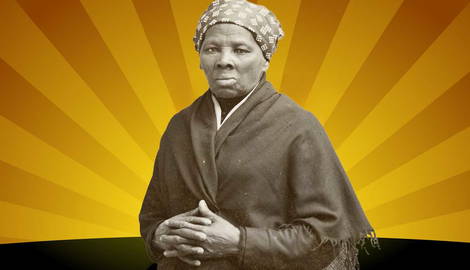

Harriet Tubman was a formerly enslaved woman who escaped and helped many others escape from enslavement. She was one of the most famous conductors who operated on the Underground Railroad. Her service continued into the Civil War with her work as a scout and a spy; even later in life, she cared for the less fortunate. She advocated for women’s suffrage and fought for the equality of African Americans until she passed away and her life is marked by her service to others.

Becoming Harriet

Harriet Tubman was born Araminta Harriet Ross. The details of her birth are not precise, but she was most likely born in March of 1822 in Dorchester County, Maryland, along the state’s east coast. Her mother, Harriet “Rit” Green, was enslaved by Mary Pattison Brodess, and her father, Ben Ross, was enslaved by Anthony Thompson. Her parents’ enslavers eventually married, and “Minty,” as her parents called her, was born as one of nine children in the Ross family. When she was growing up, Harriet was hired out by those who enslaved her to perform tasks for other families. During this time, she learned many outdoor skills, including navigation, that would make her a successful conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Tubman’s early life was troubled and full of strife. Three of her sisters were sold off, breaking apart the family. Rit, Tubman’s mother, did all she could to keep her family together and never again allowed her children to be separated. While her mother and siblings were never set free, her father gained his freedom at 45, when his former master died and willed Ben his liberty. Her father, however, remained on the same plantation as a foreman as he had few other choices.

Harriet endured much physical abuse during her childhood and adolescence. The worst encounter with violence occurred when she was a teenager. Tubman was sent on an errand and, at the store, came across an enslaved man who had escaped from the field. His overseer tried to make Harriet restrain the man, and when she refused, he threw a two-pound metal weight at her, which struck her in the head and caused her neurological problems for the rest of her life. From that attack, she suffered from seizures, headaches, narcoleptic episodes, and intense trances (which she deemed religious experiences) for the rest of her life.

In 1844, Harriet met her first husband, John Tubman, a free Black man. At this time, she changed her first and last names from Araminta Ross to Harriet Tubman, the name she would use for the rest of her life. In 1849, after her owner’s death and her impending sale to another plantation, Harriet and her two brothers escaped north to Philadelphia. Following a posted reward of $100 for each person, Harriet guided her brothers, who were afraid of being captured, home to Maryland before returning to the north. Her husband, John, refused to come with Harriet and married another woman in 1851.

Conductor on the Underground Railroad

Harriet used the Underground Railroad, which had begun in the late 18th century, to flee to Philadelphia. She described the relief when she crossed into Pennsylvania: “When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

However euphoric the feeling of being free was, Harriet was unfulfilled in freedom without those she loved. Thus, in 1850, she began her work of ferrying escaped enslaved people north through the Underground Railroad. Her first trip was to rescue her niece, Kessiah, and her family. Twelve more trips followed the first.

William Still, who provided a “station” on the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia and ushered an approximated 800 enslaved people himself to Canada, was a frequent observer of Harriet’s efforts. In his book, Underground Railroad, published in 1872, he wrote:

Harriet was a woman of no pretensions; indeed, a more ordinary specimen of humanity could hardly be found among the most unfortunate-looking farmhands of the South. Yet, in point of courage, shrewdness, and disinterested exertions to rescue her fellow men by making personal visits to Maryland among the enslaved, she was without her equal.

He recalled her success on the Underground Railroad and hailed her as “wholly devoid of personal fear.” She was reportedly known for her invisibility skill: she could fit in no matter where she went. Her ability to disguise herself helped her become so successful.

Harriet saved most of her family and her friends from enslavement in Maryland. However, she never ventured to other states in the South, nor did she rescue over 300 people, as legend dictates. Her trips to Maryland helped around 70 people escape to freedom. Harriet was a skilled navigator and relied on the stars, the direction of rivers, and other landmarks to guide her across the country. When the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, she upped the stakes of her missions and routed the Underground Railroad into Canada. In her eight years of service, she proudly stated that she never lost a single “passenger” and “never let her train go off track.” Her courage in leading formerly enslaved people to freedom inspired a commitment to serving those around her, and that desire did not change with the outbreak of the Civil War.

Jack of All Trades for the Union Army

Tubman had the makings of an effective spy before she even started working with the Union Army during the Civil War. Her experience as a conductor in the Underground Railroad ensured she could navigate effectively, arrange secret meetings, and remember crucial information. This set of skills went with her when she reported to a Union camp in 1862.

Tubman first worked as a nurse and a cook for the Union, caring for soldiers and civilians from South Carolina. Many of the troops she worked with were escaped enslaved people. However, Harriet found that she could not relate to those in her care: there was a language barrier. The South Carolinians mostly spoke Gullah, a language combining Central and West African languages with English.

Harriet remarked that the people in the camp laughed at her when she spoke and resented her for receiving rations from the army while they barely scraped together any food. To remedy the situation, Harriet began selling pies and root beer to soldiers and civilians and operating a washhouse where she employed civilian workers.

Eventually, under the tutelage of Major General David Hunter, Harriet became a spy and a scout for the Union from Port Royale, South Carolina. She gathered information behind Confederate lines by disguising herself and mingling among enslaved populations. She gleaned Confederate troop movements and information about supply lines.

In 1863, working with Colonel James Montgomery and the 2nd South Carolina Infantry, a company composed of freedmen, Harriet became the first woman to plan and execute a military operation during the American Civil War. On June 22, 1863, Harriet and her comrades attacked several plantations on the Combahee River. Union soldiers gathered supplies and destroyed Confederate property. In addition to attacking plantations, Harriet brought over 750 enslaved people to freedom.

The success and safe passage of the raid was due, in part, to information that Tubman had about mine placement in the Combahee River. She was the only woman in the Civil War to lead an armed expedition into Confederate territory. Confederate memos conceded that someone on the raid must have had exceptional familiarity and skill with the river and area.

Harriet participated in other attacks and operations with the Union army, although not much is known about these later missions. In 1864, a soldier wrote that her services were indispensable to one general, noting that she got more information from newly freed people than anyone else he knew.

Later Life & Legacy of Harriet Tubman

After the Civil War, Harriet Tubman returned to her home in Auburn, New York, which she had purchased from Senator William H. Seward in 1859. There, she lived with scores of family and close friends. In addition to being surrounded by her loved ones, Harriet took in many less fortunate Black people. She provided a home for those society did not wish to take care of: the elderly, the sickly, and the abandoned.

In 1869, Tubman married a second time. Her husband, Nelson Davis, was a formerly enslaved Union Army veteran. He was also more than 20 years Tubman’s junior. In 1874, the couple adopted a daughter named Gertie. The Davises lived comfortably, but they were never wealthy. Harriet spent much of the money she earned on helping others and gave freely without concern for herself.

Tubman’s friends and supporters fundraised to help her along financially. One supporter, Sarah H. Bradford, wrote a biography entitled Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman and gave all the profits to Harriet and her family. Harriet also campaigned for over 30 years for her right to a pension from her time in the military. It wasn’t until her husband’s death in 1888 that she received a widow’s pension of $8, which was then increased to $20 in 1895 in recognition of her service to her country.

Harriet was passionate about many humanitarian causes after the Civil War. She fought for fair treatment of Black people who were sickly or elderly, even donating a part of her property to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, where they built a home for the African American elderly. In 1908, the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged opened to much celebration and pride on the part of Harriet herself. She was also close with leaders of the women’s suffrage movement, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and attended local and national meetings for women’s right to vote.

By 1911, Harriet Tubman moved into the elderly care home on her property after symptoms from the injuries she sustained in her girlhood began to worsen. She died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913, at the age of 93. She was buried with full military honors in Auburn, New York. Surrounded by her friends and family in her final moments, Harriet Tubman’s last words encompassed her life’s purpose: “I go to prepare a place for you.”