In both World Wars, people assume the Allied Powers had a crushing advantage and would have inevitably won the conflicts. World War I, however, was almost a victory for Germany. Far from the American focus on the Atlantic Ocean, Germany had also been fighting Russia, which was an Allied Power along with Britain and France. In March 1918, just as American troops were entering the war in large numbers, Russia left the war, freeing up hundreds of thousands of German soldiers on the Eastern Front. With this boost, Germany almost seized Paris and potentially won World War I. Why did Russia leave the war early, potentially allowing a German victory?

Setting the Stage: Russia Joins Triple Entente

Germany became a unified nation-state in 1871 and scored an unexpectedly rapid victory over France in the Franco-Prussian War. This alarmed the other European powers, who now saw the new Germany as a threat to their security (and imperialist goals). Beginning in the 1890s, Russia’s tsar began aligning Russia with France instead of Germany. Later, it also sought stronger relations with Britain, France’s ally against German expansion. In 1907, Britain and Russia signed agreements, paving the way for a three-way alliance between Britain, France, and Russia.

The goal was to surround Germany and its central European allies of Austria-Hungary and Italy, who had formed the Triple Alliance. With Britain and France situated to the west and Russia situated to the east, the Triple Entente effectively surrounded the Triple Alliance and could strike from either direction. The idea was that the threat of a two-front war would prevent Germany and its allies from attempting hostilities against any member of the Triple Entente.

Setting the Stage: Russian Revolution of 1905

However, Russia was not in a stable place in terms of politics or economics. Despite its vast size, the nation was economically underdeveloped compared to its European counterparts. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 was a humiliation for Russia, which became the first European power to be effectively defeated by an Asian country. In the aftermath of this defeat, the Russian Revolution of 1905 erupted as citizens lost faith in Tsar Nicholas II and his government. People demanded economic and social reforms, believing that Russia’s stagnation had led to its defeat in war.

The revolution was met with force by the government and was unsuccessful at overthrowing the tsar. However, by the end of 1905, the tsar did agree to some reforms, including the creation of a constitutional monarchy. A parliament was established by Nicholas II’s October Manifesto, providing a small degree of democracy. Unfortunately, the economic situation in Russia did not improve much for most citizens, and an undercurrent of anger against the tsar remained.

1914-17: World War I Devastates Russia

World War I erupted in the summer of 1914 after the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Austria-Hungary, allied with Germany, demanded concessions from Serbia, which controlled Bosnia. Serbia was allied with Russia. When Serbia did not meet Austria-Hungary’s demands, a series of war declarations commenced, quickly dragging in all European powers. As a member of the Triple Entente, Russia obligingly mobilized against the Triple Alliance.

While many initially thought the war would be a quick “shoving match” that would re-establish a pecking order, the conflict rapidly devolved into the most brutal and bloody war ever seen. Russia did not perform well in the war and suffered tremendous casualties. Although it mobilized faster than Germany had expected, Russia’s equipment and tactics were less modernized. After the first year of fighting, the Eastern Front bogged down into a terrible stalemate. The Russian economy suffered from the loss of manpower and farmland in the west, swelling citizen unrest.

Russia’s Provisional Government Fails to Make War Gains

By February 1917, many Russians were fed up with Nicholas II’s poor wartime leadership. The February Revolution overthrew the Romanov dynasty and Nicholas II’s government, as massive strikes effectively halted all industry in major cities. Unlike in 1905, soldiers refused to use force against their fellow Russians, and many joined the uprising. On March 2, 1917, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated his throne and was eventually replaced by a provisional government.

The Provisional Government, led by Alexander Kerensky, was created by the Duma (Russia’s parliament) and was forced to share power with a local socialist movement, the Petrograd Soviet. As a result of this power-sharing, little was accomplished under the Provisional Government. Controversially, the government continued the war, and the situation for Russia on the Eastern Front did not improve. A June 1917 offensive against Austria failed, further angering Russian citizens.

April 1917: Germany Sends Lenin Home to Russia

While Russia muddled under the Provisional Government, a Marxist named Vladimir Lenin traveled by train through Germany toward Russia. His goal was to start a communist revolution in his homeland, from which he had been exiled years earlier. Germany, at war with Russia, agreed to help send the exiled leader back, believing that returning a radical to the struggling Russia might lead to internal collapse. On April 23, 1917, Lenin arrived in Petrograd. Would he be accepted…or would the public view him as a traitorous German agent?

Aided by socialists in Western Europe, Lenin’s arrival put him in Russia’s capital, though he was hardly the only socialist in town. The Soviets, or workers’ councils, were full of similar radicals. Lenin’s party, the Bolsheviks, vied for power among other groups, including the Mensheviks. The Bolsheviks were more radical than other groups and wanted an immediate communist revolution. Quickly, the Bolsheviks began to gain popularity among the workers.

October 1917: Lenin Begins Communist Revolution

On October 24, 1917, the Bolsheviks made their move with armed paramilitary units known as the Red Guards. The Red Guards broke into the headquarters of the Provisional Government and dissolved it by force. By this point, the Provisional Government enjoyed virtually no public support. In control of Petrograd, Russia’s winter capital, Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks were now, effectively, the “official” government of Russia.

However, given Russia’s tremendous size, control of Petrograd and the Winter Palace did not mean control of Russia. While millions eagerly supported the Bolsheviks due to ideals of equality for all, many others did not. The Russian Civil War erupted as the Bolsheviks, joined by other communists, fought for control of the country against anti-communist forces. Embroiled in civil war, it was clear that Russia could no longer dedicate any energy or resources to remaining in World War I.

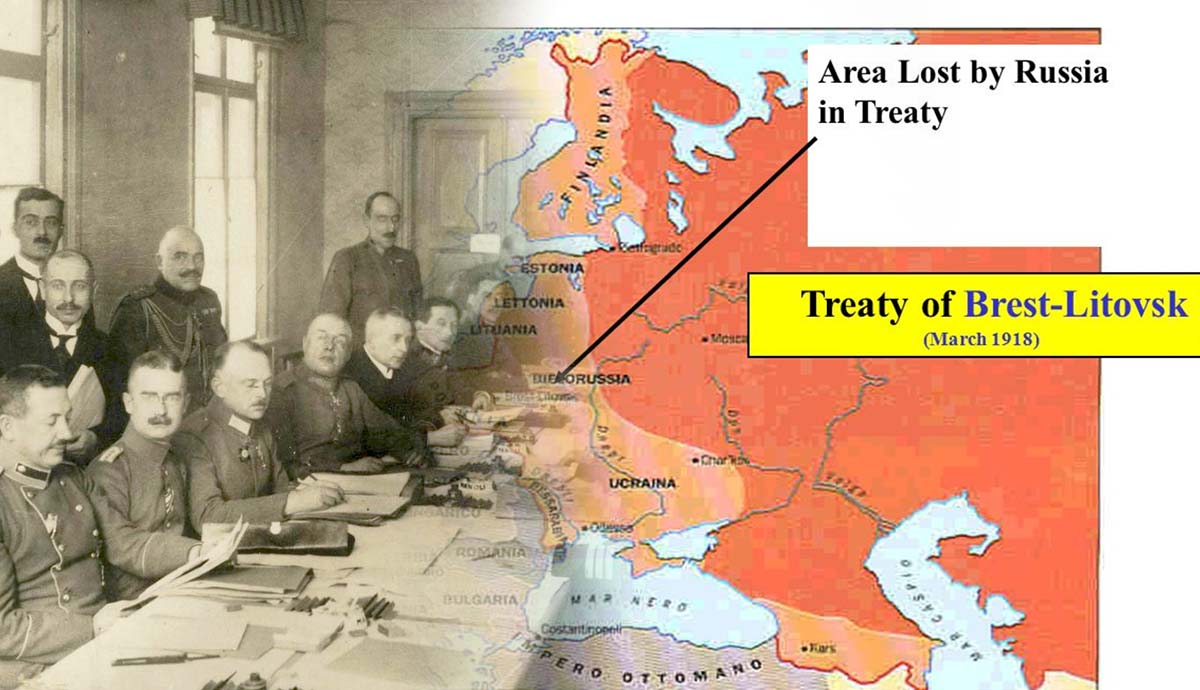

March 5, 1918: Russia Signs Peace Treaty

Immediately upon taking power in Petrograd, Lenin called for an end to Russia’s involvement in World War I. On December 2, 1917, an armistice was signed between Russia and Germany. Three months later, a formal treaty was signed in the town of Brest-Litovsk, ending the war between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire). The Germans received lots of Russian territory, aided by a temporary resumption of fighting in February to frighten the Russians into submission. Lenin accepted the treaty as a way to buy time to win his civil war.

Other communists, however, were outraged by the treaty, which gave away prime western territory to an “imperial power.” Russia lost the modern-day Baltic territories, Finland, most of Poland and Lithuania, and parts of Belarus and Ukraine. Although this ceded land was officially supposed to become independent republics, it was clear that Germany planned to annex or at least dominate them. With consternation, the Allied Powers watched as Russia left the war, freeing up hundreds of thousands of German soldiers on the Eastern Front.

Result: Germany’s Spring Offensive

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk allowed Germany to transfer fifty divisions from the Eastern Front to the Western Front in France. Instead of putting this manpower on defense in the trenches, Germany’s military planners switched to the offensive, planning to use the influx of soldiers to take the war out of the trenches. On March 21, 1918, only weeks after Brest-Litovsk was signed, Germany began its largest offensive of the war on the first day of spring—known as the Spring Offensive.

Sixty divisions pushed west into the Allied lines, spearheaded by specially selected stormtroopers. Although the breakthrough was initially successful, the Allies rallied, aided greatly by the continued influx of American manpower. With the help of the American Expeditionary Forces in France, the Spring Offensive was eventually ground down. The Allies responded with their Hundred Days Offensive, which finally broke the back of the German war machine. In November 1918, Germany asked for an armistice. A year later, the Treaty of Versailles formally ended World War I, punishing Germany harshly with war reparations.

Aftermath: Turmoil in Eastern Europe

The territory ceded by Russia in Brest-Litovsk became new republics right next to the ongoing Russian Civil War. Communists in Russia wanted to re-incorporate these territories into their planned Soviet Union. This included the Soviet-Polish War, which commenced as German troops left Eastern Europe. Between 1919 and 1921, Russian communists attempted to retake Poland, but were ultimately unsuccessful. The communists were successful, however, in seizing Ukraine, which had similarly been vacated by the Germans after Brest-Litovsk.

The Russian Civil War saw a brief period of Allied intervention in the Brest-Litovsk region aimed first at limiting Germany’s ability to capitalize on the new territory and then aiding the “White” anti-communist armies. The small numbers of American and British soldiers ultimately provided little fighting aid to the Whites, who eventually lost the civil war. Still, this Allied intervention greatly strained relations with the new communist government of the Soviet Union. The United States only restored diplomatic relations in 1933, finally accepting the Soviet Union as the legal successor state to Russia.

Aftermath: Distrust of Trading Land for Peace

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded the nation of Poland, created after Brest-Litovsk, and began World War II in Europe. The Soviet Union took advantage of the situation and also invaded Poland, dividing the country. In June 1940, the Soviets also annexed the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The ceded territory from Brest-Litovsk had created small, new republics that could scarcely protect themselves against the two world powers. The easy seizure of this territory also put Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union right next to each other, giving the Germans an easy route to begin Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941.

Since World War II, influenced by both Brest-Litovsk and the Munich Agreement of 1938, nations have largely rejected the idea of trading land for peace—it has rarely worked out well! One example of a (relatively) successful lasting peace requiring a land transfer was the Mexican Cession after the Mexican-American War, which required Mexico to give 55 percent of its territory to the United States! Few nations could afford to give away such vast amounts of land, and Mexico only did so because its northern territory was sparsely populated. Thus, today, nations typically refuse to cede territory in exchange for peace, as seen in the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War.