The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1898 between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain. The peace agreement formally ended the Spanish-American war. It was preceded by powerful uprisings against Spanish rule in Cuba (1995) and the Philippines (1896). Spain’s oppressive means to cease the rebellion created American public sympathy for the Cuban history of struggle. The 3-month war and the Paris Peace Accords made Cuba independent, whereas the United States, intentionally or not, gained territories in the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Thus, the US emerged as a new superpower with overseas territories stretching from the Caribbean to the Pacific.

Spanish-American Relations Before the Treaty of Paris

The Spanish-American war originated from Cuba’s struggle for independence from Spain. Before the popular uprising in 1895, the Cuban independence movement had been fighting against Spanish rule since an unsuccessful Ten Year’s War in 1866-1878. The culmination of the Cuban nationalist revolt was the United States’ intervention, leading to armed conflict between both parties. In 1894, Spain’s cancellation of the trade pact between Cuba and the United States and the imposition of new taxes and restrictions made Cubans economically more vulnerable, thus accelerating earlier struggles of independence in 1895.

The unstable situation and internal conflicts in Cuba threatened the United States’ interests for the following reasons: the geographical proximity of the politically fragile region, and the political set of circumstances which had a spillover effect on the economic environment. By the 1890s, the United States had already invested more than $50 million in the Cuban sugar market, and the annual trade between the ports was nearly $100 million. Cuba’s history of conflict with Spain led to the destruction of sugar mills and related property, damaging United States’ monetary interests in the region.

However, American public outrage in response to the Spanish policy of Reconcentration played a vital role in entering into the conflict with Spain. The above-mentioned oppressive policy implied forcing Cubans into the reconcentration camps with poor sanitation, food, or medical care. Many died from hunger and disease. So-called yellow journalism deserves credit for the growing sentiment and sympathy over the Cubans’ struggle; as part of the marketing, American newspapers reported stories (true or fake) of Cubans’ suffering at the hands of European colonial powers, as had the United States before the Revolutionary War. Hence, the popular demand for American intervention grew dramatically.

The Beginning of the Spanish-American War

To protect Americans and their property in Cuba during the uprising, the battleship USS Maine was deployed to Havana harbor. However, Maine exploded several days after its arrival, killing nearly 300 Americans. Even though Spain denied any involvement in the incident, it was beyond doubt for America that the explosion was a result of Spanish sabotage.

In April 1898, the United States declared war on Spain. In parallel, Congress approved the Teller Amendment, declaring that the United States would offer Cubans freedom from Spain and would not annex the land in the event of a successful operation. To accomplish this goal, the Amendment also authorized the president to deploy military force.

A Splendid Little War

After declaring war, the first military actions took place on May 1st in Manila Bay, where the Spanish naval forces were defeated quite quickly. To Spanish surprise, the United States defended the Philippines, a pacific outstation of the Spanish Empire rebelling against colonial rule. On the other hand, on land, Spain had an advantage at first, as the American military forces were mostly formed by volunteers who appeared to be inadequately equipped for a tropical mission. However, after gaining victory over Spanish army garrisons in Cuba and the US naval blockade of Santiago on July 3rd, a cease-fire agreement was suggested to the McKinley Administration by the French ambassador in Washington, Jules Cambon.

The military actions were referred to as a “splendid little war” by upcoming Secretary of state-John Hay as in just six weeks the United States took control over major colonial properties overseas: Cuba and the Philippines, with a relatively small number of victims. The Spanish-American War officially concluded four months later.

Annexation of Hawaii

The annexation of Hawaii on July 7th, 1898, can be regarded as a manifestation of the United States’ growing colonialism. President McKinley’s administration used the Spanish-American war to take control over the independent state of Hawaii. The sugar trade and economic dependence of Hawaii had been a vital interest of the US. Thus, the reason behind the urge to annex Hawaii was the perceived “threat of Asiatics.”

A great number of Japanese entered the island to work in sugar mills/trade. US political leaders feared that the massive migration of Japanese people would ultimately lead to its annexation by Japan and the creation of the naval base in the Pacific. In addition, the island had a strategic location for establishing a military base and could serve as a central point for protecting the United States’ interest in Asia in the process of international rivalry between the great powers. As a result, on July 7, 1998, a resolution was passed that formally annexed the Hawaiian Islands.

The Treaty of Paris and How It Changed Cuban History

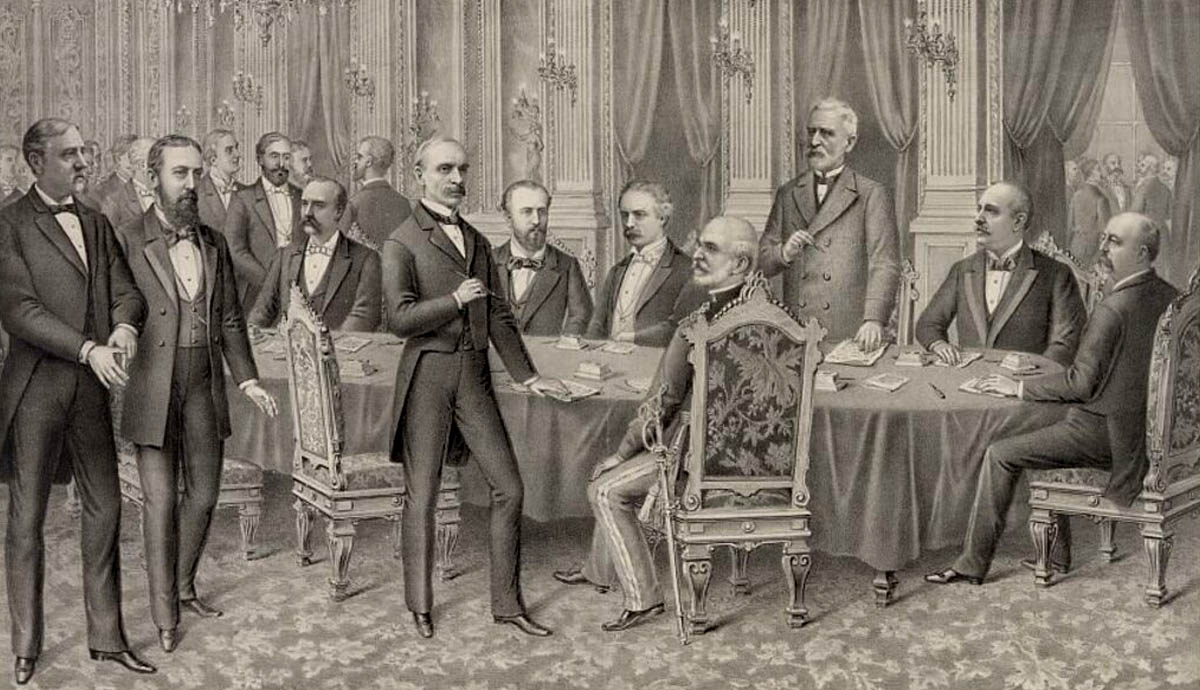

In 1898, representatives of the Spanish Empire and the United States met several times to discuss the terms of the Peace Treaty of Paris that would conclude the Spanish-American War. According to the suggested terms, the military forces of the US would leave Cuban territories. Cuba would be granted independence and freedom as previously promised in the Teller Amendment.

However, the promised freedom was twofold: while the US did not overtly conquer Cuba, it forced Cubans to accept American rule in their new constitution. According to the Platt Amendment, Cuba committed to allowing American diplomatic, economic, and military involvement, as well as leasing Guantánamo Bay to the United States. Secondly, Guam and Puerto Rico, previously possessed by the Spanish Empire, would be granted to the US. Agreeing to the terms of the Treaty of Paris and losing significant territories marked the end of Spanish colonial rule in the western hemisphere.

The only primary point of disagreement between the parties in the Treaty of Paris was the question of the Philippines. Considering the American victory in Manila, President McKinley’s administration refused to simply hand over the islands to Spain, which would be portrayed as a shameful betrayal of the Filipino people.

The Spanish, on the other hand, had a valid objection. The Philippines should have stayed under Spanish rule since the United States had taken control over Manila after the cease-fire was signed on August 12th. Technically, the US should have ceased all military actions. Therefore, the Spanish contended that the United States’ capture of the Philippines was invalid. American diplomats made a deal of $20 million to the Spanish side in return for the Philippines. Spain accepted the offer, leaving the Philippines to yet another rising imperial power- decolonization appeared to be a distant future.

The United States’ diplomats believed that the people of the Philippines – their ”little brown brothers” as the first American Governor-General of the Philippines (1901-1904) and future American president William H. Taft called them – were not educationally and culturally ready to govern the free nation. The term “little brown brother” was an affectionate slur used to justify the colonization of Filipinos, although today, it is an example of paternalistic racism. According to the American vision, Filipinos would need close supervision to develop and resemble Anglo-Saxon political principles.

Secondly, the United States feared that other colonial powers would take over the Philippines, leaving Americans defeated in the new colonial race. Therefore, the Philippines was annexed. In response, the United States had to fight against nationalist forces for nearly two years. In 1901, the rebels were defeated, and the Philippines officially became an American territory.

Finally, The Treaty of Paris was signed on December 8th, 1898. The United States ratified the peace treaty on February 6th, 1899, by a single vote. The documents of ratification were exchanged on April 11th, 1899, between the United States and Spain. The Treaty of Paris entered into force, marking the beginning of the great debate between the imperialist and anti-imperialist powers of the United States.

Consequences of the Treaty of Paris: A Superpower Is Born

The Spanish-American War and the Treaty of Paris were defining moments in both countries’ histories. For Spain, the defeat significantly shifted the nation’s focus away from its overseas colonial endeavors. It resulted in two decades of much-needed economic improvement in Spain and consequently, a cultural and literary renaissance.

After the Spanish-American War and particularly the Treaty of Paris, the outlook of the United States changed dramatically as well. It had been an isolationist nation for over 100 years, industrially developing away from the European colonial powers. With its defeat of the Spanish Empire and acquisition of territories in the Pacific, Caribbean, and Southeast Asia, the United States introduced itself as a prominent actor on the global scene and contributed to the revival of the old Manifest Destiny argument: invoking the idea of the territorial expansion of the United States. The philosophical support is based on the idea that America is destined to expand its democratic institutions, giving the nation a superior moral right to govern territories where others do not respect this objective.

The Treaty of Paris would soon lead to the United States playing a decisive role in the internal and external affairs of Europe and the rest of the world, thus awakening its desire to become a global superpower.