About 1325 BCE, embalmers prepared the prematurely deceased Tutankhamun for burial. They removed vital organs, including his brain, and embedded the body with an extra thick layer of resin. More than three millennia later, twenty-first-century technology peered at his remains to determine answers to his life and death through CAT scans and DNA retrieval. Far from definitive, the scrutiny from technology nevertheless ruled out many previous hypotheses and clarified the struggles and family relationships of the young Egyptian pharaoh.

The Kin of Tutankhamun

In 2005, there were eleven mummies known to be from the Eighteenth Dynasty. Only three were clearly identified: Tutankhamun and his nonroyal great-grandparents, Yuya and Thuya. The identification of major Egyptian pharaohs like the “heretic” Akhenaten and his powerful father, Amenhotep III was uncertain.

DNA was carefully removed from all eleven sets of remains so a family tree could be pieced back together after three thousand years of obscurity. The obscurity was intentional. The next to last gasp of the dynasty, Akhenaten, the father of Tutankhamun, was hated by the priestly noble class and likely by the people themselves, for superseding the long-established polytheistic religion and installing a short-lived monotheism.

Much of Akhenaten’s reign was effaced after his death. The successors even attempted to obliterate Tutankhamun’s reign, despite the return to polytheism that the young king had permitted while he ruled from the ages of nine to nineteen. The result led to the king’s absence from pharaonic lists. Also, it probably accounted for the fact that Tutankhamun’s burial place lay hidden and relatively undisturbed for so long.

Identification provided by the DNA was electrifyingly successful. One of the unknown mummies, in location KV55, turned out to be Akhenaten, the father of Tutankhamun. Tutankhamun’s grandfather, Amenhotep III, inhabited tomb KV35 with his ancestors Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV.

The Mysterious Mother and Daughters of Tutankhamun

According to the genetic study, Tutankhamun’s mother lies in the tomb KV35YL. Labeled the Younger Lady, she is a still unnamed woman who was genetically determined to be the full sister of Akhenaten. Scholars are divided about her true identity. Some claim that she is Nefertiti, but Nefertiti has never been tagged as a sister to Akhenaton nor as the daughter of Amenhotep III. The alternate argument is that KV35YL is not Nefertiti but one of the named daughters of Amenhotep III, none of whom has been listed as one of the wives of Akhenaten. KV35YL remains unknown.

Two small female fetuses, thought to be twins, lay in the tomb with the young king. Both are believed to be still born, one at five months, the other at full-term. The practice of burying stillborn infants in the same tomb as the parents was common in ancient Egypt. Established as the daughters of Tutankhamun, the genetics indicate that they may not be from his queen and sister, Ankhesenpaaten, although the analysis is incomplete due to degradation of the DNA.

Since he was a product of a pattern of incest, perhaps it is unsurprising that this arm of the dynasty ended with Tutankhamun. Incestuous progeny was relatively common due to monarchial concerns but with modern hindsight, it resulted in enhancements of some undesirable traits. Physical issues bedeviled the young pharaoh…

Tutankhamun’s Bones

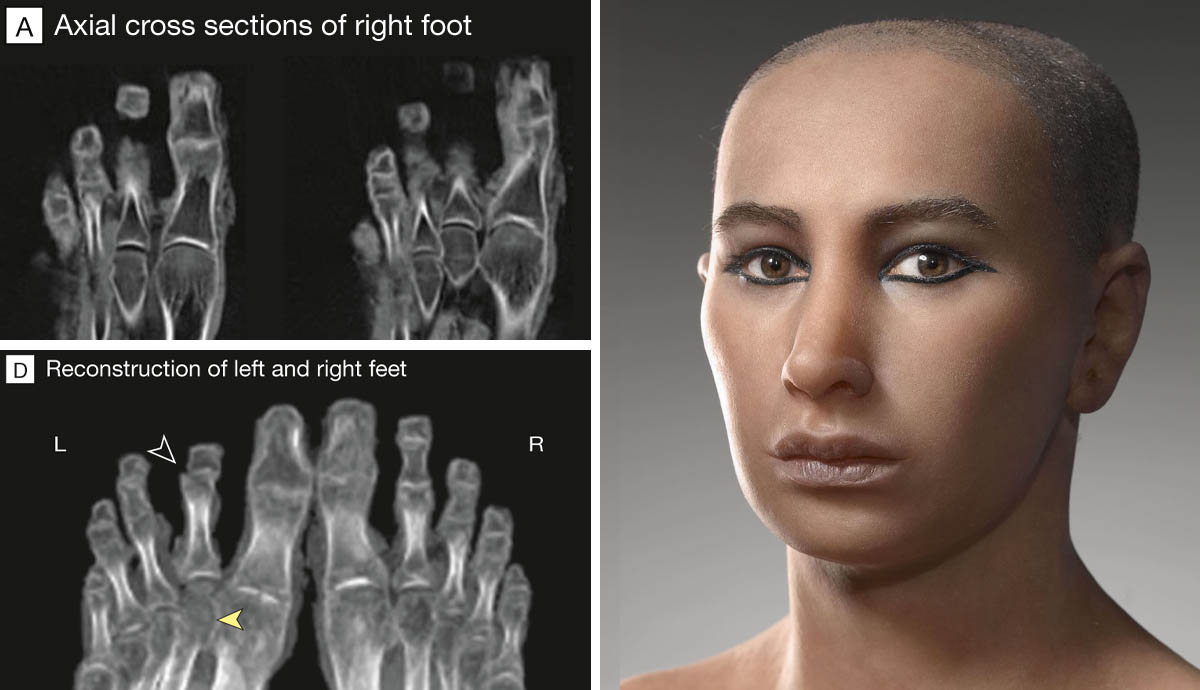

Discovered by CAT scan, King Tut had multiple issues with his feet. He had a clubfoot as did his grandfather and his mother, the foot turning inward, an inherited disorder manifesting itself before birth. Likely even more painful was the bone necrosis of two of his toes. Due to truncation of the blood supply, the bone tissue was starved of oxygen and degraded. Initially, considered a possible symptom of Kohler Disease II or Freiberg-Kohler Syndrome, a rare bone disease, further studies have suggested an even likelier scenario related to malaria.

Several avenues of evidentiary evidence point to a limp. The arch of his right foot was flattened, likely due to the extra weight he needed to place on it and one hundred and thirty canes rested in the tomb with him, some of which were worn with use.

Tutankhamun had mild kyphoscoliosis, a curvature of the spine while Thuya, his great grandmother, had severe kyphoscoliosis. It may not have been noticeable in Tutankhamun but his great grandmother probably had a hunched back. In addition, both Akhenaten and Tutankhamun’s mother had scoliosis, a sideways curvature of the spine, which likewise, may not have been noticeable but builds on evidence of inherited family pathologies.

Finally, the CAT scan showed a severe leg injury to the bone above the left knee. His body had attempted to heal the injury because indications of inflammation were found in the surrounding tissue. The mummy had a multitude of broken bones due to rough treatment after its discovery by Howard Carter, but the break in the leg must have occurred before death, not only from the indication of inflammation, but also because embalming fluid had leaked down into the cracks.

Oral Pathologies

At the time of his death, the teenage Egyptian pharaoh had an impacted wisdom tooth growing sideways in his mouth and undoubtedly was painful. He also had a recessed chin, resulting in an overbite, a genetic condition. Interestingly, his teeth were in especially good condition. He had no cavities nor wear to his teeth, as was common among Egyptian nobility due to the processed carbohydrates and sand that inevitably ended up in the food.

Finally, the young king had a cleft palate, as did his father. The malformation occurs in the sixth and ninth weeks of pregnancy when the tissues from the roof of the mouth fuse. If they do not join accurately, there is a gap in the roof of the mouth. Today, those with uncorrected cleft palates may struggle with certain sounds, developing a nasal sound to their speech. About fifty percent of children with cleft palates need speech therapy, so it is possible that Tutankhamun had a speaking impediment.

Disappearing Hypotheses

So far, there is no indication that the feminization and elongated features depicted in the artwork of the time was due to genetic abnormalities resulting in gynecomastia, an enlargement of male breast tissue, or Marfan’s syndrome which causes long, thin body types and loose joints due to abnormalities of the connective tissue. Klinefelter syndrome was dismissed because the symptoms included infertility which was not an issue.

When the initial research was published, other researchers responded with a flurry of objections, questioning the ability to retrieve uncontaminated DNA as old as the Bronze Age. As time has passed, ancient DNA has been processed from other mummified human remains, so doubts about the possibility of retrieving DNA from ancient mummies may be fading.

Malaria

The DNA unearthed more than kinship relations. The boy had malaria, several strains of the most virulent species. Plasmodium falciparum is a parasite, deposited in the bloodstream by the Anopheles mosquito. Once there, the tiny parasite, a comma-shaped sporozoite, makes a beeline for the liver, arriving in about a half-hour, quick enough to avoid the human immune system. In the liver, it inserts itself into a liver cell and multiplies into forty thousand circular mesozoites. Eventually, they burst out of the liver cell and into the bloodstream to find blood cells in which they hide and multiply some more. Tutankhamun’s DNA analysis picked up gene fragments from the mesozoites. Malaria causes fever, fatigue, anemia and can reoccur in a cyclical manner.

Children, in particular, die from malarial infections, but not always, and communities with a long history of cohabiting with the parasite often build up a degree of immunity, perhaps partly because of a sickle cell mutation. The DNA analysis showed that Tutankhamun’s nonroyal great-grandparents, Thuya and Yuya were also carrying the same strains of malaria and they both lived past fifty, a relatively advanced age for the time.

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited disease that can result in a certain amount of immunity from malaria when only one parent has passed on the gene. In that case, some of the blood cells are sickle-shaped, with a limited ability to transport oxygen, but the mesozoites find it impossible to inhabit the distorted blood cells. Someone with sickle cell anemia can still carry a heavy parasitic load of Plasmodium falciparum. The biggest problem arises when both parents pass on the gene for sickle cell and the red blood cells are severely distorted, sticking together, clogging capillaries, often causing severe anemia and necrosis of bone tissue; exactly what the CAT scan showed in Tutankhamun’s foot. A paper pointing this out suggested looking for genetic markers for sickle cell anemia; and the authors of the original study who have access to the DNA, agreed that the idea held promise, but it is still an open question.

Tutankhamun’s DNA analysis is far from complete. More modern technologies may discover answers that the initial study was unable to confirm: sickle cell anemia, bacteremia, and infectious diseases. The rsearchers looked for, but did not find, genetic markers for bubonic plague, leprosy, tuberculosis, and leishmaniasis. However, blood-borne diseases are most often discovered by analyzing tooth pulp. The authors of the original study mentioned DNA extraction from bone but it is uncertain if teeth were included in that definition.

Portrait of Pharaoh Tutankhamun as a Young Man

As the evidence piles up, the picture of Tutankhamun becomes a little more focused. Akhenaten died in 1334 BCE. Tutankhamun must have been about six or seven years old. A mysterious unknown pharaoh or two reigned for a few years, perhaps Nefertititi under a different name, and then Tutankhamun, at nine years of age, became pharaoh. Despite several depictions of the royal family at Amarna, of Nefertiti and the six daughters, painted on the building stones during his father’s lifetime, Tutankhamun’s likeness or representation with the family seems to be missing. It took DNA analysis and a chiseled inscription on a stone talatat block mentioning Tutankhamun and his sister as the beloved of Akhenaten to attest to the relationship.

Perhaps he was beloved, but Akhenaten may have tried to present a veneer of perfection to his people and the rest of the ancient world in order to prove that he and his queen, Nefertiti, were the blessed conduits of the one true God, the Aten. The art hints at that. It shows a bounty of food, happiness, and light when it is known that food must have been scarce, at least among the people. Perhaps his son and heir, who needed a cane to walk, who struggled with speech, who fell ill so often, was kept out of the limelight and off the painted walls for a reason. If that was the case, despite the grandeur of the burial goods, the remnants of mummified remains of the short-lived boy-pharaoh buried with the tiny corpses of his attempt to continue the dynasty, seem particularly poignant.