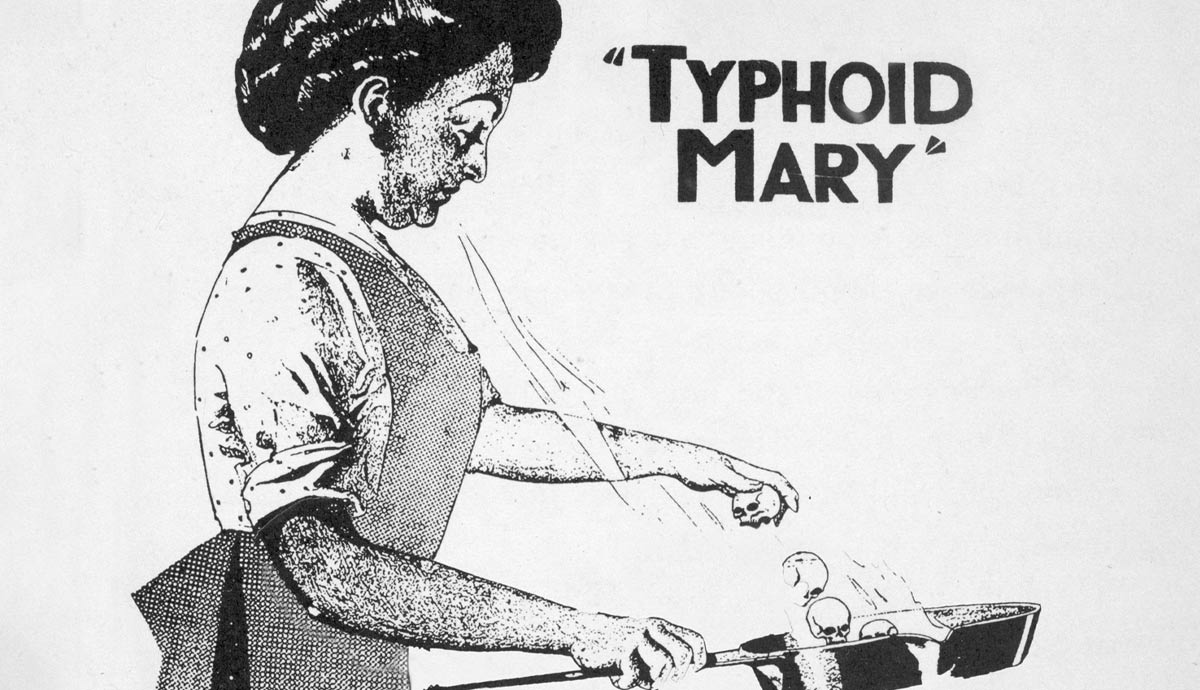

In the 19th century, typhoid fever was just one of many public health concerns doctors struggled to understand. Understanding of sanitation and immunity was still in its infancy, but one case of typhoid shattered existing theories and led to one woman’s notoriety and christening as “Typhoid Mary.” Her life would be changed forever in order to preserve the health and safety of others.

Typhoid Terror

Typhoid fever is a bacterial infection caused by salmonella typhi, spread through food, drink, and water sources contaminated with the bacteria. The illness causes fever, abdominal pain, severe diarrhea, chills, severe fatigue, and even death. It is also known as enteric fever, and today is rare in the United States. However, it still affects millions of people globally each year and is responsible for the death of hundreds of thousands.

Historically, typhoid fever was an even larger threat, more fatal than it is today with the impact of modern medicine. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, doctors had just begun to figure out how typhoid spread and still weren’t fully aware of the disease’s action. At the beginning of the twentieth century, typhoid fever had a fatality rate of approximately 10%.

Mary Mallon’s World

During this time period, Ms. Mary Mallon was building her life in America. Mary emigrated to the United States from Ireland in either 1883 or 1884 as a teenager. She lived in New York and began making a living as a domestic, most frequently as a cook. Mary was a talented cook and popular with her employers, who were generally folks who might hire her to work at their summer homes. Her signature dish was said to be peach ice cream, carefully curated with the freshest peaches.

For several years, starting in 1900, people in the homes where Mary worked began to get sick with typhoid fever. In all, about two dozen people fell ill. However, by the time the disease was traced to a particular household, Mary had moved on to other employment, so she and her meals were never considered to be a common factor in the mini-epidemic.

The Investigation Begins

In 1906, Mary was working in a home of eleven people in Oyster Bay, a popular area for the elite to spend their summers, as President Theodore Roosevelt had declared his home there the “summer White House.” Six individuals in the home became ill with typhoid, and wanting to get to the bottom of the matter, the homeowners contracted George Soper, a sanitary engineer who specialized in tracing disease outbreaks, to locate the origination of the disease in their home.

Little did Soper know, he was about to undertake his most famous investigation. Originally, Soper believed freshwater clams that had been served at the home to be the culprit for the bacterial outbreak. However, further investigation revealed that not all the stricken patients had consumed the clams, and he had to turn his attention to other possibilities. After more research, Soper came up with an interesting theory: Would it be possible for someone to carry the bacteria without actually becoming sick?

A Groundbreaking Conclusion

Soper believed that he was on the way to solving the case. Cook Mary Mallon had not only been contracted at the Oyster Bay home, but her peach ice cream, made from raw, uncooked ingredients, was a common denominator among the sick patients. The first death associated with the Oyster Bay outbreak hastened Soper’s work. Eager to test his theory that Mary may be to blame for the illness, Soper located her in early 1907 and explained to her that she may be spreading disease in her line of work. He asked for samples of her feces, blood, and urine in order to prove his theory. Mary was wholly taken aback by his perceived accusations and requests. She likely felt that he was accusing her of being unsanitary in her food preparation, and the idea of an asymptomatic disease carrier was ludicrous to the average person in early 20th-century America. Mary chased Soper out of her home, furious.

Further Probes

Soper decided to take a different approach and began combing through Mary’s employment records for the past few years. What he found confirmed his ideas that Mary was spreading the typhoid bacteria in her work. Typhoid outbreaks had seemed to follow Mary’s path of employment for years: seven out of eight households had become ill.

He enlisted the help of Dr. Josephine Baker, assistant commissioner of health and one of the most successful early female doctors, to help him deal with Mary. Perhaps a fellow woman could appeal to Mary. This would not be the case, and Mary would avoid the team’s efforts to gather health samples once again. Feeling that the evidence they had gathered proved Mary to be a threat to public health, Soper and Baker once again went to Mary’s home, this time with a police presence.

Unwillingly Quarantined

In March 1907, Mary was detained by Soper’s team and sent to North Brother Island. Located on the East River near the Bronx, North Brother Island was originally constructed as a smallpox quarantine location in the 19th century and was later converted to hold anyone with what was considered a communicable disease.

Mary was not allowed to leave the island in the name of public safety. She was forced to give samples of her bodily fluids, which tested positive for salmonella typhi bacteria. Mary was interviewed repeatedly while on the island to help trace potential and past outbreaks and determine where she may have contracted the disease.

Doctors came to believe that Mary’s mother had contracted the disease while pregnant, and that was how Mary came to be infected. However, Mary never suffered from symptoms of typhoid and just couldn’t wrap her head around the possibility of being a carrier if she wasn’t sick. She refused to believe the accusations of Soper and the other doctors, regardless of what the tests said.

The doctoral team attempted to get Mary to consent to gallbladder removal surgery. It was believed that the offending bacteria colonized the gallbladder and that this removal could potentially prevent Mary’s superspreader status. However, Mary was firmly against this idea, refusing as much invasion of her body as she could. Not to mention, surgery was not a simple undertaking in those days; even routine procedures were potentially deadly.

Mary was not allowed to leave the island but was not officially under arrest or facing any sort of charges. After two years on the island in forced isolation from the world, Mary engaged the services of a lawyer and attempted to invoke the writ of habeas corpus in order to initiate her freedom.

Her bid failed, but it certainly brought more public attention to her case. Her case became of special interest to newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Realizing it was a potential public relations nightmare to keep her locked up against her will, the health department finally agreed to release Mary in 1910 but forced her to agree to never again work as a cook or in a similar capacity, lest she begin spreading typhoid again. She threatened to sue the health department as a result of her treatment but never followed through with a suit. Mary Mallon disappeared back into the crowds of twentieth-century New York.

Free to Infect

It seems that Mary never intended to hold up her end of the bargain. She soon began working as a cook again, a profession she knew she was good at, still not believing she was a health risk. However, she managed to evade the detection of the health department until 1915, when she was found working at a hospital in the midst of a typhoid outbreak. She had been working under an assumed name, and soon, additional recent outbreaks were linked to her past employment. Since she had failed to follow the agreed-upon protocol, the health department again remanded Mary to North Brother Island, where she would remain for the rest of her life. She had a stroke in 1932, leaving her paralyzed until her death six years later.

The Aftermath

Fifty-one cases of typhoid were directly attributed to Mary Mallon during her lifetime, not including those that were indirect or secondary. Three of these cases ended in death, including the first at Oyster Bay. Though some military members were immunized at the turn of the century, effective public vaccination for typhoid would not become available until 1911, and productive antibiotic therapy would not be in place until after World War II. Mary was the first confirmed “healthy” or asymptomatic carrier in the United States. Her plight also highlighted the problematic ways that the healthcare system handled disease carriers and how they were treated by the public, a problem that, in some ways, persists today.

Typhoid Mary: Echoing Questions

The case of Typhoid Mary left many questions, both in an ethical and biological sense, questions that still persist into the modern era. Many people still question the validity of the public health department forcing Mary to stay on North Brother Island for the remainder of her life. There is no doubt that she was a threat to public health, but was it worth ruining her life and forcing her to live in misery?

She was isolated from the world, unable to live how she wished or among people she knew and loved. People also had questions about the idea of an asymptomatic carrier. Mary Mallon had appeared perfectly healthy and did not feel sick. How was it possible for her to be spreading illness and death?

Today, scientists estimate that between 1-6% of those who are infected with salmonella typhi develop into asymptomatic carriers without even knowing it. This is a huge public health risk that is still not fully understood and impossible to monitor. Mary herself was frustrated by her situation and was essentially turned into a monster in the public consciousness when in reality, all she wanted was to be a “good plain cook.”