Many of the world’s most famous artists—like Claude Monet, Salvador Dali, and Pablo Picasso—fall under the umbrella of Modernism, even though their styles vary widely. So, how exactly do we define the Modernist era? Modern art is defined by its rejection of traditional academic standards. While historians debate the exact starting point, the 1863 Salon des Refusés marked a clear break, giving artists new freedom from the Academy’s rigid rules.

Modern Art: Background & Context

When we talk about Modernism, we have to understand the events in art history leading up to it. The first art academies emerged in Italy, starting with the Accademia del Disegno in 1563, founded by Duke Cosimo de Medici I. Its purpose was to codify art as naturalistic, classical, and inspired by sources like mythology or the Bible.

Around 300 years later, the Salon des Refusés was born. An exhibition of artworks rejected from the Academic Salon—which was an annual art event displaying the very best of the best—coincided with a shifting thought in artistic society. Artists began experimenting with styles like Romanticism and Realism, moving away from Renaissance ideals. These shifts eventually coalesced into the broader movement of Modernism.

1. Édouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass, 1863

Before Kandinsky or Duchamp, there was Édouard Manet—often seen as the artist who cracked open the door to Modernism. His Luncheon on the Grass wasn’t just a painting. It was a provocation that sparked a movement. The scene shows two clothed men casually picnicking with a nude woman. She isn’t Venus or a goddess, but a modern-day figure, unidealized, staring directly at the viewer. That blunt realism, combined with rough brushstrokes, flat lighting, and an awkward sense of depth, shocked 19th-century Salon-goers who were used to polished historical scenes.

Rejected by the official Salon, Luncheon on the Grass found its home in the Salon des Refusés. Its inclusion there marked a turning point in art history. Manet had rewired tradition, replacing old myths with modern-day reality. That shift—toward the present, the personal, the provocative—is what made Manet the father of Modern art.

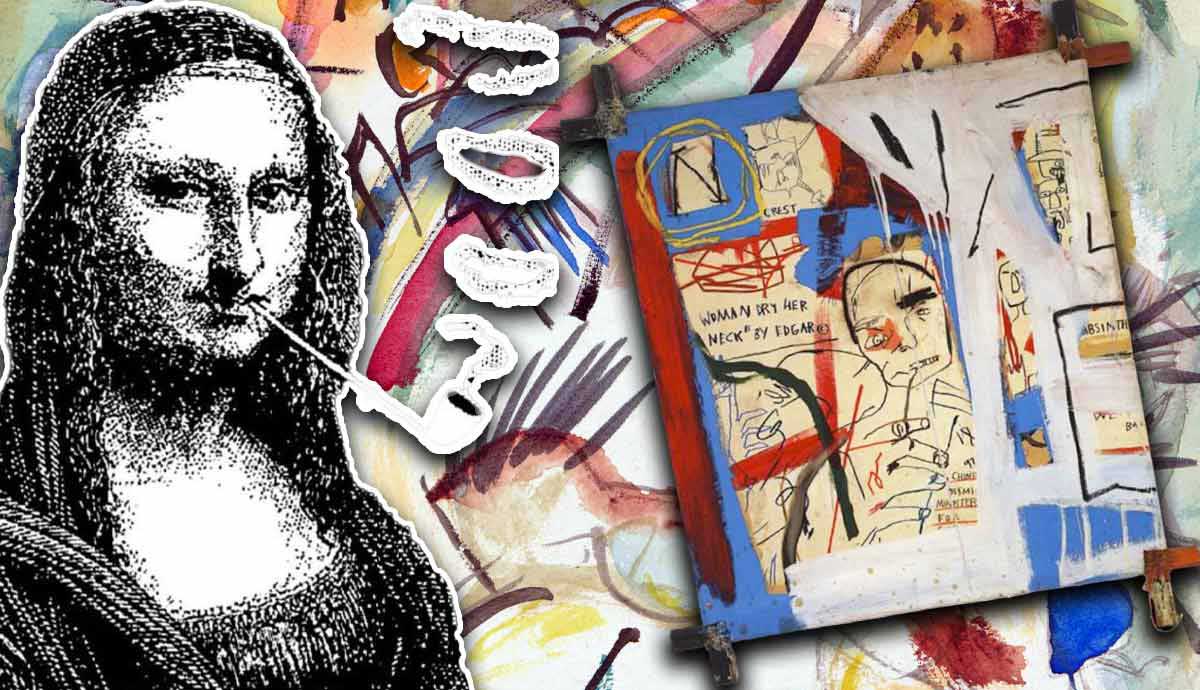

2. Eugène Bataille (Sapeck), Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe, 1887

An early Modern group that headlines the beginning of the period is one called Les Arts Incoherents—French for Incoherent Art. Led by writer Jules Lévy, this group was defined by humor, satire, and accessibility of art, seen in the fact that most of their graphic artworks were cartoons/comics published in widely distributed journals. While most of their works were made in the form of poetry or performance art, some graphic artists were present as well, particularly Eugène Bataille.

Also known under the pseudonym Sapeck, his illustration of Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe for the journal Le Rire remains a virtually unknown piece of Modernism. Here, he draws the all-famed Mona Lisa with one simple addition: a pipe. Satirical images like this are still recreated today. Bataille appropriates the famous Mona Lisa by putting a phallic object in her mouth, poking fun at the renowned status of her and her artist.

Modernism is usually referred to as revolutionary, a title that makes all too much sense for someone like Bataille, living in the aftermath of the French Revolution. As rebellions spread throughout Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, it only made sense that the same ideas would integrate themselves into the art world. The works of the Modern era can even be argued to be a broad act of iconoclasm, defined as the destruction of images. While this term typically refers to the damaging of religious icons (such as the Byzantine Iconoclasm) or political images (seen during the French Revolution), its general idea can be applied to the Modern period. Artists were working to destroy the established concepts of art on a large scale, rejecting everything put in place before them.

3. Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q., 1919

More than anyone or any movement, Duchamp and the Dadaists truly embody what Modernism means. Established in the early 20th century, Dadaism isn’t so different from Les Arts Incoherents. They focus on satire and appropriation, making fun of the elitism of the art world. Ironically, little did they know they’d become a symbol for what we consider elite art today.

Marcel Duchamp was a forerunner of Dadaism, with his most famous work, Fountain. In this piece, Duchamp took a manufactured urinal, flipped it on its side, and submitted it to be exhibited. Fountain created an outrage–if artists can take ready-made objects and call them art, then what does art really even mean? This question was the exact one Duchamp was trying to elicit. But a work even more Modernist than this one is L.H.O.O.Q., another depiction of the Mona Lisa, created 30 years after Sapeck’s rendition.

Here, Duchamp took a postcard of La Gioconda and gave her a mustache and a beard. His joke is exemplified by the title: L.H.O.O.Q., which, with French pronunciation, sounds like Elle a chaud au cul, meaning She has a hot ass. Duchamp, like Bataille, sexualized the artistic icon by commenting on her physical sexuality. In fact, the added beard and mustache can even be seen as symbols of pubic hair around her lips. With commentary on the male gaze, and perhaps even the long-rumored homosexuality of Leonardo da Vinci himself, Duchamp broke away from the art world by criticizing it through one of its most famous components.

4. Wassily Kandinsky, Untitled, 1915

While artists like Bataille and Duchamp lean into the appropriation aspect of Modernism, there’s another important part of the era—abstraction. We typically define abstract art as a deconstruction of the physical form. The first artist that might come to people’s minds is someone like Pablo Picasso and his Cubist pieces, where he broke a form down into all of its elements.

An artist like Wassily Kandinsky took it a step further, though, and turned abstraction into non-representation. That is, the form is so deconstructed that there is hardly anything recognizable anymore. Kandinsky started Der Blaue Reiter group along with Franz Marc, where together they pioneered the German Expressionist movement. An artwork like Untitled (1915) confuses the viewer at first. The first question viewers ask sounds simple, but is deceptively complex: What is Kandinsky trying to show?

In his artworks, it’s not the what that’s important, but the how. Kandinsky is an expressionist who focuses on expressing or conveying emotions. What’s being shown on the canvas gives way to how it’s being shown. Kandinsky does this primarily through his colors. He considered himself a synesthete, so for him, color had sound, typically denoted by a certain instrument. For example, red was aggressive, and as a warm color, it moved out toward the viewer. On the other hand, blue was calming and receding in its cool qualities. Juxtaposing these two together created chaos and disharmony. If you look in the upper corners, you’ll see large splotches of red across from blue, which make the canvas almost tilt in imbalance. Keep this concept in mind when viewing Kandinsky’s works, and their meanings might come a little easier.

5. Willem de Kooning, Woman I, 1950-52

Now, Kandinsky’s Expressionism shouldn’t be confused with the later movement of Abstract Expressionism. Yes, he’s making abstract works in the expressionist style, but these movements are defined separately. One of the largest differences between the two is that Abstract Expressionism took place in the 1940s-50s, in the new art capital of New York City. A trailblazer in this style was the Dutchman Willem de Kooning. Artists like de Kooning were looking back a few decades, inspired by creators like Van Gogh and Munch. De Kooning’s Woman I takes a very traditional European subject—the female nude—and flips it on its head, not in a way entirely dissimilar from Bataille or Duchamp.

The figure depicted in Woman I is grotesque and disturbing, though it is still clear she is a woman through her prominent breasts. De Kooning was appropriating the female form, much like Duchamp or Sapeck did with the Mona Lisa, but on a broader scale. He reduced this woman down to her basic body parts, emphasizing the most important aspect of his movement: abstraction.

His dynamic, dramatic brushstrokes created a similar sense of chaos that Kandinsky depicted in his Untitled work. The colorful palette of pinks and greens gets drowned out by the large swatches of gray that create the woman’s form. We can’t tell if she’s standing or sitting, where her arms or legs are, or if she’s clothed or naked. The disorder of the form reflects the post-war world. Working in the United States, de Kooning and other Abstract Expressionists distanced themselves from European tradition to forge a new, distinctly American art.

6. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Three Quarters of Olympia Minus the Servant, 1982

Modernism informally ended around the 1970s, ushering in a new era of Postmodernism. Artists like Duchamp and Kandinsky became household names. The context of the Cold War flipped the world upside down once again, and artists, doing what artists do, had to modify their works in order to keep up with the times.

This idea is exactly what the early Modernists were trying to do. For example, Manet took the traditional subject of a female nude in his Olympia and unveiled something deeper, something gritty, not unlike what de Kooning did with Woman I. His depiction of a sex worker astounded the Salon-goers in the 1860s, paving the way to the shocking early-Modern artworks of the Impressionists and beyond.

The neo-expressionist Jean-Michel Basquiat did what Duchamp did with L.H.O.O.Q. to Manet’s Olympia: he appropriated her iconic status as a symbol of the Modern art world. In Three Quarters of Olympia Minus the Servant, Basquiat took abstraction to an extreme, breaking apart all forms until everything was virtually unrecognizable.

It’s hard to tell where Olympia is meant to be. There’s some kind of face in the middle, but it looks nothing like Manet’s courtesan. Instead, it more accurately reflects the woman in de Kooning’s work: bald, ugly, and disturbing. Basquiat rejected the mainstreaming of modernism, reshaping its values into something that reflected his experience as a Black artist in New York.

Every artwork he made was an assault on the elitist art world. His graffiti medium portrayed the same idea of accessibility as Les Arts Incoherents did with their journals. Basquiat was painting identity, not just figures and bodies. He was evocative, just like the expressionists, forcing the viewer to analyze and interpret, not just observe.

Modern Art: How Did It Lead Us To Today?

The Modern era allowed artists to experiment and try out new forms, styles, and subjects. Without them, we might still be stuck in the stagnant tradition of academic formality. Imagine if every artwork looked just like a work made by Leonardo or Michelangelo. Sure, they’re beautiful pieces to look at, but doesn’t it get quite boring? Shouldn’t we prefer a wide range of styles, enticing us with each new work we look at?

While Modern art can be hard to get, it’s still important to understand its place within art history. Without Modern artists, we could very well be trapped in the cycle of history without an escape. Their satirical takes on iconic artworks—and their abstract pieces that shattered traditional form—let audiences see something new each time. So, the next time you’re at a museum and feel overwhelmed by the complexity of Picasso or Matisse, remember: artists like them gave the art world freedom. That freedom opened the door to the full range of expression we enjoy today.