From September 1881 to September 1882, Egyptians rose up en masse against foreign powers that had seized control of the country’s financial and political assets.

The main targets in this rebellion were the Anglo-French assets, which were seen as hampering Egypt’s progress and prohibiting it from becoming a successful autonomous nation.

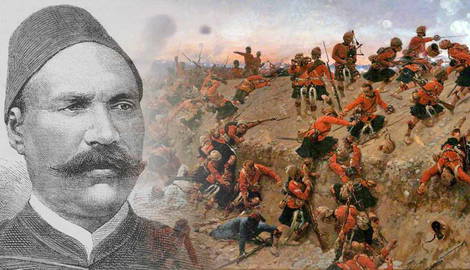

Thus, the ‘Urabi Revolt (sometimes called the Urabi Revolution) erupted, named after its principal leader, Ahmed ‘Urabi. What followed was a bloody enterprise that further extended Britain’s colonial reach but nevertheless represented a step towards Egyptian independence from a Middle Eastern monarchy to a modern nation-state.

Financial Ruin

The road to Egyptian independence was not a straightforward one. In 1805, under the leadership of Mohammed Ali Pasha, Egypt managed to gain de facto independence by declaring autonomy from the Ottoman Empire. After a string of rulers over the next few decades, Isma’il Pasha (nicknamed Isma’il the Magnificent) came to power in 1863 as Khedive (Viceroy) of Egypt and Sudan.

Ismai’l Pasha was the grandson of Mohammed Ali Pasha. He was forward-thinking and made great strides in modernizing Egypt and Sudan. He set to work investing in great infrastructure projects. Internal reforms saw the creation of a sugar industry and the widening of the Egyptian cotton industry. The industries and business opportunities created an influx of European immigrants, and Isma’il Pasha spared no expense in upgrading sections of Cairo and Alexandria, constructing palaces and other lavish buildings.

He built a world-class railway network with 900 miles of track and a massive telegraph network. He also built massive port facilities, harbor works in Alexandria, and thousands of schools nationwide. The biggest enterprise, however, was the Suez Canal, into which considerable sums of money were invested.

He also launched invasions to the south, increasing Egyptian territory into the Darfur region, but failing in a war against Ethiopia.

The result of all these projects and military ventures led Egypt to complete financial ruin. In a few short years, Egypt’s national debt rose from £3 million to £90 million. With an annual revenue of just £8 million, the situation triggered an influx of foreign concern that threatened to overturn the financial order of Egypt.

A small attempt to offset this debt was made when Isma’il Pasha sold Egypt’s shares in the Suez Canal Company. Britain, under the leadership of Benjamin Disraeli, acted fast and scooped these shares up at a bargain in 1875, giving the British considerable power over trade between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean.

International Intervention

After a European committee investigated Egypt’s expenses and concluded that the massive debts could not be paid back, it was decided that the financial affairs of Egypt would have to be delegated to European entities. Britain and France were the main parties interested in taking over Egypt’s financial affairs.

With considerable diplomatic power behind them, France and Britain were able to force Isma’il Pasha into turning Egypt into a constitutional state with a Prime Minister. Nubar Pasha, an Egyptian Armenian, filled this post and became the first Prime Minister of Egypt.

Egypt’s financial situation became even worse as Egypt was still not completely free of the Ottomans and had to provide financial support and troops to aid the Ottomans in their war against Russia at the time.

To add to the woes, there was strong sentiment against foreign influence, especially amongst the military ranks. In 1879, a revolt led by officers in Cairo was a precursor to the larger ‘Urabi Revolt that would start later that year.

Meanwhile, in government, Nubar, who had the support of the foreign powers, did not get on well with Isma’il Pasha, and Nubar resigned. His post was filled by Isma’il’s son Tewfik. This move alarmed the British and the French, especially as the two men attempted to calm sentiments of revolt in the country by announcing plans to ignore debt repayments to foreign powers.

Rebellious sentiment, however, continued to rise unabated and was fueled by more foreign interference in the country. The French wanted to take military action but needed Britain’s support. British attention was centered around dealing with the Boers in South Africa, so they did not immediately respond to the call for military action in Egypt.

A concerted effort by the European powers, headed by Otto von Bismarck, threatened Isma’il Pasha with military action. This spurred the Ottomans to intervene, and they deposed Isma’il Pasha. Tewfik took over the position of Khedive, but this did little to change the situation. They began looking for allies among the Egyptian nationalists. Already leading the charge of Egyptian reform, Ahmed ʻUrabi, a colonel in the Egyptian Army, had garnered much support and had voiced his disapproval of foreign ethnicities, such as Albanians and the Turco-Circassian people who held high-ranking positions in the military.

In a bid to regain control of the military, it was cut in size, and peasants were banned from holding any positions in the army. This raised the ire of the common people of Egypt, and ‘Urabi, who spoke out against this move, became seen as a symbol of hope for the common people.

Tewfik had ‘Urabi imprisoned, but ‘Urabi’s supporters freed him.

‘Urabi Seizes Power

By the Summer of 1881, ‘Urabi’s position was strengthened by a wellspring of support that had become unassailable. When Khedive Tewfik ordered ‘Urabi’s forces to leave Cairo, ‘Urabi refused. Instead, in September, he marched to the palace in Cairo and demanded the creation of an elected government. This demonstration at Abdin Palace on September 9, 1881 is widely regarded as being the beginning of the ‘Urabi Revolt.

The movement was characterized by the slogan, “Egypt for the Egyptians,” a simple statement that vocalized the sentiment behind the ‘Urabists. The slogan can be seen as a nationalist rallying cry, but also one which highlighted the dissatisfaction with the extent of foreign control of the country’s finances, as well as the lowly position Egyptians occupied in their own country.

Tewfik had no choice but to concede to ‘Urabi’s demands, and he began the process, creating a new chamber of deputies, which contained a considerable number of ‘Urabi’s allies. Egypt was now firmly in the hands of nationalists who wanted a complete end to foreign interference. Despite the massive changes, Tewfik was allowed to keep his post as Khedive of Egypt, but most of the power lay in the hands of nationalist officials.

The French and British position was to support the Khedive, and in January 1882, they sent a missive proclaiming the primacy of the Khedive’s position. The Egyptians responded by reforming the government with ‘Urabi as Minister of War.

Violence against ethnic and religious minorities erupted, and Tewfik asked the Ottomans to intervene. The Ottomans, however, were reluctant to send troops against fellow Muslims. ‘Urabi responded to Tewfik’s move by asking the Ottomans to depose the Khedive. The Ottomans refused this request, too.

Violence Turns to War

On June 11, 1882, violence erupted in the city of Alexandria. Foreign businesses were the main target, with the primary victims being Greeks, Italians, and Maltese business owners.

The French and British were prepared and used these riots as an excuse to move naval assets into the Alexandria harbor. Refugees were escorted out of the city via the Mediterranean.

In mid-1882, three American warships were also dispatched in order to evacuate American citizens caught in the violence.

It now became imperative for the European powers to restore order on their own terms. An ultimatum was sent to the garrison at Alexandria, demanding the dismantling of the shore batteries. When this was ignored, the British opened fire on July 11, beginning the Anglo-Egyptian War. The coastal batteries fired back, but the British bombardment was too powerful, and the Egyptian guns were silenced on July 13. The Egyptian defenders were forced to withdraw from the city.

Meanwhile, the French refused to take part in the action and sailed westwards to attack Tunisia. The British House of Commons debated what further action to take, and it was decided that the army would have to be involved.

The first foreigners ashore were the Americans, who sent a party of 70 marines and 47 sailors to occupy the American consulate and patrol the city. They were followed by a force of 3,755 British troops. Their main objective was to advance on Cairo as part of a reconnaissance mission to determine the strength of the Cairo defenses. After an engagement at Kafr-el-Dawwar, it was determined that taking Cairo would be far too costly, as the defenses were significant.

In September, another British force was deployed to the area around the Suez Canal. The British likely feared ‘Urabi would attempt to seize the canal, and thus, it had to be defended.

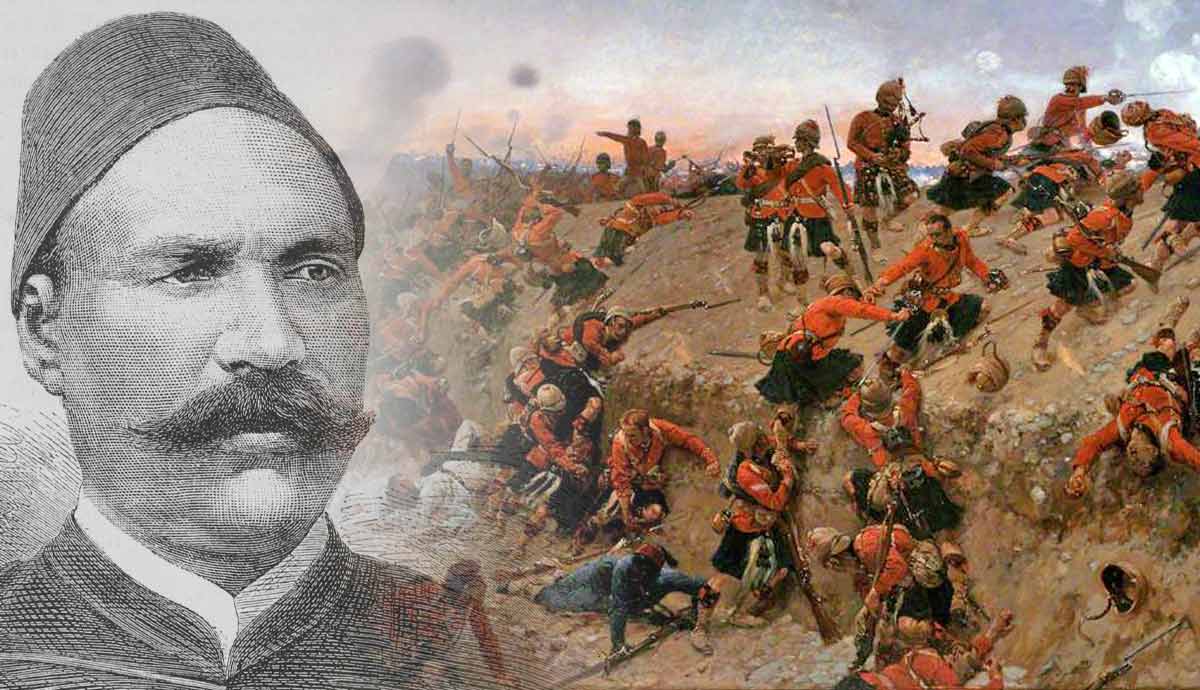

‘Urabi, however, had redeployed his forces northwest of Cairo in a bid to defend the city. Hastily prepared defenses were no match for the British who took the opportunity, and marched under cover of night to engage ‘Urabi’s forces.

The Battle of Tell-el-Kebir followed on September 13 at the break of dawn and lasted under an hour. It was a decisive victory for the British under the command of Garnet Wolseley, and ‘Urabi was captured, thus putting a final end to the ‘Urabi Revolt. The battle resulted in 800 Egyptians killed or wounded, while the British lost 57 dead and 380 wounded. Most of the British casualties were due to sunstroke and not actual combat.

Initially, ‘Urabi was court-martialed and sentenced to death, but the British intervened, and his sentence was commuted to exile to Ceylon (today Sri Lanka).

Tewfik and the position of Khedive were reduced to little more than a figurehead as the British took virtually complete control of Egypt. British societal interest in Egypt became huge as a result, and archeological expeditions gripped the imagination of the British public.

‘Urabi would eventually return to Egypt in 1901, but his arrival did not generate any interest, and he died in relative obscurity on September 21, 1911.

The ‘Urabi Revolt’s Legacy: Conflicting Ideas

Ahmed ‘Urabi’s legacy is a confusing one. While the British painted him as a bloody despot in their propaganda, the reality of the situation was far more complex.

In his article “On Philip Abrams and a Multi-Faceted “Historical Event”: The Urabi Movement

(1879-1882) in Egypt,” Aşık Ozan attempts to delineate the factors underpinning the movement. The political, economic, and cultural factors are all important, and as such, the movement cannot be described within a single unnuanced perspective.

Ozan notes the sentiment of historian Juan Cole, who posits that the ‘Urabi Revolt was a result of an intertwining of class struggle, xenophobia, and religious anti-Christian sentiment.

Historians are divided on the matter, with sentiment being split between the idea that the revolt was a drive for liberal reform and freedom and the idea that it was nothing more than a military coup.

The argument for class struggle is certainly plausible when considering the average Egyptian life at the time. Economic hardships were rife among the Egyptians, especially in the agricultural sector, where most Egyptians worked as poverty-stricken farmers, reduced to the status of peasants.

Many Western authors, such as Jean and Simonne Lacouture, describe the event as a movement of national awakening. If this had not been true at the time, it certainly was viewed by Egyptians thus in the 1950s. Gamal Abdel-Nasser used ‘Urabi as a rallying cry for Egyptian nationalism.

To date, there is no final consensus on what the ‘Urabi Revolt represents, but it is likely a mix of various things for all those who took part. Ahmed ʻUrabi certainly wasn’t the only man involved. He may have led the movement, but thousands of others had their own views of what it represented for them.

With the Battle of Tell El Kebir, the ‘Urabi Revolt and its immediate effects were brought to an end. The revolt, however, had lasting effects that could not be resolved. It had awoken a nationalist sentiment in the hearts of the Egyptians, but it also highlighted the huge inequalities inherent in Egyptian society as well as the cost of foreign interference, and the polarizing effects of an economic system that did not benefit those at the bottom.