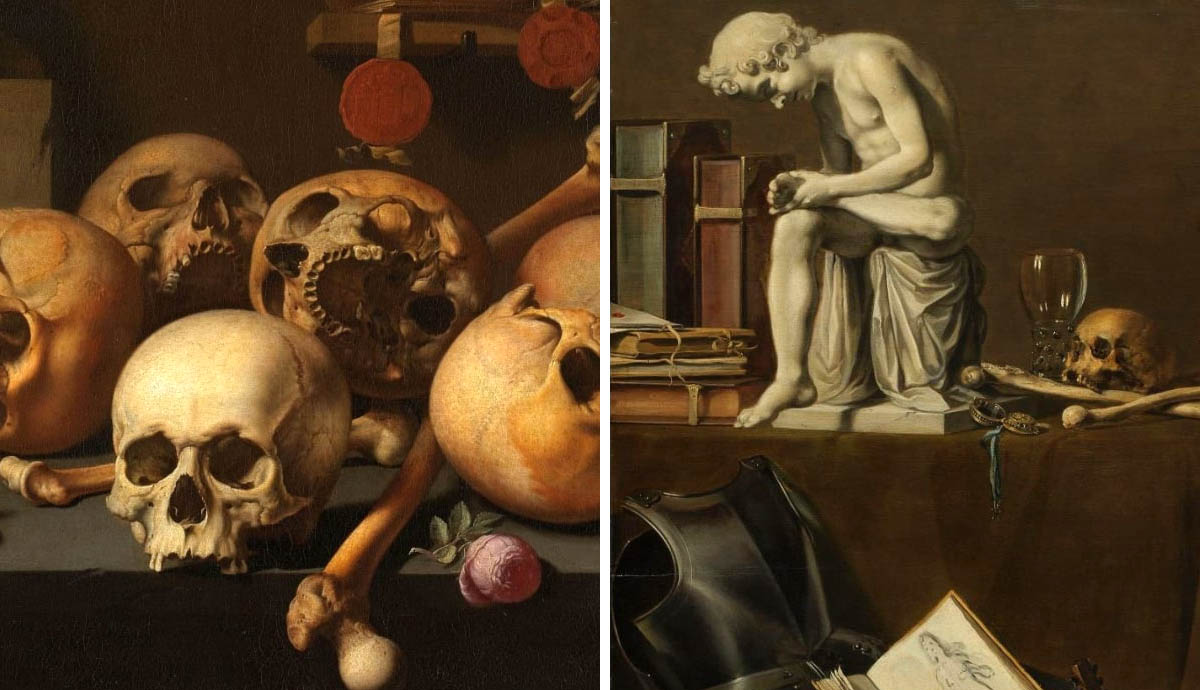

Vanitas paintings are symbolic works of art that illustrate and emphasize the transience of life. Usually, vanitas is recognized by the presence of objects or symbols connected to death and the shortness of life, such as a skull or skeleton, but also musical instruments or candles. The vanitas genre was very popular during the 17th century in Europe. The vanitas theme originates in the Book of Ecclesiastes, which claims everything material is a vanity, and in memento mori, a theme that reminds us of death’s imminence.

Vanitas Paintings as a Genre

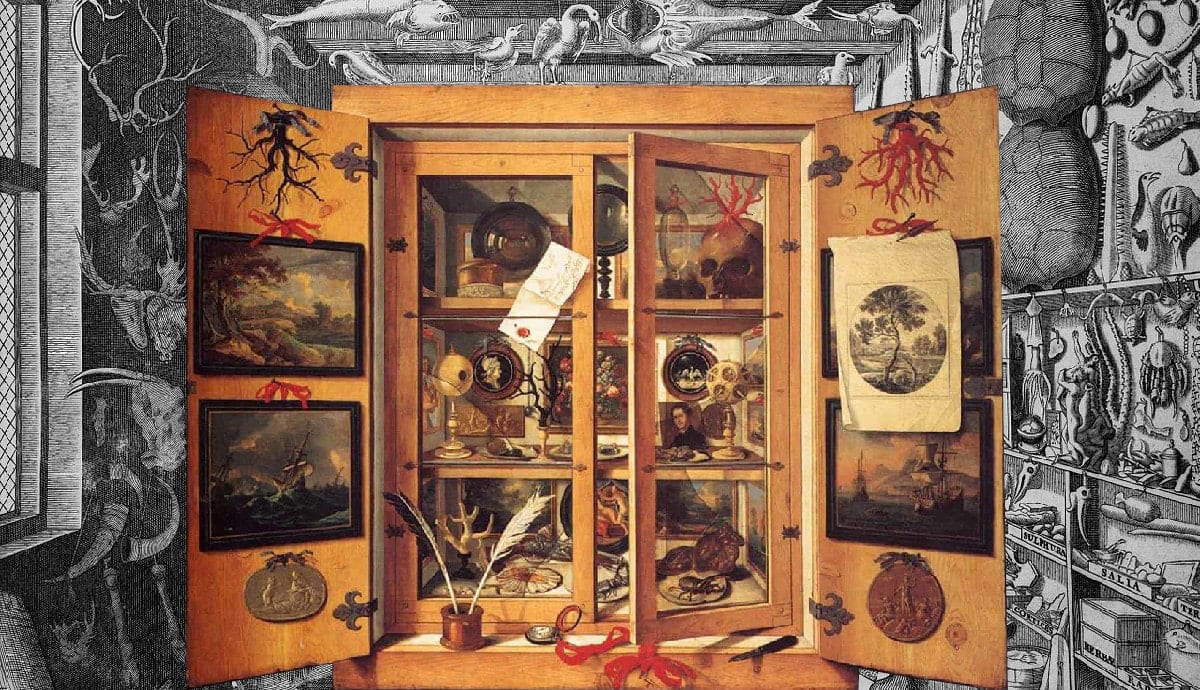

The vanitas genre is usually found in still-life works of art that include various objects and symbols that point to mortality. The preferred medium for this genre tends to be painting as it can imbue the represented image with realism, emphasizing its message. The viewer is usually encouraged to think of mortality and the worthlessness of worldly goods and pleasures. According to the Tate Museum, the term originally comes from the opening lines of the Book of Ecclesiastes in the Bible: “Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities, all is vanity.”

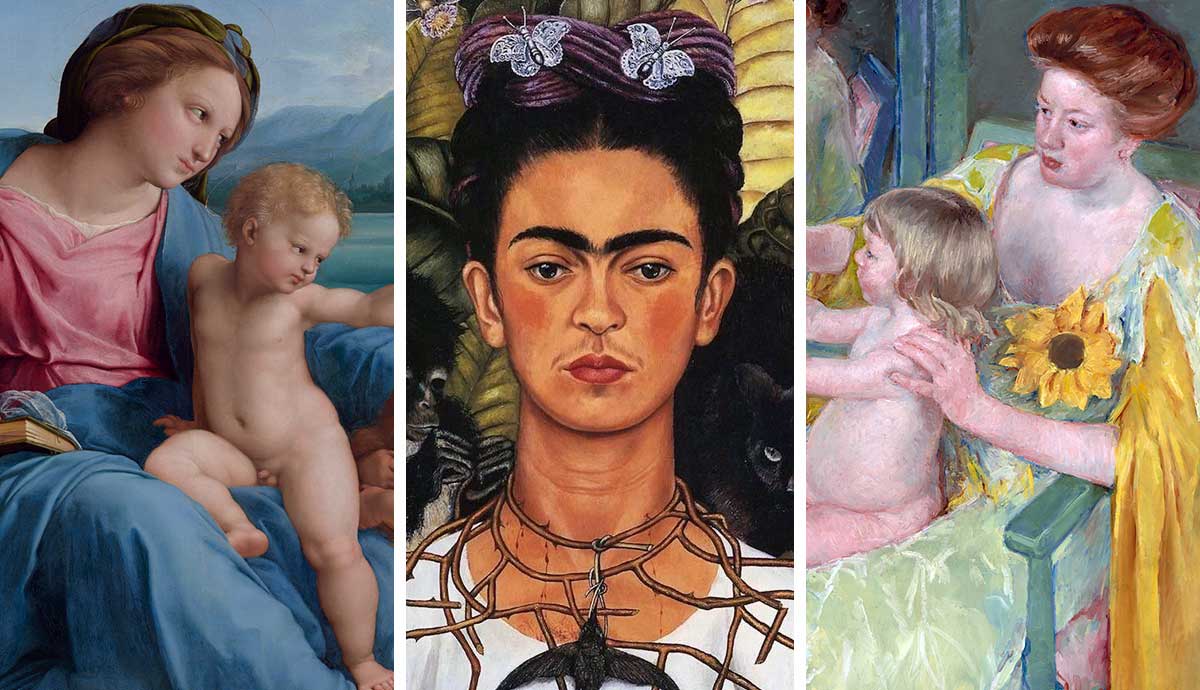

Vanitas is closely related to memento mori still lifes, which are artworks that remind the viewer of the shortness and fragility of life (memento mori is a Latin phrase meaning “remember you must die”) and include symbols such as skulls and extinguished candles. However, vanitas still-lifes also have other symbols such as musical instruments, wine, and books, to remind us explicitly of the vanity (in the sense of worthlessness) of worldly things. These are just a few examples of the objects that make an artwork a vanitas.

What Defines a Vanitas?

The vanitas genre is usually associated with the 17th century Netherlands, as it was most popular in this region. However, the genre enjoyed popularity in other areas, including Spain and Germany. Probably the easiest way to recognize whether an artwork is part of this genre or not is to search for the most common element: a skull. Most of the early modern works that feature a skull or a skeleton can be linked to vanitas because they emphasize the transience of life and the inevitability of death. On the other hand, the vanitas quality of an image may not be so evident in all cases.

Other, more subtle elements can communicate the same message to the viewer. An artist doesn’t have to include a skull to make a painting a vanitas work. Simply featuring a variety of food, some green and fresh while others are beginning to rot, may relay the same memento mori. Musical instruments and bubbles are another favorite metaphor for the shortness and frail character of life. The musician played music, and then it would be gone with no trace, leaving behind just its memory. The same goes for bubbles and, therefore, would perfectly mimic human existence. Any object that is perishable in a visible way can, therefore, be used as a metaphor for the shortness of life and illustrate the fact that all existent things are vanities as they have value only for those who are alive.

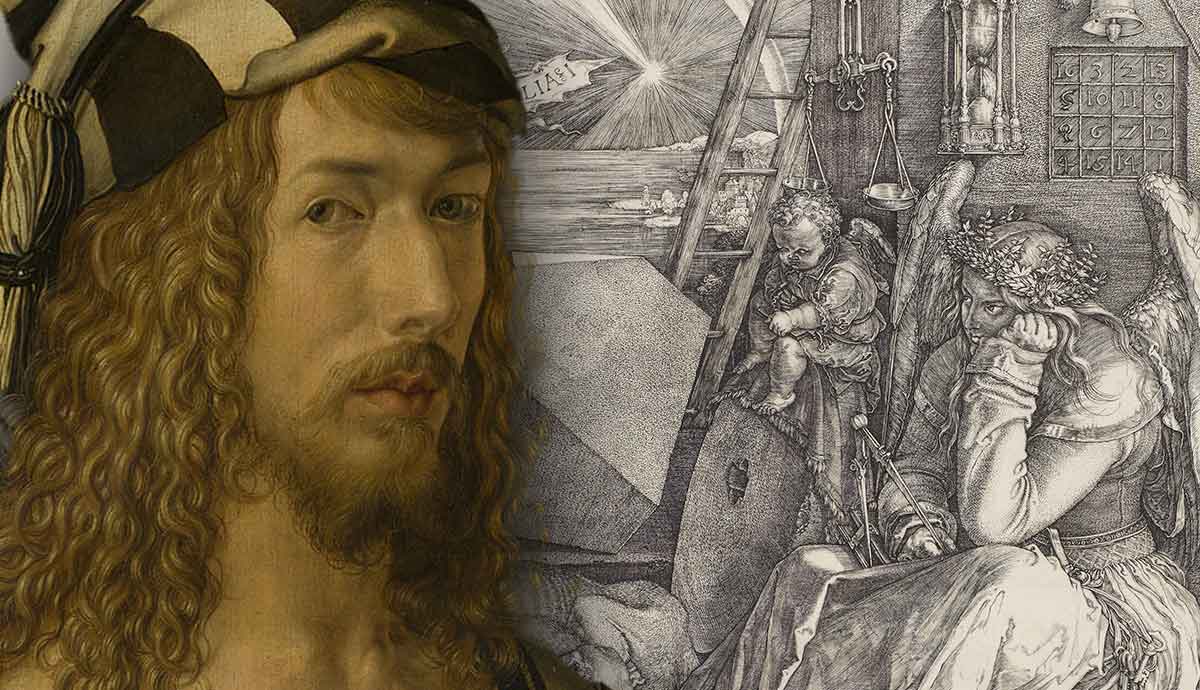

1. German Vanitas Paintings

The vanitas genre has late medieval roots for most Northern and Central Europe. These roots can be found in the theme of Totentanz (death’s dance or danse macabre). The motif of danse macabre is of French origin but became popular in the German cultural space during the late 15th to 16th century. The motif usually shows Death, in the form of a skeleton, dancing with various people of different social statuses. Death is shown dancing with kings, popes, cardinals, warriors, and peasants alike. The message of this scene is the same memento mori and the universality of death.

In most countries where the vanitas genre was popular, the artists who produced vanitas paintings were minor or local artists who didn’t always sign their works. Therefore, a great number of the artworks are anonymous. From the German School of vanitas, it’s good to mention artist Barthel Bruyn, who produced many still-life oil paintings featuring a skull and written verses from the Bible.

However, Vanitas paintings are not necessarily still-lifes, even if this is the dominant trend. A painting could be a vanitas even if it contained human figures or looked like an average portrait. By adding a mirror or a skull, the human figure (usually either young or old) could meditate on the transience of their own life.

2. Spanish Vanitas Paintings

Another place where the vanitas paintings prospered is the Spanish Empire, which was profoundly Catholic and a firm opponent of the Reformation. Because of this, the Spanish Empire engaged in fervent fights during the Thirty Years War and Eighty Years War (1568-1648 and 1618-1648), both of which had a religious component in addition to a political one. Part of the conflicts took place against the provinces of the Netherlands who wanted to gain independence from the Monarchy. Because of this climate, the vanitas evolved slightly differently in Spain.

The Spanish vanitas is visibly connected to Catholicism, having deeply religious motifs and symbols. Even if the theme of the vanitas is fundamentally Christian, as it originates in the Bible, the ways in which this theme is spined, or represented visually, has a lot to do with religious affiliations.

Some well-known artists of the Spanish vanitas include Juan de Valdés Leal and Antonio de Pereda y Salgado. Their still-life paintings have a pronounced vanitas aspect deeply embedded in Catholicism. They often feature the Papal crown and attributes of a monarch, such as a crown, scepter, and the globe. Through this, the artists warn that even the Papal and reigning offices, the highest achievements while alive, are meaningless in death. Crucifixes, crosses, and other religious objects featured in the paintings indicate that one’s hope in regards to death can be placed only in God, as He is the only one who can save us with the promise of an afterlife.

3. French and Italian Vanitas

The French and Italian vanitas are, in a sense, similar to the Spanish style. This similarity is shared through a connection to an artistic vocabulary and knowledge influenced by Catholicism. Even so, the vanitas genre was not nearly as popular in the French regions as it was in the Netherlands. Regardless, a visual style can still be identified for the two regions.

The French vanitas frequently makes use of the image of the skull to assert its vanitas character instead of using more subtle references to the transience of life. However, the religious aspect is sometimes barely noticeable; a cross is discretely placed somewhere in the composition, perhaps. A few good examples of the French style include Philippe de Champaigne and Simon Renard de Saint Andre, both of whom worked during the 17th century.

Like the French style, the Italian vanitas preferred skulls, usually placed in the center of the painting. Sometimes the skull is even placed outside, in a garden among ruins, different from the usual place of the interior of some room. The connection between the skull, nature, and the ruins, bears the same message: humans die, plants bloom and wilt, buildings fall into ruin and disappear. Text is also used to emphasize this message through fitting verses from scripture. The Northern Italian School offers a few surviving examples of vanitas paintings that can be called Italian vanitas. A notable Italian artist is Pierfrancesco Cittadini.

4. Dutch and Flemish Vanitas

As a consequence of the Eighty Years War (1568-1648), the Dutch Republic was formed while the Flemish South stayed under Spanish and Catholic influence. This, of course, affected the art patronage as well. As an effect of the political and religious situation, the Dutch vanitas was influenced by the Calvinist confession, while the Flemish vanitas retained a Catholic tone. In Flanders, the vanitas style was popular but enjoyed the most popularity in the Republic. Even nowadays, people tend to associate the vanitas genre with Dutch works or artists.

In the Dutch Republic, vanitas paintings took on various forms, evolving and bringing the style to its heights. The vanitas gained a more subtle character where the visual emphasis was no longer focused on a skull placed in the middle of the composition. Rather, the message is indicated through everyday objects not normally associated with mortality. Bouquets or arrangements of flowers became a favorite motif to indicate the course of nature, from birth towards death. A person blowing some bubbles became another subtle representation of the vanitas, as bubbles exemplify the frailty of life.

Some notable artists are Pieter Claesz, David Bailly, and Evert Collier. On the other hand, the Flemish vanitas tends to represent symbols of earthly power such as monarchical and papal crowns, military batons, or simply a globe of the Earth to notify the viewer about the naval force of the Spanish. The message is the same: man can rule over others, can be a victorious military commander, can even rule the entire Earth through knowledge and discovery, but he cannot rule over death. Some notable Flemish artists are Clara Peeters, Maria van Oosterwijck, Carstian Luyckx, and Adriaen van Utrecht.

Who Bought Vanitas Paintings?

The vanitas genre had a very diverse clientele. If the genre seems to have been very popular with most citizens in the Dutch Republic, it was enjoyed more by nobles or men of the Church in Spain. By its universal message, the images must have captivated the inherent human curiosity regarding our own death and probably aroused the viewer’s fascination with its representation of complex hyper-realism.

Just like the danse macabre motif seems to have spread across Europe in various forms during the late medieval period and up to the end of the Renaissance, so did the vanitas. As both the 15th century and the 17th century were marked by great disasters, it is no wonder that the general viewer presented an interest in death. The 15th century witnessed the Black Death, while the 17th century witnessed the Thirty and Eighty Years Wars engulf most of Europe. Without question, the place where an abundance of vanitas works was created and sold was the Netherlands.

The vanitas genre was one of the most common genres to be sold in the Dutch art market, making its way into the possession of most Dutch people. Needless to say, a great advantage of Dutch vanitas paintings was the Calvinist confession that matched the memento mori creed. Some perceived the vanitas as a way to morally educate the masses into leading a more conscious and stoic life, aware of the fact that life will end and we will face judgment for our actions.