In ancient Rome, the priestesses of the goddess Vesta were known as the Vestal Virgins. This was an elite group of young women from important Roman families chosen before puberty to join the college of celibate devotees for the next 30 years.

Their existence was seen as essential for protecting the city of Rome itself and ensuring its ongoing prosperity. This gave the Vestals incredible status in Roman society, independent of traditional male power, which was unheard of for women in most parts of the ancient world. However, it also meant that the punishment for breaking a vow was incredibly harsh because it put Rome itself at risk.

1. The Vestals Were an Ancient Order

The Vestal Virgins were one of Rome’s few female priesthoods and, through legend, could trace their roots back to before the founding of Rome itself. According to Roman historical tradition, before the foundation of Rome, the Vestals already existed in the Latin city of Alba Longa. A virgin daughter of the king of that city was forced by a usurper to become a Vestal Virgin.

When women entered the priesthood, they were freed from the patria potestas (patriarchal power) of their family and sworn to chastity. This meant that the princess could no longer pose a threat to the usurper by creating a marriage alliance or giving birth to heirs.

However, according to legend, the gods had other plans. The god Mars impregnated the girl with twin boys, Romulus and Remus, who founded the city of Rome in 753 BCE. Tradition says that it was Romulus’ successor as king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, who built the Temple of Vesta in Rome and established the priesthood of the Vestal Virgins there.

He initially appointed two Vestals to care for the temple, but this number was increased to four by King Servius Tullius, who was also miraculously born of a Vestal, via the god Vulcan, in another pre-Christian example of a virgin birth. Their number was increased to six serving Vestals by the time of the Roman Republic.

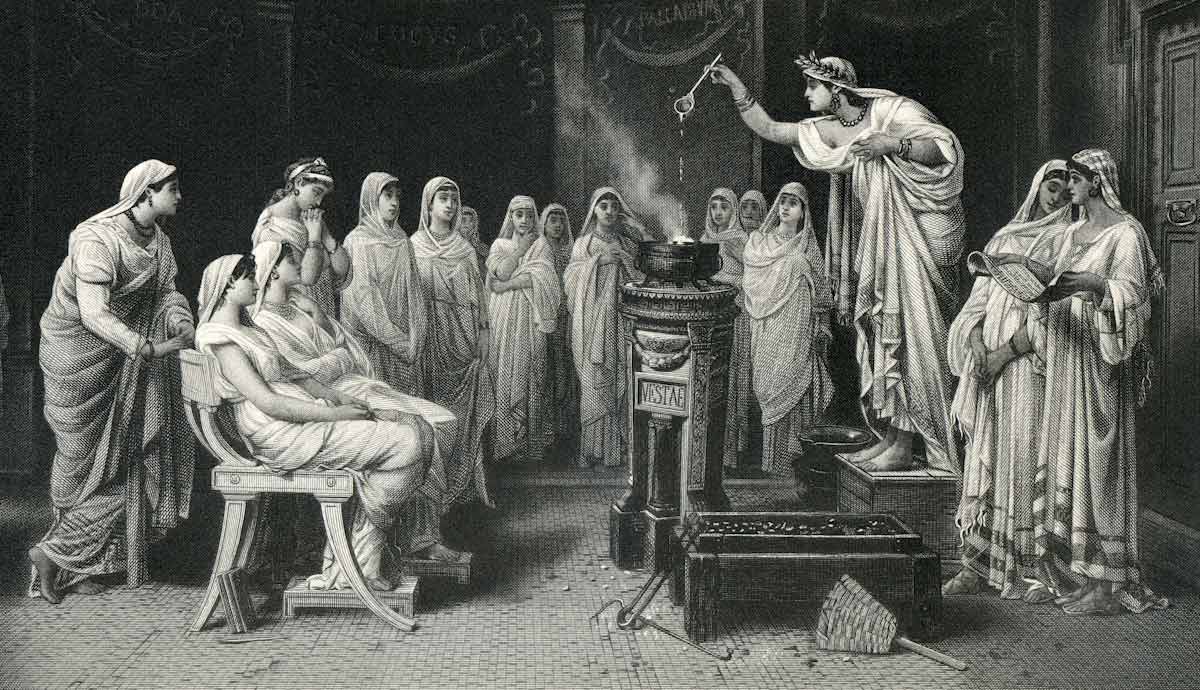

2. The Vestals Nurtured the Sacred Hearth of Rome

Religion in ancient Rome centered around the hearth in each home, where the ancestors of the family (parentes), the guardians of the household (lares familiares), and the guardian spirit of the head of the household (the genius) were worshiped alongside other family and tutelary deities. The Romans believed that they had a reciprocal relationship with their gods and that prosperity depended on proper veneration.

The Temple of Vesta represented the hearth of Rome itself. The most important duty of the Vestal Virgins was to ensure that the hearth always remained lit. If the flame went out, it was seen as a sign that Rome had lost the support of the gods. The population would have to conduct extraordinary religious rites to re-establish their relationship with the gods. If the flame went out due to the negligence of a priestess, she was beaten in penance, and the flame relit through a series of rituals.

Gaius Octavius Caesar, the heir to Julius Caesar, established himself as the first emperor of Rome under the name Augustus in 27 BCE. He was emperor in all but name, using the titles princeps (first among equals) and pater patriae (father of the fatherland) rather than the titles rex (king) or imperator (emperor), which were both vilified in Roman society at the time.

Augustus restored the rights, prestige, and functions of the Vestal Virgins, which had been diminished over the previous decades of civil war. He also gave them his own home to live in, turning over the worship of his household deities to the Vestals. This made Augustus’ household deities also gods of Rome. This was one of the many things that Augustus did to establish his power without taking the title of rex.

3. Vestals Were Buried Alive for Breaking Their Vows

While the most important job of the Vestals was to attend the hearth flame, arguably even more important was maintaining their virginity. When they became a Vestal, their body no longer belonged to them, or their father. They were placed under the authority of the Pontifex Maximus, Rome’s chief priest, and their bodies belonged to Rome itself. As long as their bodies remained unpenetrated, the walls of Rome would remain intact. This also meant that the Vestals could not leave Rome, and they were buried within the confines of the city, which was a great honor not afforded to many men or women.

The bodies of the Vestal Virgins were sacrosanct, and it was considered blasphemy to injure a Vestal. When they moved through the city, they were accompanied by a lictor, a bodyguard who ensured their right of way and could kill anyone who tried to interfere with her.

Having sex with a Vestal was, of course, interfering, so men discovered to have slept with a Vestal were publicly beaten to death by the Pontifex Maximus. The Vestal also had to be punished, but her blood could still not be spilled. Instead, a living tomb was created for her underground within the walls of the city. She was led there and buried alive in a small room with provisions for a few days. She had to appear to go willingly and would soon die “bloodlessly” of “natural causes.”

4. The Vestals Embodied the Maiden, Mother, and Crone

While there were six serving Vestals, the priesthood was much larger. Initiate Vestals were recruited between the ages of six and ten. They had to be the daughter of a free Roman citizen, have two living parents, and have no physical, mental, or moral defects. A long list of candidates was put together by the Pontifex Maximus, and then the girls who would join the order were chosen by lot.

While it was a great honor to have a daughter chosen as a Vestal Virgin, it was also a sacrifice. She was removed from the family and could no longer participate in marriage contracts or give birth to heirs. Initially, only the daughters of patricians (aristocrats) could be chosen, but as fewer patrician fathers were willing to give up their children, the daughters of plebians (commoners) were also chosen. At some points in history, even the daughters of freedmen (ex-slaves) could serve as Vestals.

When they entered the priesthood, the girls swore to give 30 years of their lives to the gods and to remain chaste for those three decades. They spent roughly the first ten years in training, learning how to complete their duties from older Vestals. They would then serve as active Vestals for ten years, before joining the team of older Vestals, responsible for training and leading the younger ones. There was also a chief Vestal Virgin, the Virgo Vestalis Maxima, who was responsible for overseeing the activities of all the priestesses, under the guidance of the Pontifex Maximus.

If a Vestal died in service and a woman of appropriate age needed to be recruited, women could present themselves to the chief Vestal. She would make a choice based on their virtue, but they did not have to be virgins. One such instance occurred in 19 CE, when two senators presented their daughter for selection. The emperor Tiberius consoled the one who missed out by giving her a one million sesterces dowry (about $10 million in today’s money).

5. The Vestals Were Feminine Icons With Masculine Privileges

After their 30 years of service, a Vestal was free to retire. She would retire a wealthy woman with a generous pension from the state. Moreover, unlike most Roman women, she was independent, and not under the authority of her father, oldest male relative, or husband. She could own property, write a will, and even testify in court. This, along with the universal respect that she enjoyed as an ex-Vestal, made her a woman apart.

Once she retired, a Vestal was also free to marry, but there is little evidence that any of them did. Having lived as an independent woman for the last 30 years, making herself the property of a man was probably not an attractive prospect. Many Vestals instead chose to renew their vows of chastity.

Serving Vestals also had exceptional privileges in Rome. In addition to their bodies being sacrosanct, they received ringside seats at the public games, including gladiatorial contests. They could arrive at these shows in a carpentum, a kind of enclosed chariot like those used by Roman generals when celebrating a triumph.

Vestals also had the power to pardon the convicted. It was famously the Vestals who saved Julius Caesar when Sulla included the ambitious young man in his proscriptions. While many Vestal privileges might seem like simple “trappings” of power, they reflect the respect that these women enjoyed within a strongly militaristic and patriarchal society.

6. The Vestals Were Involved in Lots of Scandals

The history of the Vestal Virgins is not without its controversies. Aside from the multiple claims of immaculate conception, multiple Vestals were also killed for breaking their vows, some because they did and others on trumped-up charges that were politically motivated.

A Vestal called Licinia was supposedly courted by her own kinsman Marcus Licinius Crassus, the richest man in Rome in the 1st century BCE. The pair were later acquitted of any misconduct when it was determined that Crassus was actually after some valuable property that she possessed.

Another Vestal, Rubria, was said to have been assaulted by Emperor Nero, who violated her body and the security of Rome. Is it a coincidence that Rome later suffered a terrible fire, believed to have been started by Nero himself?

But by far the biggest Vestal Virgin scandal we know of was when the Vestal Julia Aquilia Severa, married Elagabalus, emperor in the early 3rd century CE. Whether the two consummated their marriage or it was done as a religious show is unclear.

Elagabalus was a devotee of the Arab-Roman sun god Elagabal and served as a priest in his cult until the death of his cousin, Caracalla, which saw him become emperor at the age of just 14. He promoted the worship of this foreign god in Rome. Julia Aquilia Severa was also a devotee of Elagabal. Their marriage may have been meant as a symbolic union between the sun god and Vesta, making them the two most important gods in Rome.

The pair originally married in 220 CE but separated due to political pressure in 221. Elagabalus then married another woman, Annia Faustina, before divorcing her and returning to live with his Vestal wife. They stayed together until he was assassinated in 222 but had no children. While some sources suggest that Julia Aquilia Severa was forced to marry the mad emperor and violated, gossip of the day also suggested that Elagabalus was gay and more interested in his wife’s chariot driver than his wife. The true story has been lost to the historical tabloids.

7. The Retirement of the Vestals Preceded the Fall of Rome

Like many other Roman priesthoods, the Vestal Virgins began to lose their importance with the widespread conversion to Christianity that officially started with Constantine granting Christianity legal status in 313 CE. In previous centuries, Christianity was viewed as illegal in Rome because it was monotheistic. It wasn’t a problem that some people chose to worship the god of the Jews in this new cult (new cults emerged in Rome all the time), the problem was that they refused to worship the other Roman gods. Since the Romans believed that their prosperity was directly linked to the favor of the gods and depended on their proper worship, this was a serious threat.

But as Christianity spread, it was soon the old priesthoods that lost their importance. Some suggested that this had a detrimental impact on Rome. In the 4th century CE, a Roman urban prefect called Symmachus wrote that he believed that cutting funding to the Vestals had directly led to bad harvests and public famine as they lost the favor of the goddess.

Nevertheless, the college was disbanded in 382 CE, when Emperor Gratian confiscated its funds. Is it a coincidence that not long after this the walls of Rome were violated for the first time in centuries?

In its later history, the Roman Empire was split into two, the Western Empire, governed from Rome (and sometimes other cities), and the Eastern Empire governed from Constantinople. Thus, Rome lost its status as the most important city in the empire. It was also sacked by the Goths in 410 CE, sacked by the Vandals in 455 CE, and the Western Empire officially fell in 476 CE. Was this all because Rome lost the favor of Vesta?