One of the most vexing political questions throughout American history has been the role and importance of the vice president. Originally, the vice president was little more than a backup in case the chief executive was suddenly incapacitated. Since the 1920s, the position has picked up more advisory and administrative powers but still carries little executive authority. Famously, many vice presidents have even disparaged their own position, criticizing its lack of power. Strategically, it is a difficult decision to give up a position as a state governor or US senator to become a vice president with no independent power. But can it be the best stepping stone to the White House itself?

Setting the Stage: Article II of the Constitution

When fifty-five of our nation’s Founding Fathers settled into a closed conference hall in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787, they created a new guiding document for our country. The United States Constitution of 1787 was a drastic departure from the previous Articles of Confederation in its creation of a new position: president. This president would be the chief executive of the nation’s new central government and have tremendous powers (especially for the time). But what if this man were to suddenly be incapacitated while in office?

With some degree of foresight, the framers of the Constitution also included a backup position: vice president. In addition to standing by in case something happened to the president, the vice president also served as the president of the US Senate and would cast a tie-breaking ballot in the event of a perfect tie on a bill or confirmation vote. However, the role of the president of the Senate was largely ceremonial due to its only tangible power being to break a tie. This lack of real power led many vice presidents to gaze longingly at the top job.

The Original Veep-to-President: John Adams

Like the first US president, the nation’s first vice president came pre-installed even before the US Constitution was ratified. In the winter of 1788-89, as states still debated ratifying the Constitution, the Electoral College met for the first time, with each of the 69 attending electors receiving two ballots to use. George Washington received one vote from every elector, automatically granting him the presidency. Each elector could then cast a second ballot, with the candidate receiving the second-most votes becoming vice president. John Adams, a diplomat during the Revolutionary War, received 34 votes, with John Jay and John Hancock also receiving votes.

After serving two terms as president, Washington voluntarily stepped aside in 1796, allowing Adams to run. Adams saw himself as the natural heir to Washington’s seat but was challenged by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. The brief campaign was bitter, with Adams running as a Federalist and Jefferson running as a Democratic-Republican (America’s first two major political parties). Adams narrowly won the election, becoming the first US vice president to become president. Unfortunately for Adams, he was far outshone by his predecessor, George Washington.

1. The First Veep to Outshine the President: Thomas Jefferson in 1800

In 1796, Vice President John Adams won the presidential election and succeeded his chief executive, George Washington, in office. However, under the original Constitution, nobody ran for vice president, and that office was granted to the candidate who won the second-most electoral votes. This meant Thomas Jefferson, who lost the presidential election, was elected vice president. Now, the president and vice president were from different political parties and would not likely work well together. Although the error seems tremendous today, it was overlooked in 1787 because the Constitution did not include political parties, and the central government was intended to be nonpartisan.

Four years later, Adams ran for reelection, and “his” vice president, Thomas Jefferson, ran again too. This time, Jefferson won. For the first time, presidential power was transferred from one political party to another. Fortunately, Federalist leader John Adams did not try to prevent Democratic-Republican Jefferson from taking control of the office of president. The Peaceful Revolution of 1800 revealed that executive power could transition peacefully. Ultimately, Jefferson outshone Adams in the history books thanks to the Louisiana Purchase and his 1776 authoring of the Declaration of Independence. His more statuesque physical appearance did not hurt, either.

1804: 12th Amendment Creates the Running Mate

The animosity between Adams and Jefferson revealed the problem of partisanship when it came to the presidency and vice presidency. In 1803, Congress set out to fix the problem by proposing the Twelfth Amendment to the US Constitution. This amendment declared that electors would cast their two votes separately, once for president and once for vice president. This led to the creation of party tickets: the presidential and vice presidential candidates ran together. Now, if the president became incapacitated in office, a similarly-aligned vice president would finish out the term and prevent a major political disruption.

However, to prevent a presidential ticket from giving too much power to any one state, the amendment also included a provision that implied that both candidates could not be from the same state. This led to a common strategy of balancing the ticket: presidential nominees would select vice presidential nominees, known as running mates, from another region of the country. Historically, a Northern presidential nominee would choose a Southern running mate to help attract Southern votes and vice versa. This remained common until the late 20th century.

1836: Martin Van Buren Is the First Running Mate to Become President

Under the Twelfth Amendment, presidents now effectively chose their vice presidents. This gave presidents a strong incentive to help their vice presidents campaign for the office after them. This paid off for Vice President Martin Van Buren in 1836; he had been explicitly courting the support of President Andrew Jackson and Jackson’s supporters. Jackson’s widespread popularity allowed Van Buren to win many votes by claiming to simply continue his chief executive’s policies. The close relationship between Jackson and Van Buren led to a well-organized campaign in 1836, with Van Buren easily chosen as the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee.

Van Buren won the presidential election easily that November, especially thanks to Jackson’s endorsement. However, Van Buren did not retain that popularity as easily as his predecessor and lost his bid for reelection in 1840. The opposing party, the Whigs, had become well-organized since 1836 and ran a unified campaign with war hero William Henry Harrison. In the end, Van Buren’s single term as president definitely did not outshine his two-term predecessor, Andrew Jackson, a hero of the War of 1812.

2. Second Veep to Outshine: Teddy Roosevelt Becomes Youngest President in 1901

In 1865, US President Abraham Lincoln was tragically assassinated only weeks into his second term. Sixteen years later, President James Garfield was shot by an assassin only weeks into his first term. Twenty years after that, President William McKinley, shortly into his second term, was shot by an anarchist (anti-government) radical. While Lincoln and Garfield had both been replaced by relatively little-renowned vice presidents, McKinley had chosen his 1900 running mate well: Theodore Roosevelt, governor of New York, was a hero from the recent Spanish-American War.

Few vice presidents could have hoped to outshine Abraham Lincoln, and James Garfield was well-liked despite his very short term. William McKinley was no slouch, either, as the president who saw rapid American expansion into the Pacific region. In a rarity, President Roosevelt went on to outshine the twice-winning McKinley by passing many Progressive Era reforms. Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt became famous for breaking up monopolies, regulating food safety, and promoting the naturalist movement that eventually led to the National Park Service. Roosevelt easily won reelection in 1904, then handed the Republican Party reins over to Cabinet Secretary William Howard Taft in 1908.

1945: Harry S. Truman Goes From Little-Known Veep to Big-Time President

Forty years after Teddy Roosevelt won reelection as president, a little-known US senator from Missouri named Harry S. Truman was named vice president by popular incumbent president Franklin D. Roosevelt. As FDR ran for a fourth term in the White House, he wanted a less controversial running mate. Sadly, FDR died only a few months into his fourth term, thrusting new Vice President Truman into the Oval Office while World War II still raged in the Pacific. Not since the assassination of Abraham Lincoln eighty years earlier had such tension immediately engulfed a vice president.

Truman did not outshine FDR, though he likely would have outshone most other chief executives. In rapid succession, Truman presided over the end of World War II, demobilization from the war, aiding wounded allies in Europe, and guiding the nation through the beginning of the Cold War. He fought hard and won an upset victory for reelection in 1948, proving his mettle as a national campaigner. Historians rank Truman very high among US presidents…but not as high as FDR himself.

3. Third Veep to Outshine: Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964

While FDR had died of natural causes in the spring of 1945, a tragic assassination returned to haunt the presidency in November 1963. President John F. Kennedy was shot by a sniper while riding in a convertible in Dallas, Texas, thrusting Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson into the role of chief executive. Fortunately for the Kennedy administration, Johnson was a hard-charging former Senate Majority Leader and knew how to get things done in Congress. The tough-talking Texan was able to push through Kennedy’s proposals on Civil Rights and pass major economic reforms.

Johnson’s quick legislative successes in 1964 and 1965 made him extremely popular. Then, however, the escalating Vietnam War rapidly eroded that popularity. By early 1968, the man who had won a full term by a historic landslide in 1964 was at risk of not winning the Democratic Party’s nomination for president again. In a surprise move, Johnson dropped out of the 1968 presidential campaign and announced that he would not seek reelection. Despite his rapid fall from grace, Johnson’s major reforms of 1964 and 1965 could be considered to outshine the impressive accomplishments of John F. Kennedy (JFK) himself.

4. Fourth Veep to Outshine (in a Negative Light): Richard M. Nixon in 1968

When Johnson chose not to run for reelection in 1968, it threw the Democratic Party into turmoil. This gave an easier path to victory to Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon, who had served as vice president under Dwight D. Eisenhower during the 1950s and narrowly lost the 1960 presidential election to John F. Kennedy in 1960. Nixon avenged his humiliating loss of 1960 (and California gubernatorial loss in 1962) in 1968, handily winning the White House against Johnson’s own vice president, Hubert Humphrey. Nixon governed largely as a moderate but won praise for foreign policy successes: he began drawing down the number of US troops in Vietnam and reopened diplomatic relations with China.

With the US economy strong and peace almost at hand in Vietnam, Nixon easily won reelection in 1972, becoming the first man to win two terms as both vice president and as president. Unfortunately, part of his 1972 landslide victory was due to illegal behavior on account of his campaign. Nixon attempted to cover up this illegal behavior, sparking the infamous Watergate Scandal. The cover-up unraveled, and Nixon resigned in disgrace in August 1974, becoming the first president to do so. Despite this infamy, Nixon’s foreign policy successes often make him outshine the quieter Dwight D. Eisenhower.

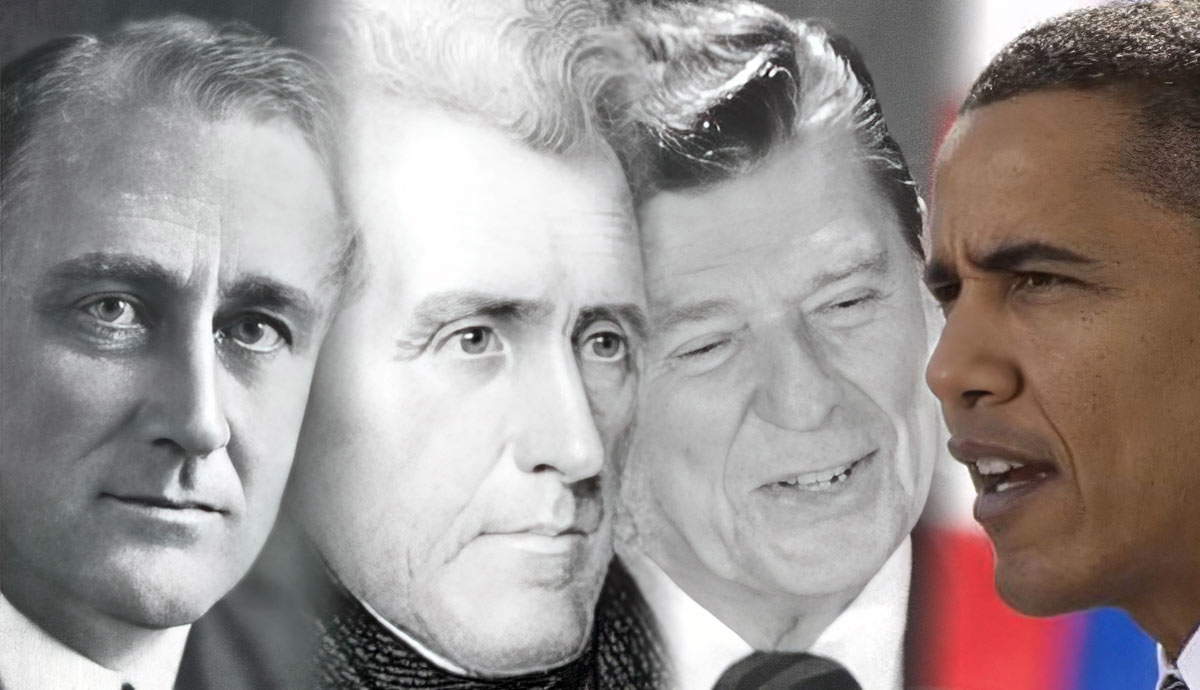

1988 and 2020: Bush and Biden Seen as Continuers, Not Outshiners

The two most recent vice presidents to become president were George Bush Sr. in 1988 and Joe Biden in 2020. Both men had served two terms as vice president, with Bush serving under Ronald Reagan and Biden serving under Barack Obama. However, Bush ran for the presidency and won during his last year as vice president, becoming the first to do so since Martin Van Buren in 1836. Nixon ran in 1960 but was defeated, and all other vice presidents between Bush and Van Buren had been elevated to the Oval Office by the death of the president, not winning an election.

Bush saw his popularity spike in early 1991 when the US won a quick victory in the Gulf War, but this quickly fizzled due to a brief economic recession later that same year. A popular Democratic challenger, Bill Clinton, defeated Bush’s reelection bid in 1992. Despite the Gulf War victory, Bush never got close to outshining his predecessor, who received credit for winning the Cold War. In contrast to Bush, Joe Biden chose not to run for the presidency during his last year as vice president in 2016 and only returned to the campaign trail four years later. Both Bush and Biden are largely seen as continuers of their respective predecessors rather than innovators of their own policies.