In what sense is Nietzsche concerned with virtue? What parallels are there to be drawn between Nietzsche’s conception of ethics and the approach to morality that takes virtue as its essential ethical concept?

This article begins with a discussion of Nietzsche and his admiration for the moral norms and practices of the Ancient Greek world. We then focus on characterizing some Nietzschean virtues, beginning with a discussion of the affirmation of life and the eternal return. Finally, the virtue of honesty or truthfulness will be analyzed, along with the relationship between these virtues and that of artfulness or creativity.

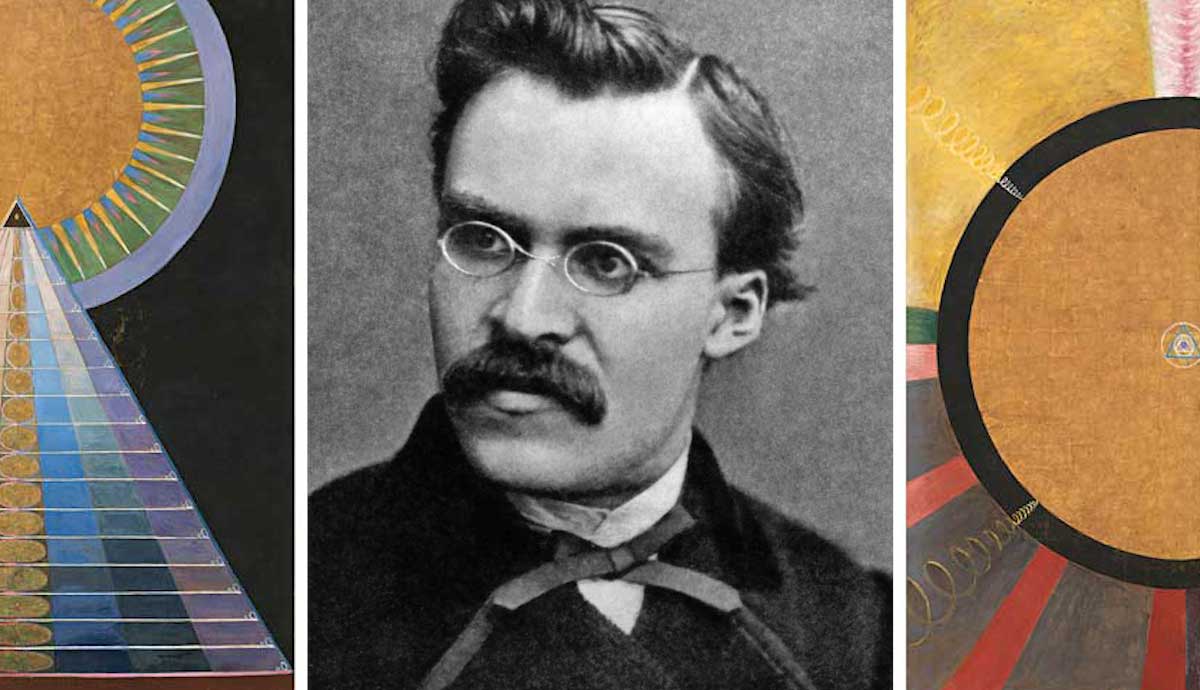

Nietzsche and Virtue Ethics

To explain how Nietzsche is concerned with virtue, it is worth beginning with a word of warning. Nietzsche is not a virtue ethicist in the modern sense. Virtue ethics is an approach to moral philosophy which developed in the latter half of the 20th century and constitutes a modern re-appraisal of the ethical mode of Ancient Greek philosophy.

Nietzsche himself is similarly interested in the morality of the Ancient Mediterranean, but modern virtue ethics (derived from Aristotelian virtue ethics especially) is undoubtedly more concerned with justifying many of our conventional moral precepts in a new way than challenging the most foundational beliefs we have about morality.

Given all of this, what is the relation between Nietzsche’s ethics, and in particular the positive commitments of his moral philosophy, and the concept of virtue? Nietzsche holds the morality of his time as inferior to that of the Ancient World. He identifies a critical shift between the two ethical modes, represented by the move from focusing on kinds of persons to kinds of acts (from a virtue ethical framework to an act-prescriptive one).

Much of what Nietzsche advocates in terms of constructive ethical prescriptions appears to be articulated as virtues. However, the positive element of Nietzsche’s moral philosophy is difficult. Various interpretations abound regarding how far the virtues which Nietzsche describes should be seen as distinctly ethical virtues. It is an open question whether they should be seen as philosophically loaded rather than representative of Nietzsche’s own preferences with respect to human character.

Creating Value

As in contemporary moral philosophy, much of the moral philosophy of Nietzsche’s time (which he took aim at) approaches what is valuable from an ethical point of view as different from—indeed, sometimes wholly in opposition to—what we desire.

The objective element of value relies on the possibility of articulating value in a way that goes beyond whether value prescriptions happen to coincide with what we want. Yet the idea that some part of value might be anything other than what has been made by us is anathema to Nietzsche:

“We [contemplatives] … are those who really continually fashion something that had not been there before: the whole eternally growing world of valuations, colors, accents, perspectives, scales, affirmations, and negations. … Whatever has value in our world now does not have value in itself, according to its nature—nature is always value-less—but has been given value at some time, as a present—and it was we who gave and bestowed it. Only we have created the world that concerns man!”

Nietzsche’s conception of the creation of ethical value can be understood in a variety of ways. It can be understood, on the one hand, as a kind of anti-realism about ethics, a skepticism about the force of ethics. If we invented prevailing ethical norms, why not invent some others? On the other hand, it can be understood as positing ethics as a kind of creative activity, with a force of a new and different kind.

The Affirmation of Life

Having said something about the ambiguous attitude that Nietzsche takes towards constructing an ethical theory in general, we can now consider some of the virtues Nietzsche takes to be most important.

The first of these is that of “affirmation,” and especially the “affirmation of life.” This reflects not just a practice, but an attitude. One of the most famous passages in Nietzsche’s work is,

“I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who make things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: someday I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.”

The extreme radicalism of Nietzsche’s positivity needs to be emphasized here. At another point in The Gay Science, Nietzsche holds that even the erroneous belief that everything which happens to us happens for the best represents an extreme positivity towards life and is, therefore, to a certain extent, recuperated.

This is a kind of anti-social morality, in the sense that it involves ignoring others and focusing exclusively on what one can control oneself. We might wish to note in passing that the structure of the ethical for Nietzsche has nothing to do with holding true beliefs—one might well hold false beliefs which nonetheless reflect the appropriate impulse.

At the end of The Gay Science, Nietzsche’s radical affirmations eventually spill over into the creation of a new, distinct ethical concept—that of the “eternal return.” The eternal return is, in effect, a method by which anyone can assess whether they are living a good life. It requires us to be able to live each moment of our life again, and, in doing so, affirm the choices we made and the experiences we had the first time.

The Eternal Return

The eternal return represents a convenient point at which to turn from the virtue of affirmation to the virtues of honesty or truthfulness. Clearly, this is, in a certain sense, a corrective to the virtue of affirmation, as R. Lanier Anderson points out. There is no point in the affirmation of life if one’s conception of it is, effectively, delusional.

Incidentally, we would do well to observe another parallel between virtue ethics and Nietzschean morality in the requirement of balance between virtues: virtues are never unqualified, but always qualify one another. This principle of the “Golden Mean” goes back to Aristotle.

Honesty is a pre-eminent (perhaps the pre-eminent) virtue for Nietzsche. Much of what Nietzsche says about honesty serves to draw the distinction between his own ethics and public morality:

“I do not want to believe it although it is palpable: the great majority of people lacks an intellectual conscience. … I mean: the great majority of people does not consider it contemptible to believe this or that and live accordingly.”

Questions that remain to be asked of Nietzsche abound. What does it mean to advocate a way of living that the vast majority of people (maybe everyone) falls short of? Does falling short when heading in the right direction constitute victory or defeat, success or failure? How much can be recuperated?

Nietzsche’s Ethical Demands

Just as the virtue of honesty or truthfulness cuts against the virtue of affirmation, so too does the virtue of creativity and artistry cut against it. Art, fiction, aestheticization: these things take on multifarious and seemingly contradictory properties for Nietzsche.

For one thing, our capacity to invent is a way of bearing truthfulness, and therefore, to that extent, supports it:

“If we had not welcomed the arts and invented this kind of cult of the untrue, then the realization of general untruth and mendaciousness that now comes to us through science—the realization that delusion and error are conditions of human knowledge and sensation—would be utterly unbearable.”

Yet at the same time, art is illusion, it is the opposite of truth, and even when Nietzsche appeals to the intrinsic value of aestheticizing our existence, he does not attempt to justify this value in light of honesty. It would be a misreading to say that art, for Nietzsche, represents a kind of honesty or truthfulness, even if there is a measure of honesty and truthfulness in art. In a certain sense, art is the consolation of radical truthfulness: incompatible with it, but necessarily so. The distinction between truth and art represents the apotheosis of the ethical demands in Nietzschean thought.