Political and cultural exchanges between China and Europe have fundamentally shaped modern world history. Although they had no direct contact for more than a thousand years, Europeans and Chinese began to develop ties under the Ming dynasty. The spread of religious concepts and entire traditions was an essential element of European-Chinese contact. Many Chinese were skeptical or even angry about these foreigners’ intentions, but some people did convert to the faith of Jesus Christ. How did these earliest Chinese Christians navigate observing their new religion while staying true to indigenous Chinese customs? How did Chinese Christianity come into existence?

The Origins of Chinese Christianity

The history of Chinese Christianity can be divided into three major phases. The influence of Christian ideas and communities differed in each phase of Chinese history. The third, and final, phase marked the greatest engagement between Christianity and mainstream Chinese culture.

According to archaeological evidence, Christianity first arrived in China in the 8th century. Assyrian Christian missionaries from the Middle East reached China via trade routes, establishing a minor presence. Their influence didn’t last, however. Between persecution by the imperial government and their own low numbers, Assyrian Christians in China had disappeared by the new millennium.

It would not be for several hundred more years that Christians would reestablish themselves in the Chinese spiritual scene. Under the Mongol-controlled Yuan dynasty, European explorers started to visit China with greater frequency. The most famous among these adventurers was Marco Polo, who left a travel narrative behind describing his experiences along the Silk Road in the late 13th century. Yet once again, Christian contact with China did not persist. By the early Ming dynasty, Chinese Christianity had faded away again.

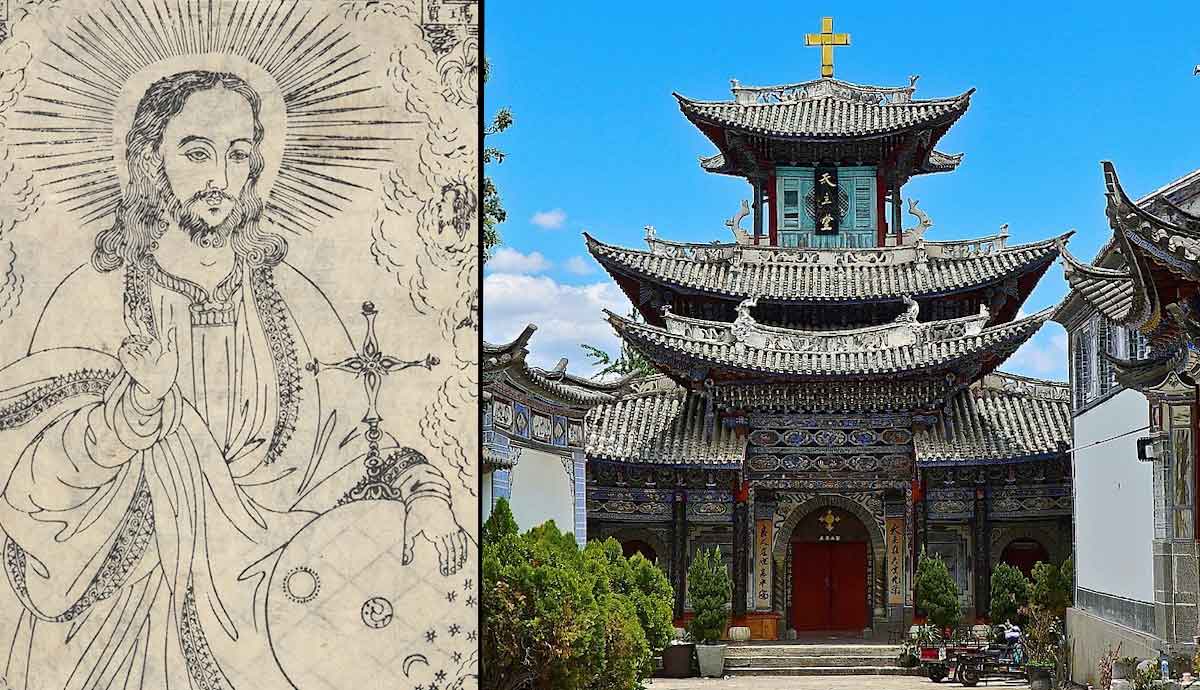

The events of the 16th century, however, would change everything for Chinese Christianity. As Europeans initiated the Age of Expansion, they sought to spread the Christian religion across the globe. The Catholic Church, spearheaded by the Jesuit religious order, led these efforts. In the 1580s, Jesuit priests Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci initiated the first Catholic missions in Chinese lands. From the beginning, they had to strike a delicate balance between staying true to their faith and accommodating Chinese cultural norms. From the Jesuits’ Chinese mission, the first lasting Chinese Christian communities would form.

Uncovering the Voices of China’s First Christians

For those unfamiliar with the Chinese language and Chinese history, uncovering the sources for Chinese Christianity is difficult. But this does not mean that they don’t exist. Due to the Jesuits’ primary focus on converting Chinese elites, some Christian converts left behind written accounts. After all, as the Europeans discovered, China was a highly literate society.

Even though missionaries like Ruggieri and Ricci assimilated crucial aspects of Chinese culture, their efforts proved arduous. The languages of China were unlike any of those in Europe. Chinese cosmological and religious concepts were also fundamentally different from European Christianity. Notably, the Chinese lacked any corresponding notion of prophethood or a single, supreme God, as in Roman Catholicism. How could missionaries hope to succeed in converting Chinese men and women to their strange religion?

Despite the theological chasm between monotheistic Christian thought and Chinese practices, some Chinese were receptive to Catholic teachings. Communities across China converted and sought to uphold their new faith. Modern historians have reconstructed much of the history of Chinese Christianity from this time.

Still, due to the inaccessibility of most primary sources, this article cannot claim to cover everything there is to know about Chinese Christianity. Instead, we will examine the writings of select Chinese Christians to gain a general sense of the spread of Christianity in imperial China. Future studies will be needed to track the development of entire Chinese Christian communities over time.

Xu Guangqi: Polymath and Christian Apologist

The case of mathematician and agriculturist Xu Guangqi is possibly the most well-known. Xu was an early convert to Catholicism and worked with the Jesuits directly on astronomical and translation projects. A friend of Matteo Ricci, he even adopted the Christian name Paul after his baptism.

How did Xu Guangqi conceptualize Chinese Christianity? As his writings show, Xu was both a devoted Catholic and a committed scholar of the Confucian tradition. In his view, Catholic priests and Confucian scholars had the same mission: “to cultivate personal virtue in order to serve the Lord of Heaven” (De Bary and Lufrano, 2000). Their histories may have been different, but Christianity and indigenous Chinese culture were both righteous.

Xu was so devoted to the Christian message that he wrote a memorial directly to the Wanli Emperor in 1616. At the time, authorities in the city of Nanjing had charged Jesuit missionaries with trying to subvert Chinese authority. Xu defended the Europeans and their converts, framing them as “tributary officials” rather than rebellious scoundrels. He pleaded with the emperor to protect the Jesuits and claimed their religion was superior to local Chan Buddhism. Although Xu Guangqi risked his career by defending a foreign religious path, he held to his convictions until his death in 1633.

Li Zhizao: Uniting Confucius and Christ

Li Zhizao was another early Chinese convert to Christianity. He was actually even more educated than Xu Guangqi; Li held the jinshi degree, the highest honor in Chinese civil education. Much like Xu, he worked to explain Catholic doctrine in explicitly Confucian terms. Li’s vision of Chinese Christianity was complementary to the ancient ways of the sages.

In the preface to his work, The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven, Li equated the Chinese Tian (Heaven) with the Christian God. He cites the ancient Classic of Changes to support his view, which speaks of a power in control of the impersonal Heaven. The Christian God Tianzhu (Lord of Heaven) filled this role as the father of the human race. Li’s treatise would soon see publication by a friend, Wang Mengbu, in the city of Hangzhou.

Li sought to tie Christian works to the old Classics. He also held Buddhism in contempt: “The Buddhists… go too far in abandoning their homes and leaving their parents unattended” (De Bary and Lufrano, 2000). With its focus on the divine and family duties, Li held Christianity to be fully in line with Chinese culture.

Yang Guangxian: The Backlash Against Christianity in China

So far, this article has examined the writings and careers of major proponents of Chinese Christianity. However, imperial China was a society committed to harmony and proper social relations. Surely some officials must have feared the rise of foreign teachings? That’s where Yang Guangxian comes in. Unlike the other scholars on this list, Yang Guangxian was never a Christian. In fact, he vehemently opposed Christianity, considering it dangerous. To Yang, the very notion of “Chinese Christianity” was an oxymoron.

Yang started writing in 1659. His writings, compiled in the Budeyi (“I Cannot Do Otherwise”) in 1665, reveal a man well-versed in the moral values of the early Qing-era elite. Yang did not hold back in his criticism of Christianity and its central teachings. He found the Old Testament story of Adam and Eve to be absurd, refusing to believe that “the Qing dynasty [was] nothing but an offshoot of Judea” (De Bary and Lufrano, 2000). Yang’s writing added a coat of xenophobia and ethnocentrism on top of his critique of Christian religious principles.

Most importantly, Yang painted Jesus Christ as a rebellious figure who did not respect the relationships essential to society. By defying both the Roman and Jewish authorities, Yang reasoned, Jesus had specifically broken the relationship between ruler and ruled. To the neo-Confucian scholars of Qing China, this was the ultimate evil. If Chinese converts adhered to the teachings of a rebellious preacher, couldn’t they plot rebellion too?

The End of the Jesuit Missions and the Future of Chinese Christianity

In the early 18th century, Chinese Christianity encountered stiff resistance. Some elite scholars, such as the elderly historian Zhang Xingyao, continued to defend the faith through close readings and comparisons to Confucian teachings. Overall, however, these voices were a minority. The Chinese government had started to turn against European missionaries, fearing potential chaos.

The intra-Catholic conflict over the sincerity of Chinese converts only made the situation worse for Chinese Christianity. The Jesuits and other religious orders argued over whether Chinese ancestor veneration constituted idolatry. By the 1720s, both the Pope and the Chinese Emperor started to crack down. Pope Benedict XIV ended the so-called Chinese Rites Controversy in 1742, marking the final straw for the Jesuits and indigenous Chinese priests. Until the arrival of Protestant preachers in the 19th century, Chinese Christianity almost entirely went underground.