What constitutes a work of philosophy? The boundaries of philosophy are evidently porous and liable to change. Walter Benjamin’s work challenges us not only to redefine those boundaries, but to redefine what it means to participate in some of the main tasks of philosophical inquiry.

Few philosophers can claim to articulate as coherent a vision of the world in such a non-cohesive way. One Way Street is, as Benjamin states explicitly, an attempt to break with literary norms and to articulate himself outside of the boundaries of any existing genre. The effect of this is an extremely eclectic, stylistically varied piece of philosophy, in which Benjamin grounds his worldview in the realm of open-ended creativity – which explains his extensive focus on memory, dreams, and childhood fantasy. This article begins by exploring Benjamin’s flights of fancy, before exploring his vital philosophical conclusions.

Walter Benjamin on Childhood and Memory

Benjamin’s concern with childhood stems, perhaps, from a sense that his childhood is when he felt things deeply, when things had meaning and force in an immediate sense. That adulthood (for material reasons) is now full of the unmotivated, the cold, and the distant makes childhood more forceful and more important. But the importance he ascribes to it is exactly the opposite of the psychoanalyst – Benjamin does not locate the solution to the obscurities of his life in childhood.

In Targets, there is a fantastical, imagined version of a shooting range, in which fantastic things happen – imagination is open-ended and therefore full of irony. It is somewhere between a fairytale and a cautionary tale, full of danger and serendipity.

The Imagination

Imagination, we learn as children, exists in a wasteland. Snow passed through here once; no longer. The floor is frozen solid. Everything moves unevenly without provocation. Things slide past one another.

Immediately following this, we find a contrasting scene of plenty: a marketplace in Riga, modern-day Latvia. Benjamin records the stolid, productive goings on in the town, set before “tall, fortress-like desolate buildings evoking all the terrors of Tsarism.” Another mechanical dreamscape follows, this time taking place at a fair in Lucca. This is a more obvious allegory, and summarizes the kind of theological Marxism Benjamin seems to be developing. The first part of it is described as a kind of Passion Play, while the other evokes elements of the horrors of a capitalist society – “they turn their faces towards each other and then away, as if looking at each other in confused astonishment.”

This feels like a recapitulation of the previous discussion of bourgeois life, and the constant amazement that things are going on as long as they are. On the one hand, it recalls something of Benjamin’s commitment to Marxist materialism – history is determined, set in advance. On the other hand, it is a scene that demands a kind of break.

Benjamin on Criticism

What follows is a related statement of Benjamin’s view on criticism, this time very clearly:

“Fools lament the decay of criticism. For its day is long past. Criticism is a matter of correct distancing. It was at home in a world where perspectives and prospects counted and where it was still possible to take a standpoint. Now things press too closely on human society.”

Much of what Benjamin says in One Way Street rests on a certain kind of idealization of the past, and it isn’t always clear how literally one should take this. Certainly, there is a relative critique of modernity here: things really have gotten worse. This passage is particularly depressing. Benjamin claims that the power of advertisement is such that it is now the “most real” gaze, and the “paid critic, manipulating paintings in the dealer’s exhibition room, knows more important if not better things about them than the art lover viewing them in the showroom. The power of advertisement is not shallow – their superiority is not in the “moving red neon sign – but the fiery pool reflecting it in the asphalt.”

Commercial Life

Benjamin provides a study in bourgeois life – the orientation of everything toward the smooth functioning of business. Comfort becomes a kind of weapon of business, and everything – absolutely everything – is tilted towards commercial functions.

Then follows an observation about the risks of eating alone – the possibility of coarseness, of things generally going awry unless one learns a lesson from the hermit and is frugal. Even in the most throwaway passages, Benjamin seems to express a certain fascination with several forms of life – the hermit among them. Another theme that emerges in this passage is the role of the convivial, of social warmth: “food must be divided and distributed if it is to be well received.”

There is then an extensive discussion of stamps, or more specifically, postage marks – the residue of a stamp that has been sent. Benjamin holds us in thrall to the world of information, the imprint of communication of the most extensive kind, the conception of which is always and ultimately an imaginative exercise. However, he ends with a warning – that this seed planted in the 19th century “will not survive the twentieth.” Intermediate modernity (that required the creation of the world of stamps or stamp marks) is now swinging the other way.

Benjamin’s Method

“Nothing is poorer than a truth expressed as it was thought…truth wants to be startled abruptly, at one stroke, from her self immersion”. Here Benjamin is telling us something about his methodology, and part of the reflections which follow from this shed some light on Benjamin’s association of writing with virility, muscularity, strength, masculine virtue, the heroic (though he takes pains to ‘she’ the writer) – these virtues are what is required to withstand the startling truth.

“The killing of a criminal can be moral – but never its legitimation.” Legitimation here implies something like legal warrant, or at least something close to that (a lawlike ethical legitimation, for instance), and so this expresses a kind of anarchist sentiment.

Reflections on money follow, in which Benjamin draws the relationship between money and time. He observes that the more “trivial the content of a lifetime, the more fragmented, multifarious, and disparate are its moments.” Money atomizes a life and breaks it down into seconds – “life will have to be counted in seconds, if it is to number a respectable sum.” All of this is framed by the preceding observation, that “there is a cloudless realm of perfect goods on which no money falls.”

Beyond Economic Life

This awakens us to the possibility of life beyond the commercial. And yet it is the commercial realm’s ability to construct its own reality that is emphasized here – the satirical possibilities presented by a book about bank notes is matched “only by its objectivity.”

What follows is a brief scene that focuses on money in a different way: it is the dialogue between a publisher haranguing a writer for his lack of commercial success. The punchline; “do not feign innocence when you have gambled everything away” – that is, do not pretend you are an honest businessman, one who only means to help his writers.

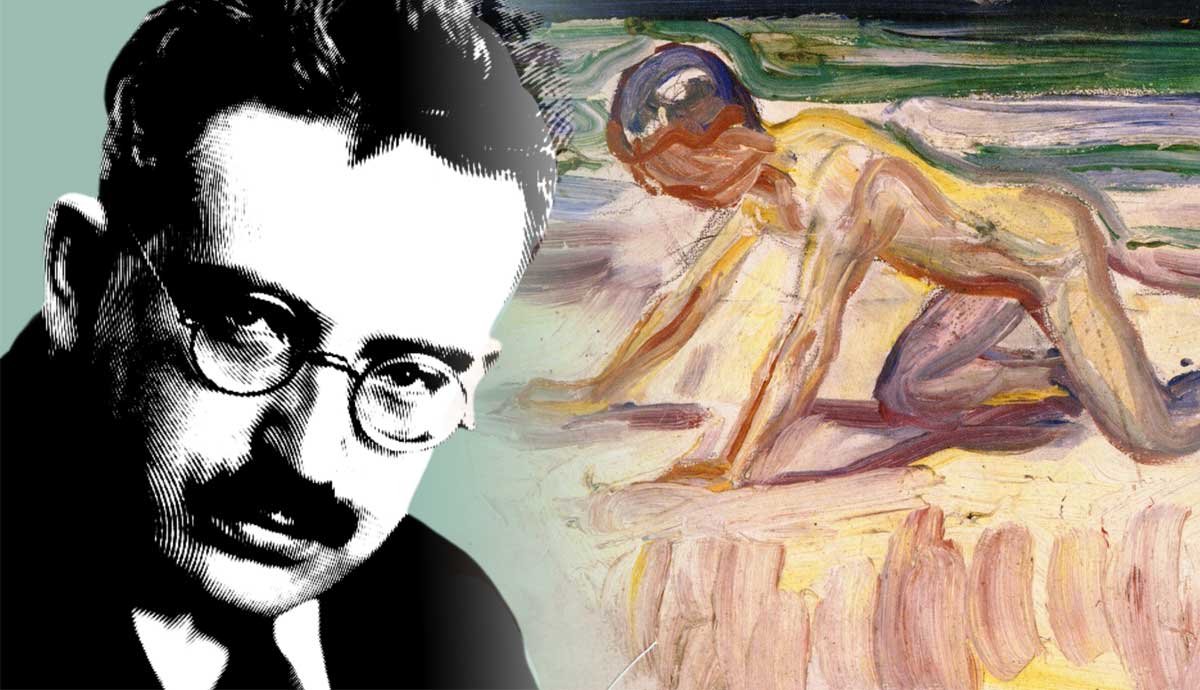

Benjamin provides a brief analysis of sexual fulfillment, pre-empting and then surpassing the Lacanian claim that we mislead ourselves into thinking that what we want is sexual fulfillment, when what we really want is to continue to suspend fulfillment and remain in desire. Benjamin agrees up to a point – to fulfill a desire is to detach ourselves from Mother Earth, attaining ‘rebirth’ of a wholly ambiguous sort.

Prophecy

What follows next amounts to Benjamin turning towards his conclusion. It is an astonishingly beautiful and lucid discussion of prophecy. Benjamin takes a stand against the fortune teller in favor of the kind of fortune which we are able to discern for ourselves by paying attention to events as they unfold. Prophecy lacks vitality.

“Omens, presentiments, signals pass day and night through our organism like wave impulses. To interpret them or to use them, that is the question. The two are irreconcilable.”

Putting the point another way, as he often does, “fate must bow to the body.” There is a sense in which this amounts to the claim that we make our own fate. Benjamin concludes this section by relaying the famous story of Scipio Africanus stumbling as he first touched Catharginian soil, and crying out: “teneo te, terra Africana.” There is a kind of political point to all of this as well, given Benjamin’s revolutionary outlook. The point of prophecy is to be sensitive to the correct moment, not just expressing predictions about the future. Naturally, this sensing is followed by an act of foretelling.

Walter Benjamin on Intuitive Understanding

Benjamin focuses on a way of living – that of the sailor – which is disorientated by travel, the flattening of the world by rapid transit. The sailor “lives on the open sea where, on the Marseilles Cannebiere, a Port Said bar stands diagonally opposite a Hamburg brothel […] The interlaced harbours are no longer even a homeland, but a cradle.”

Benjamin concludes by unlocking the key to the whole work. He previously wrote about the power of intuition, the form of knowledge which comes from paying close attention to what we know intuitively. “Nothing distinguishes the ancient from the modern man so much as the former’s absorption into a cosmic experience hardly known to later periods.” Benjamin presents the choice before human beings as between destruction, annihilation (of which the First World War was a foretaste), and procreation – going beyond foretelling, and moving towards a kind of creative action.

Benjamin argues that this action must be collective in nature: “The ancients’ intercourse with the cosmos was in the form of the ecstatic trance,” and this is the form of experience by which we gain knowledge of “what is nearest to us and what it furthest from us, and never one without the other.”