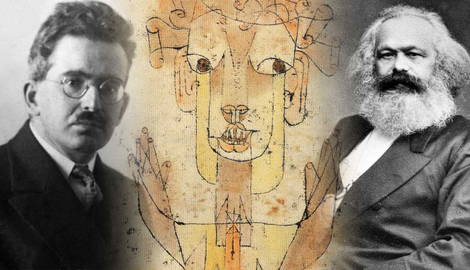

What is history, and how will it end? These are the stark preoccupations of Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History. This article explores Benjamin’s attitude to history by tracing the structure of the theses as Benjamin sets them out. Given the intentional ambiguity and extensive quality of Benjamin’s argument, there is really no other way to approach it.

This article begins with Benjamin’s opening parable of the chess-playing puppet, before moving on to his analysis of human nature and class struggle. Benjamin’s critique of social democracy is explored, and the article concludes where Benjamin himself does – with an analysis of apocalypse and annihilation.

The Method of Walter Benjamin: What is Historical Materialism?

Given that it is one of the central concepts of the Theses, it is worth starting with a basic definition of what historical materialism is. It is the name given to Karl Marx’s theory of history, and it holds that the ultimate cause and moving power of historical events are to be found in the economic development of society and the social and political upheavals wrought by changes to the mode of production. It is the central concept Benjamin is attempting to analyze.

Benjamin begins with a story, apparently one he had been told rather than one he invented. In it, there is a puppet that appears to play chess autonomously. The chessboard is set on a glass table, which is shown to be empty. However, it only appears to be empty. This appearance is achieved by a system of mirrors. Inside, there is a ‘hunchback,’ who happens to be an expert chess player. The point of the analogy is this:

”The puppet called ‘historical materialism’ is to win all the time. It can easily be a match for anyone if it enlists the service of theology, which today, as we know, is wizened and has to keep out of sight.”

Historical materialism is the puppet, and theology is the hunchback.

Happiness and Redemption

The next section focuses on a quote from Hermann Lotze:

“One of the most remarkable characteristics of human nature is, alongside so much selfishness in specific instances, the freedom from envy which our present displays to towards the future.”

Happiness, Benjamin suggests, is bound up in our own time, or rather in reiterations and possible versions of our own time – friends we could have made, lovers we could have had, and so on. Benjamin goes on to suggest that “our image of happiness is indissolubly bound up with the image of redemption.” This, Benjamin says, can also be applied to the past. Every generation has a redemptive power with respect to those previous. “The past has a claim…which cannot be settled quickly”.

Conversely, one thing which reinforces the decision not to distinguish between ‘major’ and ‘minor’ historical events – that is, to not develop any sense of what is historically important – is to recognize that the criterion of historical importance is in the future: “only a redeemed mankind receives the fullness of its past.”

Class Struggle

Benjamin then moves on to attempt a novel definition of a central Marxist concept, that of class struggle. Benjamin defines it as the fight for the “crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual thing could exist.” The forms that the latter take in this context are certain traits or dispositions: “courage, humour, cunning and fortitude.” This is because they have retroactive force: they qualify all victories and defeats.

“As flowers turn toward the sun, by dint a secret heliotropism the past turns towards the sun rising in the sky of history.” Benjamin concludes with a warning about the subtlety of this change: “a historical materialist must be aware of this most inconspicuous of transformations.” Benjamin then returns to our conception of the past. He posits that the past can only be understood as a momentary image. He then quotes the writer Gottfried Keller: “the truth will not run away from us”, and claims that this is the critical move of historical materialism – the recognition of every image of the past in the present, without which the past threatens to disappear entirely.

Benjamin on the Messiah

On a similar point, Benjamin then goes on to characterize historical articulation as not a matter of recreating things as they really were, but as seizing hold of memory at a moment of danger. “The Messiah comes not only as the Redeemeer, but as the subduer of the Antichrist.” This is the image of the past which historical materialism is concerned with.

One of the recurrent themes in Benjamin is this sense of mission, of time which is not homogenous, but at once recurring and converging: “Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.”

Benjamin then turns to another element of recreating the past – that of empathy. This is, he claims, central to historicism – the attempt, among other things, to recreate the past. Here he quotes Flaubert: “Few will be able to guess how sad one must be to resuscitate Carthage.” The problem with empathy for Benjamin is that we shall generally end up empathizing with the victors. Another problem with the historicist desire to recreate the past is that it involves a veneration of cultural treasures, whose real meaning resides not just in the genius of those who created them but in the horror and barbarism of the conditions required to create them, which we are unwilling to contemplate.

The State of Emergency

The historical materialist disassociates himself from this standard way of viewing the past: it is “his task to brush history against the grain.” Benjamin is writing the theses in 1940, in the early days of the Second World War. It is striking that he first mentions fascism in order to emphasize how the state of things which has brought it about is anything but abnormal, and the apparent ‘state of emergency’ is not a genuine one. His call is for a real state of emergency, something to break with the past. We learn this, so he says, from the “tradition of the oppressed.”

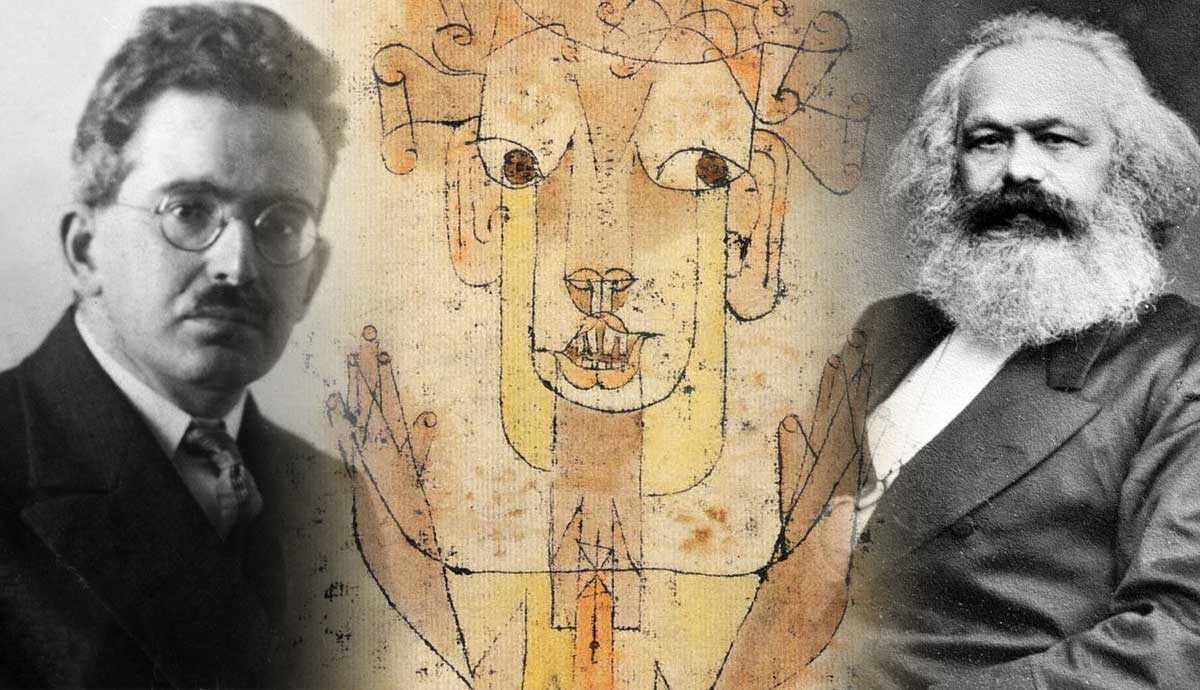

This leads Benjamin on to, perhaps, the most famous passage in this work: that in which he describes the Angelus Novus (a painting by Paul Klee), taking it to represent the terrible bond history is held in: contemplating the horror of the past but forced into the future. The past is left behind, even as the ‘debris’ piles higher and higher. The storm which carries it, so Benjamin says, is called progress.

Benjamin then shifts direction, and characterizes himself and his project as one of turning away from the world and its affairs, imposing a kind of monastic discipline, or at least situating it as an extension of the tradition which counts monasticism as a part.

This turn to an ascetic life is necessary given the uselessness of politicians who are meant to be fighting fascism, their “stubborn faith in progress,” confidence in their “mass basis,” and “integration into an uncontrollable apparatus,” which Benjamin takes to be “3 aspects of the same thing.”

The point of this monastic ideal is to “convey an idea of the high price our accustomed thinking will have to pay for a conception of history which avoids any complicity with the thinking to which these politicians adhere.” Conformism within social democracy is a large part of its failure: Benjamin states that nothing has corrupted the German working class as much as the inertia with which it was going with the flow of history.

Defining progress in the context of technological development goes hand in hand with the centralization of labor as the source of power and wealth. It is Marx, Benjamin says, who notices the power dynamics which lie behind this shift in German society: “the man who possesses no property other than his labor power … must of necessity become the slave of other men who have made themselves the owners”. This conception of labor is paired with a predatory, consumptive view of nature. Benjamin draws the contrast here with Fourier’s utopianism, which focuses on unleashing the hidden potentialities in nature.

The Categories of Social Democracy

Social democracy assigns to the working class the role of redeeming future generations, rather than turning it into the last enslaved class fated to redeem generations of the past. According to Benjamin, progress in the social democratic conception involves the defense of dogmatic claims. In particular, (1) progress is of mankind itself, not just their “ability and knowledge;” (2) progress has no limit, in accord with the “infinite perfectibility” of mankind; and (3) progress was regarded as irresistible.

Criticism of progress should go beyond a critique of these dogmas of progress, and focus on what unites them; “the concept of the historical progress of mankind cannot be sundered from the concept of its progression through a homogenous, empty time.” History is not homogenous, because time is filled by the presence of now: “to Robespierre ancient Rome was a past charged with the time of the now which he blasted out of the continuum of history.”

Walter Benjamin on Revolution and the End of History

Revolution, for Benjamin, means introducing a new calendar. Awareness that they are about to “…make the continuum of history explode is characteristic of the revolutionary classes at the moment of their action.” The historicist gives the “eternal image of the past,” the “once upon a time” – the historical materialist must be able to conceive of the present not as a transition, but as time that has stopped entirely. This is the position from which history is written.

The historical materialist “remains in control of his powers, man enough to blast open the continuum of history.” Historicism logically concludes with universal history, whereas materialist historiography aims towards a “constructive principle.” Thinking is not just a flow of thought, but the point at which thought ceases, and the structure of that thought can crystallize into a monad. Benjamin concludes with the observation that this is a revolutionary opportunity to recapitulate the battles of history.