Wangechi Mutu’s works show a fascinating combination of traditional art practices, African mythology, and elements of contemporary Western culture. Mutu is fascinated with the dualities of ugly and beautiful, artificial and natural, creative and destructive. In line with the philosophy of Afrofuturism, Mutu explores alienation and grotesque transformations of bodies and identities under the veil of technological and media advancements. Here are 8 defining facts about Wangechi Mutu’s art that you should definitely know.

1. Wangechi Mutu Was Born in Nairobi, Kenya

Wangechi Mutu was born in 1972 on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya. She obtained her first education in a Catholic convent school before moving to Europe, and then to the United States. Her training was diverse. Mutu studied fine arts, design, and anthropology, while also keeping a close connection to her culture and traditions, blending her personal experiences with her academic ones.

After a year of studying at the Parsons School of Design, she realized that she could not afford to pay the tuition fee anymore. Going back to Kenya was not an option, since the young artist saw this as a sign of defeat. That was the moment when Wangechi Mutu decided to apply to Cooper Union, a private, tuition-free college in New York. Cooper Union is known for its low acceptance rates and its famous alumni that includes Lee Krasner, Audrey Flack, and the legendary sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance Augusta Savage.

2. She Fuses African and Western Cultures

As an African artist, Wangechi Mutu is well aware of the destructive impact of colonialism on African culture and its worldwide reception. She often attempts to reimagine history by combining elements of African and European art and treating them as equally important. In 2019, The Metropolitan Museum commissioned a series of sculptures for their facade from Mutu. Given the building design, Mutu’s first thought was to create caryatides—figures of women holding the walls like columns.

However, she adapted the concept by sculpting figures of African women wearing garments inspired by the traditional dress of several African tribes. By doing so, she subverted the colonial narrative of art history, positioning African imagery and iconography in a place that is traditionally reserved for Western beauty standards. Her figures served as the guardians of knowledge and legacy of the whole of humanity, celebrating its previously omitted aspects. Commissioning such work from an African artist was a remarkable step for the Metropolitan Museum of Art since the institution frequently finds itself amid controversies surrounding looted art.

3. Mutu Promotes Afrofuturism

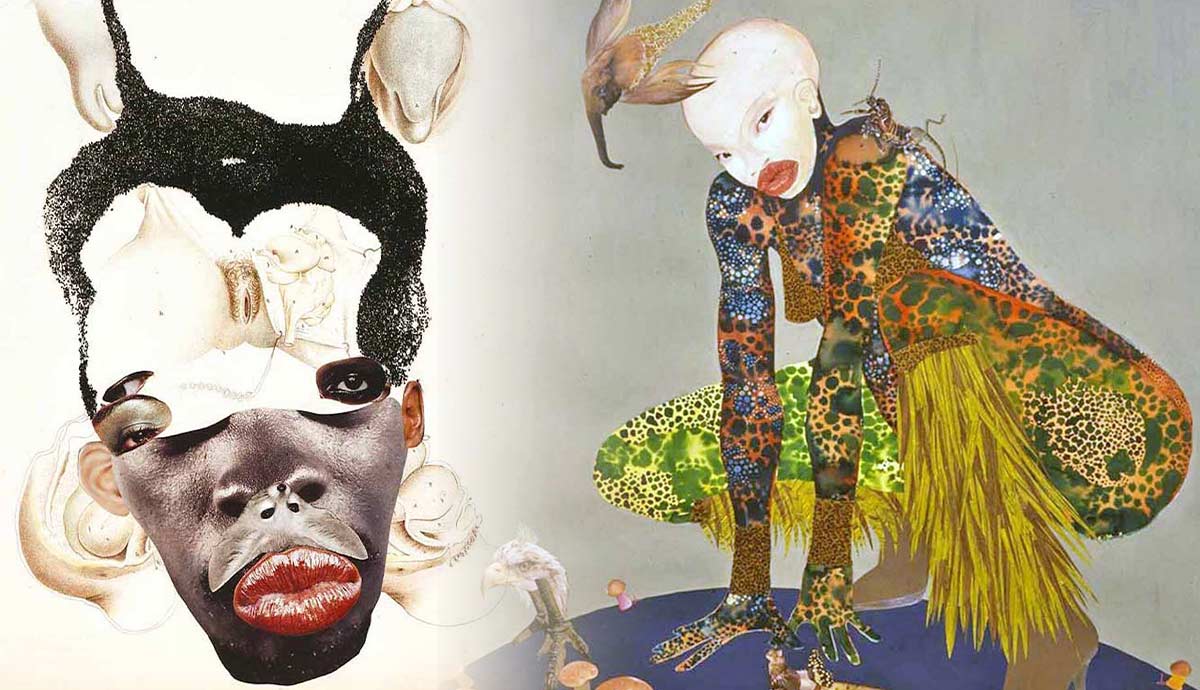

Wangechi Mutu is often listed as one of the artists representing the aesthetics and philosophy of Afrofuturism. The Westernization of Africa erased many traditional beliefs, symbols, and practices from everyday life. Afrofuturism imagines the future with African culture revived and functional, embedded into technology, architecture, and design. The concept grew from the genre of science fiction, with African writers and thinkers noticing the whiteness and Western-centeredness of the visions of possible futures. Racial exclusion and erasure had somehow crept into the realm of imaginary and eternal possibilities. Afrofuturism reappropriates contemporary culture and blends it with traditional African art, creating another type of futuristic utopia.

Mutu’s characters often appear as hybrids of humans and mechanisms, like the representatives of some alien race that developed much further than humans. The transhumanist concept of extending human possibilities by implementing technology also reflects in her silhouettes, which are both fascinating and repulsive, drawing attention and provoking the viewer to turn away simultaneously.

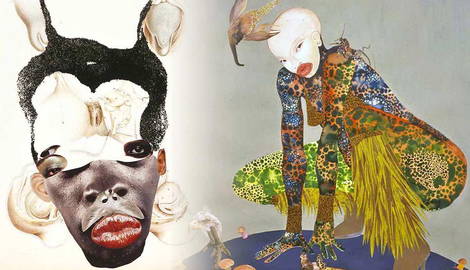

4. She Started Her Artistic Career By Making Collages

Today, Wangechi Mutu is known as a sculptor and performance artist, but her artistic career started with collages and assemblages. During her early career days, she could not afford to buy artistic material, so she often experimented with found objects by extracting and transforming their meanings.

Transformation is, in fact, Mutu’s important preoccupation. Specifically, she focuses on the transformation of the human body through disease, physical activity, and even fashion. The impermanence of the biological form is a central element of her work, with strange hybrids comprised of recognizable yet often unrelated parts constructing new beings.

Mutu moved to sculpture in her late twenties, believing that it was the only medium that would allow her to truly create and reflect upon the matters of body, culture, transformation, history, and the present. Today, in her studio in Nairobi, she works with natural materials sourced in her native region, blending futuristic silhouettes with traditional textures. The physical transition from magazine cutouts to clay and fiber mimics the conceptual tradition of Mutu’s art, moving from contemporary culture to tradition.

5. For Mutu, The Human Body is an Act of Rebellion

As an African woman and an anthropologist, Wangechi Mutu is well aware of how human bodies turn from biological subjects to political ones. In her interviews, she remembers looking through books about African tribes and cultures published by Western publishers. Although their perspective was rarely correct, Mutu felt like she was being compared to these depictions no matter how accurate they were. Moreover, she noticed how the culturally imposed beauty standards often become racialized categories, with Black bodies being compared to unattainable white ideals.

Mutu examined illustrations, fashion magazines, advertisements, and other sources of media in search of the ideal face and body. The ideal body was nowhere to be found, no matter how well you combined the so-called perfect features, attempting to fit them all onto one face. Some standards turn out to be mutually exclusive—beauty transforms into ugliness, sensuality into grotesque vulgarity, and harmless play into deadly violence.

6. She Draws Inspiration From Legendary Black Artists And Performers

One of the most inspirations for Wangechi Mutu’s art is the American performer Josephine Baker. Although Baker is a popular inspiration among artists, Mutu is specifically interested in the way the legendary dancer appropriated racist stereotypes. Baker’s public image and costumes had nothing to do with the actual African culture, yet it was exactly what the European public expected to see. Baker, who was born in the USA, adopted a costume of an ‘African woman’ for her audience in Paris.

Another important historical character studied by Wangechi Mutu is Saartjie Baartman, a Xhosa woman exhibited in Europe in the so-called freak shows. Known among the public as Hottentot Venus, Baartman was famous for her unusual body type, common among the women of her area. For years, Saartjie Baartman suffered abuse and dehumanization and ended her days in poverty. Her story is both a deep personal tragedy and an illustration of how a living being could be destroyed by ideas of acceptable beauty standards. The advertisements for Baartman’s tour described her as the missing link between an animal and a human. Calling her a Venus was another way to juxtapose an enslaved Black woman, forcefully moved from her home, with the intangible ideal of the Roman goddess.

7. African Mythology Serves As Mutu’s Important Inspiration

The extinction of traditional African beliefs and myths concerns Mutu. Her mother was raised in the Christian faith but she barely shared her memories of tradition with her children. The revival of African mythology is an act of reevaluation and a step further toward healing the collective colonial trauma. Femininity is particularly important in this concept due to its connection with fertility and the social function of women in traditional communities. Rituals and beliefs surrounding various stages and aspects of women’s lives comprise a large body of cultural knowledge that is now being revived by artists like Mutu.

Mutu’s works often feature creatures from Kenyan folklore and tales. In her video work Nguva, she tells the story of a sea creature, a Kenyan analog of a siren. Nguva appears in the form of a beautiful woman but she is far from human. This entity uses human weaknesses to lure them into ocean waters. Some Kenyans still believe that these creatures really exist. Mutu suggests that mythological creatures like nguva could represent some other level of consciousness unavailable to humankind.

8. Wangechi Mutu Uses Anatomical Drawings For Making Collages

In her collages, Wangechi Mutu uses photos from magazines, advertisements, and anatomical illustrations from centuries-old medical atlases. Mutu inherited her interest in medicine from her mother who worked as a nurse. Looking through books on tropical diseases, Mutu noticed a combination of fascination and disgust. Unlike many other internal illnesses, tropical diseases show signs on the body, gradually expanding and consuming it.