In the Arthurian legends, Lancelot is one of the most famous and popular characters. He was one of Arthur’s best and most powerful knights. However, despite his initial loyalty, he eventually turned on Arthur, engaging in an affair with the king’s wife, Guinevere. This dramatic story is a key feature of the Arthurian legends today. However, Lancelot is commonly understood by scholars as an invention of French writers. In other words, he did not exist in the earliest versions of the legends. But not all scholars agree. Might his origins be within the Welsh tradition?

Lancelot’s Apparent Origin

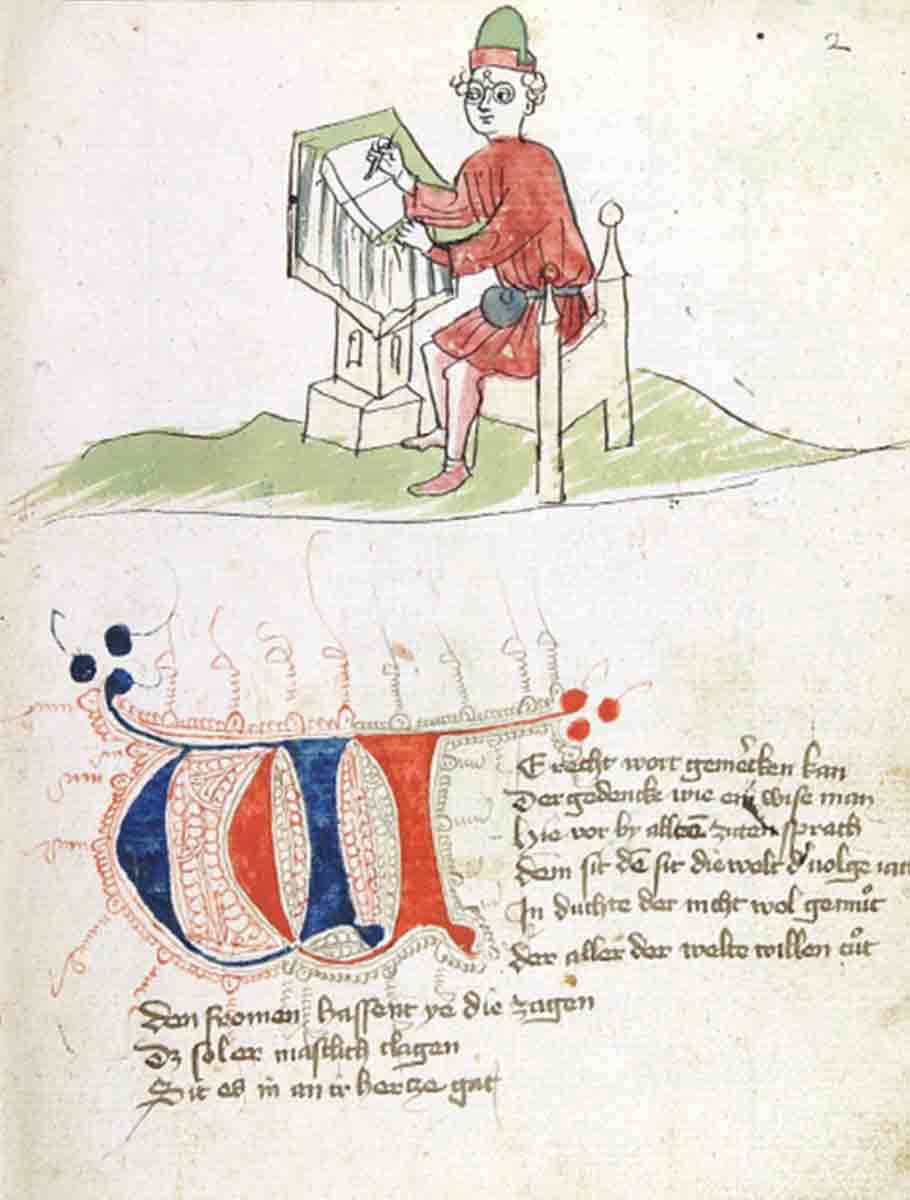

The earliest known appearance of Lancelot by that name is in the writing of Chretien de Troyes. He was a French writer who lived in the 12th century. He wrote shortly after Geoffrey of Monmouth produced his hugely influential Historia Regum Britanniae in c. 1137. Chretien’s version contains many notable differences from Geoffrey’s account.

One of these differences is the presence of Lancelot. In fact, Lancelot gets an entire story devoted to him, known as Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart. Since Lancelot does not explicitly appear with this name until the writings of Chretien, this has led to the logical conclusion that he is Chretien’s own invention. Since “Lancelot” clearly looks like a French name, and Chretien himself was one of the earliest French writers of the Arthurian legends, this seems all the more certain.

Nevertheless, many scholars over the years have proposed pre-Chretien origins for Lancelot. There is an enormous variety of theories, some more convincing than others.

Lancelot’s Overtly French Name

Many scholars have attempted to provide a non-French origin for this character’s name. Such scholars include Ferdinand Lot, Roger Sherman Loomis, Thomas Gwynn Jones, Norma Loore Goodrich, and others. Based on this line of investigation, they have limited themselves to attributing the origin of Lancelot to pre-Chretien figures whose names could plausibly have become “Lancelot.”

However, there is an important fact which has a large bearing on this issue. Historian Flint Johnson highlights that several manuscripts of Chretien’s work actually have the form “L’Ancelot.” The word “ancelot” is French for “servant.” Hence, “L’Ancelot” would mean “the Servant.” In other words, it is entirely possible that the name that Chretien gave to this character was actually a title. This would mean that the original character on which he was based (if not just Chretien’s invention) could have had a completely different name. Crucially, this means that there is no inherent reason to only look at figures whose names could have evolved into “Lancelot.”

Maelgwn Gwynedd

When we look at the various potential origins for Lancelot that have been proposed by scholars with this key fact in mind, one candidate stands out as a particularly strong possibility. This candidate is Maelgwn Gwynedd. What is particularly interesting about Maelgwn is that he is not only a pre-Chretien figure but that he is also known to have been a historical king. He was one of the five kings mentioned by the 6th-century writer Gildas in De Excidio.

This theory involves ignoring the name, since, as we have seen, “Lancelot” likely just means “the Servant” in French. When we just look at the information about Maelgwn as a king, a convincing case can be made that he was the historical prototype for Lancelot. When this theory was first proposed in the 19th century, there were some obvious flaws in the logic and evidence used, and thus it was discarded. However, with the benefit of more modern scholarship, particularly regarding the name of Lancelot’s kingdom, it is worth another look.

Maelgwn as a Powerful Ally of King Arthur

When examining whether Lancelot could reasonably have been derived from the figure of Maelgwn Gwynedd, we do well to look at their overall profiles. Lancelot, as we have already seen, was famously one of Arthur’s best and most powerful knights. Does this basic concept match what the pre-Chretien sources wrote about Maelgwn Gwynedd? Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote about Maelgwn:

“After him succeeded Malgo (Maelgwn), one of the handsomest of men in Britain, a great scourge of tyrants, and a man of great strength, extraordinary munificence, and matchless valor.”

There is no doubt that this basic description of Maelgwn is a good match for Lancelot. This fundamental match is something which perhaps no other proposed candidate for the historical Lancelot achieves. Maelgwn was allegedly handsome, brave, and powerful, and all this to a remarkable degree.

While Geoffrey does go on to mention Maelgwn engaging in homosexual conduct, which does not feature in the tales of Lancelot, this is not present in any other record of Maelgwn either.

What about the concept of Lancelot being an ally of Arthur? Geoffrey of Monmouth does not specifically mention this point regarding Maelgwn. Nevertheless, we can find this elsewhere in early tradition. We find it in the Welsh Triads, which are a collection of medieval traditions grouped into sets of threes. Triad One is called the Three Tribal Thrones of the Island of Britain. It lists King Arthur’s three most notable royal courts. The first entry reads as follows:

“Arthur as Chief of Princes in Mynyw, and Dewi as Chief of Bishops, and Maelgwn Gwynedd as Chief of Elders.”

According to this relatively early trace of Welsh tradition, Maelgwn was held to be the Chief Elder at one of King Arthur’s most important royal courts. Although the tradition of Maelgwn as one of Arthur’s allies does not have a prominent part in later records, this demonstrates that it was originally there. In fact, he was held to have been one of Arthur’s most important and privileged allies.

Lancelot’s Kingdom

So far, we have seen that Maelgwn matches the basic profile of Lancelot, as a handsome, brave, powerful ally of Arthur. However, while an excellent match, this is also rather generic. To connect the two figures on a more specific level, let us now examine Lancelot’s kingdom. The name of this kingdom is variously seen as Benwick, Benoic, Genewis, and other variants. The form “Genewis” is used by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven in his German Lanzelet. This appears to be a variant of “Gomeret,” the name of the kingdom of Ban (Lancelot’s father) according to Chretien.

Many scholars have argued that the name of Lancelot’s kingdom is a reference to Vannes in Brittany. This certainly seems to be the case for Gannes, the kingdom ruled by the brother of Lancelot’s father. Scholars have argued that Lancelot’s father’s own kingdom is just a duplicate of this. In other words, both his father and his uncle ruled the same kingdom. The forms “Genewis,”

“Gomeret,” and even “Benwick” have all been argued to be alterations of “Guenet,” the Breton name for Vannes.

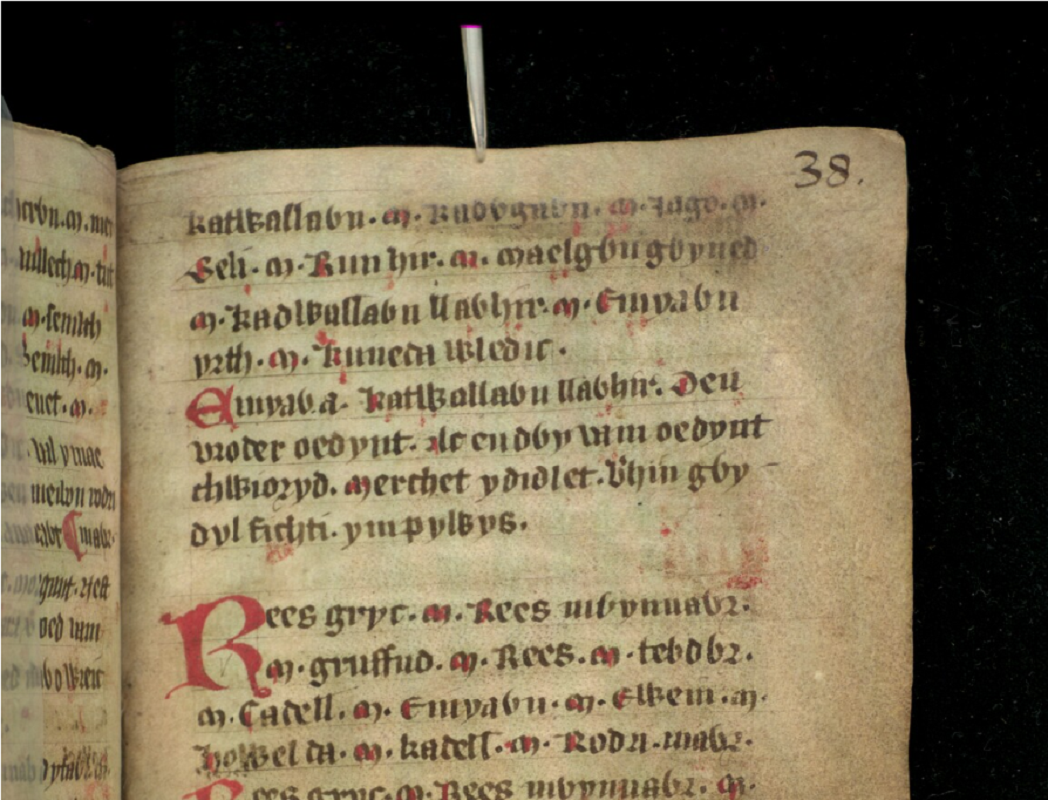

The reason that this is so significant is that the Breton name for Vannes, “Guenet,” is virtually identical to the name of Maelgwn’s kingdom. The modern spelling is “Gwynedd,” although it is often seen as “Gwyned” in medieval manuscripts, such as the Jesus College MS 20. Therefore, it would have been extremely easy for a French writer to have mistaken Gwynedd for Guenet, or Vannes. This is especially so given that a French writer would obviously have been more familiar with the Breton location, since it is within France.

Some scholars have even identified Lancelot’s kingdom directly as Gwynedd, as noted by historian Christopher W Bruce. Prominent Arthurian scholar Elspeth Kennedy mentioned both identifications in a footnote, without commenting on which one she felt was more likely.

Whether the name came from Guenet or directly from Gwynedd, the connection to Maelgwn is easy to make. This provides very strong support to the conclusion that Maelgwn was the historical origin behind the figure of Lancelot.

Other Evidence That Maelgwn Was the Historical Prototype of Lancelot

The fact that Maelgwn was a powerful and important ally of Arthur, whose kingdom corresponds to the name of Lancelot’s kingdom, is not the end of the story. There are various other details about Maelgwn that match the character of Lancelot. For example, Maelgwn ruled in the generation immediately following Arthur’s supposed reign. Recall that Geoffrey of Monmouth presents him as a “scourge of tyrants.” Similarly, Lancelot is presented in the legends as putting down the rebellions of Mordred’s two sons in the years following Arthur’s death. We see this as early as the Vulgate Mort Artu, written just 50 years or so after Lancelot’s first appearance.

Interestingly, this same source notes that Lancelot ended up dying of illness. This is notable in view of the persistent tradition that Maelgwn Gwynedd died of plague, first seen in the 10th-century chronicle Annales Cambriae.

Before his death, Lancelot is described as abandoning society and becoming a monk. Interestingly, Gildas mentions the fact that Maelgwn at one point gave up his throne to pursue a religious life.

Did the Character of Lancelot Come From Maelgwn?

Even more details could be mentioned. To provide just one more example, Lancelot’s son Galahad was famous for his virtue and his position as a “perfect knight.” Similarly, Maelgwn’s son Rhun is remembered in the Welsh Triads as one of the Three Fair Princes of the Island of Britain. Both Galahad and Rhun were also remembered for being illegitimate.

What can we conclude from this evidence? Of course, we cannot be dogmatic about the origin of Lancelot. Perhaps he really was just an invention of Chrétien de Troyes. However, what this analysis has shown is that a good case can be made that the character of Lancelot actually originated with Maelgwn Gwynedd, a historical figure. This powerful king was remembered as a brave and handsome ally of King Arthur. The name of his kingdom is likely the origin of the name of Lancelot’s kingdom. He had a leading position in the period immediately after Arthur’s reign. At some point after abandoning the throne to pursue a religious life, he is reported to have died of illness, just like Lancelot. Maelgwn Gwynedd can surely be considered a leading candidate for the prototypical Lancelot.