War was the defining characteristic of Roman culture. The famous gates of Janus — closed only in times of peace — were shut less than a handful of times during the many centuries of Rome’s ascendancy. A state almost perpetually at war.

“Throughout history, the principal power is technological superiority in armaments, …”

[Niall Ferguson in “All is Not Quiet On The Eastern Front” ]

Ancient Rome was no exception, the once obscure Latin city enforced her dominion, through war, over most of the known ancient world. Rome’s talent and pragmatism in deploying the weapons of the Roman legionary were critical to her success.

The Weapons of the Roman Legionary: A Long and Complex Story

Evolving over a long history of conflict, Roman weaponry was devised, designed, and improved many times over to meet the complex challenges of a city that would become an empire. Roman weaponry spanned nearly 1100 years of evolution. In that context, there was no single Roman army. Rather, over time, there were many Roman armies, just as there were many Romes.

The irregular citizen militias of Rome’s early Republic were very different to the later legions of the Republic and Imperial ages. Organizational evolutions, from phalanxes to maniples and cohorts, brought significant changes in how Rome fought and how its weapons developed. Increasing professionalization — most marked during milestones like the Marian reforms of the late 2nd century BCE — corresponded with deep changes to Roman arms.

The dawn of the imperial period saw even further professionalization and formalization. The widescale adoption of auxilia as significant components of Rome’s military machine in turn influenced the Roman army, its equipment, and war fighting capabilities.

Later military reforms like those of Diocletian in the early 4th century CE also brought massive changes in military distribution, organization, and manpower. As the later empire evolved, recruitment of non-Roman people from the fringes of the empire, and even beyond saw a degree of “barbarization” in the roman army that greatly influenced its weaponry.

This was not just seen in auxiliary roles but increasingly among core “Roman” armies that were dominated by manpower from communal alliances and treaty obligations. Such was the level of transformation (largely Germanization) in men, weapons, and organization, that an early or Republican legion might not have recognized a late “Roman” army at all.

Across these huge evolutions, significant changes in Roman arms occurred although we don’t have all the details. There are many gaps in our sources, with even archaeology struggling to shed light on many questions. Several periods of Roman history remain dimly lit.

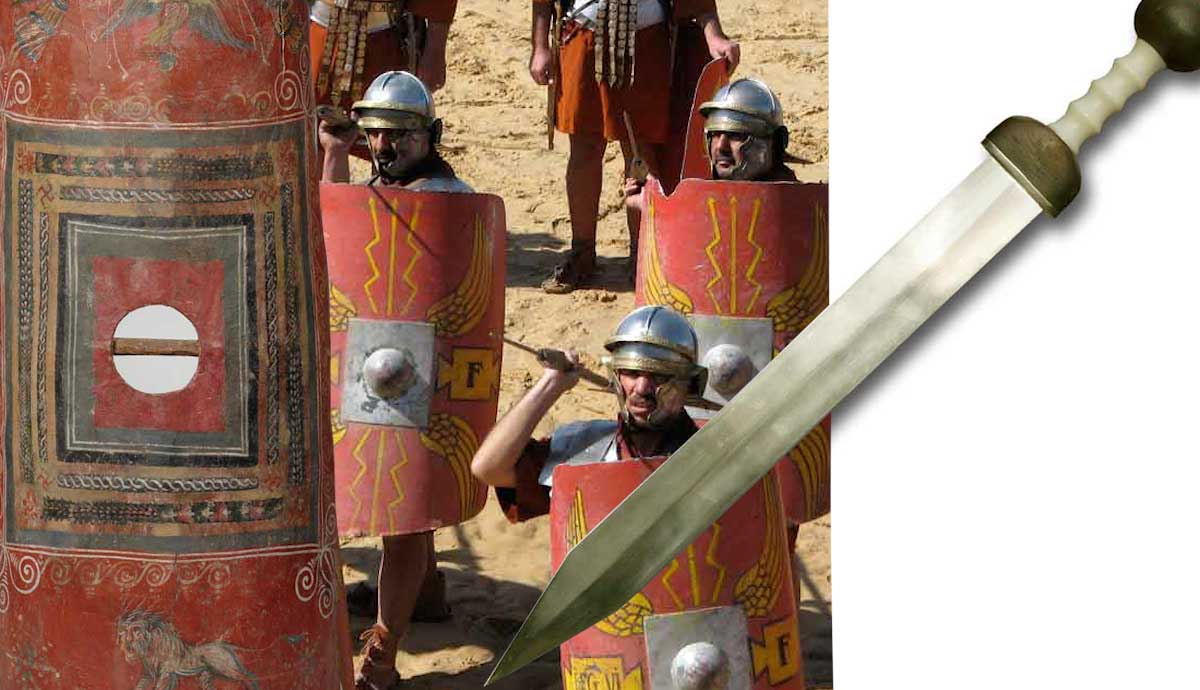

The Gladius Hispaniensis: Spanish Short Sword

If you had to pick one weapon of the Roman legionary, it would probably be the gladius Hispaniensis. The ubiquitous Roman short sword was an essential side arm of legionaries, generals, and emperors. Though swords existed both before and after its adoption, it was the gladius Hispaniensis that came to symbolize Roman warfare. The most surprising thing about this weapon — as indicated by its designate “Hispaniensis” — was that it originated from Spain. It was adopted from Rome’s Celtiberian tribal enemies in Iberia (modern day Spain).

Facing highly effective Iberian warriors in the armies of their enemy Carthage, the Romans soon realized that the short, double-edged and pointed sword possessed many advantages. At close quarters it was an effective stabbing weapon, as well as having a slashing capability. In the tight melee of battle this was a breakthrough where longer swords, that relied on long slashing strokes were often nullified by the constricts of battle.

The ease with which the Romans adopted a “barbarian” technology from a Celtic people that they deemed “culturally inferior” is notable. But not at all at odds with that most defining Roman trait of pragmatism. The historian Polybius gives us the low-down:

“The Celtiberians excel the rest of the world in the construction of their swords; for their point is strong and serviceable, and they can deliver a cut with both edges. Wherefore the Romans abandoned their ancestral swords after the Hannibalian war and adopted those of the Iberians.”

[Polybius Histories, Fragment XXII (96)]

The short-sword gladius would not be the only war technology that Rome would “borrow” from the tribal Celts some of whom were master metalsmiths (Examine also the adoption of lorica hamata, or chain mail).

The gladius was much shorter than the longer swords that Rome often faced, used by their many enemies. With a blade length of c. 60 – 80 cm or 24 – 27 inches the gladius Hispaniensis was a relatively short infantry weapon, with a minimal hand guard and equally modest pommel.

Writing in the late 4th century CE, the commentator Vegetius noted the cold scientific equation:

“[legionaries] were taught not to cut but to thrust with their swords. For the Romans not only made a jest of those who fought with the edge of their weapon, but always found them an easy conquest. A stroke with the edges, though made with ever so much force, seldom kills, as the vital parts of the body are defended by the bones and the armor. On the contrary, a stab though it penetrates but two inches is generally fatal.”

[Vegetius, De Re Militari, Book 1]

Lethality was key. Roman legions stabbed and hacked their way to imperial expansion, constituting the most efficient killing machine the ancient world would ever witness. A famous story in the third century BCE tells how shocked Phillip V of Macedon’s army were when they encountered the principal weapon of the Roman legionary:

“…, when they had seen bodies chopped to pieces by the Spanish sword, arms torn away, shoulders and all, or heads separated from bodies, with the necks completely severed, or vitals laid open, and the other fearful wounds, realized in a general panic with what weapons and what men they had to fight.”

[Livy, History 31.44.4]

The gladius unnerved men who were used to war. Various famous types of gladii have been found by archaeology, including the ‘Mainz type’ and ‘Pompei type’. Each type tended to get slightly shorter in length as it evolved through the imperial period.

In the later Empire, its use seems to have ended with a longer, heavier sword, the spatha, increasingly adopted by Rome’s infantry. Yet the Gladius Hispaniensis defined Rome. A weapon that won an empire, it remains to this day a potent symbol of Roman military power.

The Scutum (Shield)

The famous infantry shield was an essential component of the Roman army. While we might think of a shield as a “defensive” armament and, therefore, not a weapon, this would not be true of the Roman scutum. It could be used as a tool of aggression, and it afforded legionaries the ability to hold their enemies at bay at close quarters. Crucially it provided the essential conditions with which to exploit the lethal gladius. Without this component, the gladius was denied its optimal value.

Typically, 4 feet long by 2.5 feet wide and originally oblong in shape, the scutum would evolve by the 1st century BCE to be rectangular. It was made with wood or layered wooden strips. Early Republican examples were described by Polybius:

“It consists of two layers of wood fastened together with bull’s-hide glue; the outer surface of which is first covered with canvas, then with calf’s skin, on the upper and lower edges it is bound with iron to resist the downward strokes of the sword, and the wear of resting upon the ground. Upon it also is fixed an iron boss (umbo), to resist the more formidable blows of stones and pikes, and of heavy missiles generally.”

[Polybius, History 6.23]

This was not Rome’s earliest (or sole) shield type, but it was the most long-lasting and impactful. It became a widespread classic of the legions. Some ancients believed that Rome had taken it from the fearsome Samnites, though dates here are problematic. Others attribute it to the early general Camillus (who predated the Samnite wars) who added iron edging to the scutum, giving it greater durability and strength. What most scholars suppose is that the Romans copied the scutum from one or more of their Italianate neighbors.

The scutum had a central iron boss which gave further strength and protection to the wearer. Crucially shields evolved to be cylindrical in shape, curving around the holder, protecting both the front and sides. See the scutum found at Dura-Europos in Syria

The curvature of Roman shields afforded natural deflection to oncoming blows and missiles. Shields were covered in leather and often bore motifs and designs. Held in the left hand the scutum could be slung on the back during marches and supported by straps. In battle, it provided protection from shin to chin, while in battle it offered overlapping cover to the man on the left. This was crucial for close-quarter fighting, where tight bodies of infantry became collectively more resilient from the protection offered to the man next to them. Look to the shield tactics of modern-day urban riot police to gain an appreciation of how this provided both personal and collective protection.

Used to smash, barge, and slam opposing forces, in the hands of trained soldiers, the scutum was also a weapon. At the battle of Mevania in 308 BCE, Livy describes how the Roman force rolled over their Umbrian opponents:

[The Romans] … raced forward against the enemy. They did not attack them as though they were armed men; … the action was everywhere fought with shields rather than with swords, men were knocked down by the bosses of shields and blows under the armpits. More were captured than killed, …

[Livy, History, 9.41.17]

The scutum was also an offensive asset to individuals. Suetonius tells us an anecdote about one of Caesar’s veterans:

[Caius Acilius] … who in in the sea-fight at Massalia grasped the stern of one of the enemy’s ships, and when his right hand was lopped off, … boarded the ship and drove the enemy before him with the boss of his shield.”

[Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, 68]

The scutum had many uses in battles and sieges, the most famous being the testudo (tortoise) formation of interlocking shields, that allowed whole units to attack fortifications. Though it would gradually be abandoned from the 3rd century CE onwards, the scutum earned its place in history.

The Pilum / Javelin

The final crucial weapon of the Roman legionary was the pilum; a Roman javelin type that made a huge impact on the battlefield. The pilum was a piece of war technology perfected over centuries.

The pilum was a distinct throwing weapon, not to be confused with a spear “hasta” which the early Romans also used. Eventually carried by all legionaries, it gave soldiers the ability to perform as missile troops. This amalgamation of functions was relatively rare in ancient armies where most missile troops tended to be ancillary specialists and did not also act as line or heavy infantry.

In the early Republic, the role of missile troops had originally fallen to a class of soldier known as velites. However, after the Marian reforms of late 2nd century BCE, these classes, and other types (Hastati, Principes, and Triarii) were subsumed into the common legionary function. In arming their legionaries with pila, the Romans amalgamated a mixed capability to great effect.

The classical pilum was made of cornel wood measuring c. 4.5 feet, it was attached to a thin iron shaft that carried a slightly larger barbed head. The iron component was also of c. 4 feet but was embedded into the wood and carefully fastened. This gave an overall weapon length of around just over 6 feet. The weighting and dynamics of the weapon were such that the narrow pyramidal head was designed to punch through shield, armor, flesh, and bone.

A well-thrown pilum was deadly and was used by Roman formations — often thrown en masse — to devastate enemy formations at mid to short range. They were often released just before the lines met. Even where it did not kill, it provided a deliberately designed dividend in that it would often skewer enemy shields, armor, and clothing, rendering opponents helpless with its barb and unwieldy shaft.

Polybius tells us that Republican troops carried two pila per man of varying weights. Even from this early period he makes clear that the design of the pilum was carefully configured, the product of true military science:

“They take extraordinary pains to attach the head to the haft firmly; they make the fastening of the one to the other so secure for use by binding it halfway up the wood, and riveting it with a series of clasps, that the iron breaks sooner than this fastening comes loose, … .”

[Polybius, History 6.25]

By the end of the second century BCE, this had evolved from a clasp fastening to iron nails. Plutarch attributes an ingenious design advancement to the great military reformer and commander Marius:

“… Marius introduced an innovation in the structure of the javelin. Up to this time, it seems, that part of the shaft which was let into the iron head was fastened there by two iron nails; but now, leaving one of these as it was, Marius removed the other, and put in its place a wooden pin that could easily be broken. His design was that the javelin, after striking the enemy’s shield, should not stand straight out, but that the wooden peg should break, thus allowing the shaft to bend in the iron head and trail along the ground, being held fast by the twist at the point of the weapon.”

[Plutarch Life of Marius, 25]

This design improvement allowed the iron shaft and wooden body of the missile to snap on impact, misaligning and impeding enemy movement. This augmented the hindering effect of the weapon and ensured that discharged pila could not be thrown back at their Roman owners, though they could easily be repaired after the battle. Some later pilum types carried metal weights designed to better punch through armor.

Writing in 58 BCE, Julius Caesar and his troops were still benefiting from the design of the pilum when they met mass ranks of the migrating Helvetti:

“The legionaries, … easily broke the mass-formation of the enemy by a volley of javelins, … . The Gauls were greatly encumbered for the fight because several of their shields would be pierced and fastened together by a single javelin-cast; and as the iron became bent, they could not pluck it forth, nor fight handily with the left arm encumbered. Therefore many of them preferred, after continued shaking of the arm, to cast off the shield and so to fight bare-bodied.”[Caesar, Gallic Wars, 1.25]

Rome would continue to use their deadly throwing weapon for several centuries to come. In later centuries the pilum seems to have passed out of use — so says Vegetius — and was replaced by another form of throwing spear, the spiculum, as well as by smaller hand-thrown darts called plumbatae. Yet, despite its passing, the pilum earned its place in history as a critically important weapon.

Weapons of the Roman Legionary in Conclusion

In evaluating just three “simple” weapons of the Roman legionary we can see Rome’s strength. The gladius, the scutum, and the pilum were designed solely for their intended purpose, to close with and efficiently destroy the enemies of Rome. In their use, development, and design we can see both simplicity and deceptive ingenuity.

In the gladius Hispaniensis and the scutum, Roman pragmatism did not blush at stealing the ideas of their adversaries. This happened many times over in the Roman story, their ability to absorb other cultures’ ideas being truly one of their greatest powers.

The Roman talent for developing and producing high quality arms on a mass scale was also conspicuous. In her history, Rome evolved her approach, constantly adapting weapons and practices on nothing less than the basis of a military science. At the height of her powers, every aspect of Roman warfare was conducted with a level of technical professionalism that eludes many modern societies even to this day.

With a deadly vision of purpose, the weapons we have examined were designed to operate as combined arms. Each rendered most effective when used in conjunction with the other. This gave the Roman legionary the tactical versatility needed to successfully fight a diverse multitude of opposing cultures across multiple terrains.

Deadly at range with the pilum, resolute (and dangerous) in defense with the scutum, and lethal at close range with the gladius. A powerful combination. Roman soldiers were not just the bearers of weapons, but something more akin to human weapons systems. Such was the power of Roman arms.