The transatlantic slave trade was one of the most disgusting, unforgivable periods of human history. For centuries, the great colonial powers of Europe profited greatly from the practice. However, by the late 18th century, a growing movement of brave abolitionists in Britain fought for the freedom of enslaved peoples. After banning the transportation of slaves in 1807, Britain established the West Africa Squadron, a naval force that patrolled the waves of the Atlantic in search of slave ships.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade

Beginning in the 16th century, the European colonial powers enslaved the people of Africa and subjected them to a life of cruelty and horror. Over the next 300 years, over 15 million people would become victims of the slave trade.

The British Empire first began participating in the slave trade in 1562. By 1730, Britain was the world’s largest slave-trading nation. Cities such as London, Liverpool, and Bristol became centers of the trade, with hundreds of ships leaving these cities bound for Africa. The ships would leave British cities filled with goods and cargo. Upon arriving on the African coast, these goods were exchanged for enslaved Africans.

The slaves would then be transported across the Atlantic Ocean in disgustingly inhumane conditions to colonies in the Americas. British ships would then return home, laden with slave-produced commodities like sugar, tobacco, and cotton. Between 1650 and 1807, it is estimated that three million Africans were transported on British ships.

The transatlantic slave trade brought extraordinary economic prosperity to Britain. The practice was strongly supported by many members of the British Parliament, many of whom had business interests in plantations, slave trading, and slave-produced commodities.

The Abolition Movement in Britain

Abolition was a contentious topic within British politics for some time. However, the country was heavily engaged in the practice and reliant on the cultivation of slave-produced commodities.

By the late 18th century, concerns about the humanity and morality of the slave trade were steadily growing in Britain. Quakers in Britain became the first groups to condemn the slave trade. They organized the first abolition political groups in Britain and, in 1783, delivered the first anti-slavery petition to parliament.

A significant abolitionist movement had emerged in Britain by 1783. Prominent figures included Olauduh Equiano, a formerly enslaved person who was kidnapped and enslaved as a child and transported to the Bahamas. Equiano would gain his freedom and published an autobiography detailing his experience of enslavement. His book became a best-seller and was distributed in numerous countries. It raised significant awareness of the brutality of slavery.

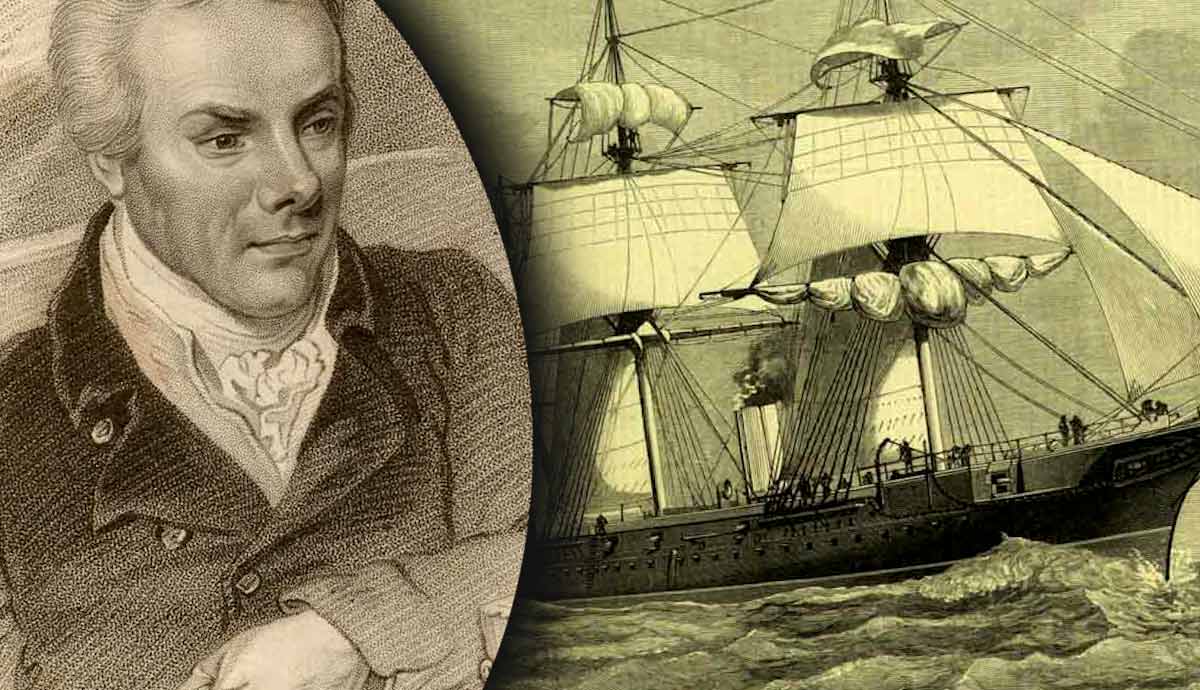

William Wilberforce was another vocal supporter of the abolitionist movement. As a member of parliament, Wilberforce made numerous speeches within the House of Commons calling for the end of the slave trade. He also founded the anti-slavery society alongside other activists like Hannah More and Granville Sharp.

After years of campaigning, the Slave Trade Act was officially signed in 1807. The act prohibited the purchasing of enslaved people. However, it did not abolish the practice of slavery altogether. Those already enslaved by 1807 were not given their freedom in British colonial territories. The practice of slavery was eventually banned throughout the Empire when the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1834.

Establishment of the West Africa Squadron

Although Britain had now introduced legislation that criminalized slavery, enforcing such a law was another matter.

A year after the Slave Trade Act of 1807 was introduced, Britain established the West African Squadron. Composed of British Royal Navy ships, the squadron was tasked with patrolling the West African coastline to intercept slave trading ships.

The first few years of the squadron’s operations, however, produced minimal results. At the time, the squadron only consisted of two ships, both of which were old, dilapidated, and extremely slow in comparison to most slave ships. Furthermore, the squadron was tasked with patrolling almost 3,000 miles of African coastline, an impossible task for a mere two ships.

The lack of support and resources provided to the squadron by Britain was mostly due to the ongoing Napoleonic Wars. Britain’s necessity to maintain naval supremacy over the French and Spanish navies during the conflict resulted in the squadron being disregarded by senior figures in Britain.

Another challenge facing the squadron was the diplomatic debacle of attempting to police ships belonging to allied nations. Although Britain had taken an important first step in tackling slavery, other European colonial powers and their economies were still closely intertwined with the slave trade. As a result, they were incredibly reluctant to cooperate with Britain. However, Britain was able to achieve some diplomatic agreements. Portugal, Britain’s long-time ally and one of the largest slave trading nations, signed a convention in 1810 that allowed British ships to police Portuguese ships carrying slaves. However, the convention still allowed Portugal to trade slaves between their own colonies.

Growing Support and Life Aboard the Squadron

Following Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Britain was able to allocate more resources to the West African Squadron. In 1818, Commodore Sir George Ralph Collier was dispatched to the Gulf of Guinea with six ships under his command, making him the first Commodore of the squadron.

The following year, the Royal Navy created a naval station in Freetown, Sierra Leone, which became the center of the squadron’s operations. This accompanied the already established Vice-Admiralty Court, which had been established in Freetown during 1807 to trial arrested slavers.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars also allowed greater discussion and cooperation between European states about slavery. Following Napoleon’s downfall, the European powers held the Congress of Vienna in 1814, which consisted of numerous diplomatic meetings to discuss the political landscape of Europe. As part of the final agreement, signed in 1815, Europe officially condemned the slave trade.

Life aboard the West African Squadron was harsh. Deadly diseases such as Malaria and Yellow Fever were rampant. The squadron also faced violent resistance from the slavers they encountered. The crew aboard the squadron’s ships faced significantly higher mortality rates than the entire Royal Navy.

However, the squadron still faced a number of legal obstacles that limited their operations and, importantly, resulted in the catastrophic loss of innocent lives. Until 1835, the squadron only had the legal right to board and seize vessels that had slaves onboard. As a result, there are numerous reported instances of slavers throwing people overboard to drown rather than face punishment from the squadron.

The Squadron in Action: HMS Black Joke

One of the most famous ships of the squadron was the HMS Black Joke. A former slave ship itself after being captured by the squadron in 1827, the Black Joke captured eleven slave ships in a single year.

In January 1829, the Black Joke, captained by Henry Downes, was in search of the infamous Spanish slave ship El Almirante. While off the coast of Lagos, Nigeria, Downes was notified of El Almirante’s presence and that it was taking on slaves destined for the Antilles. However, the slave ship’s captain, Damaso Forgannes, was also made aware of the presence of the Black Joke off the coast.

Black Joke intercepted El Almirante. However, the slave ship was an advanced ship with frightening speed. Furthermore, it commanded a crew of 80 men alongside 14 guns. In comparison, Black Joke had a crew 47 strong, with a mere two guns. A bold captain, Forgannes had no interest in running from Black Joke and instead attempted to engage in combat. El Almirante pursued Black Joke for almost an entire day. But, due to the unwavering determination of the Black Joke’s crew, the ship was able to keep out of range of the ship’s cannons.

However, at midday the next day, fearing they could not run any longer, Downes bravely decided to engage the slaver. The Black Joke sustained considerable fire from El Almirante for 45 minutes but managed to stay afloat. Then, despite being dramatically outmatched, the Black Joke managed to land critical shots at the slaver, resulting in significant structural damage and killing Captain Forgannes. Facing the risk of sinking, the remaining crew surrendered.

Victory for the Black Joke resulted in the freedom of 466 slaves aboard the El Almirante. Unfortunately, eleven enslaved people were killed in the fighting.

Expansion and US Contribution

By the mid-19th century, the West Africa Squadron readily expanded and improved its capabilities of capturing slave ships. Slavers had become increasingly aware of the risk of capture and, as such, began using faster ships in an attempt to evade the squadron. In response, the squadron adopted equally faster ships. By 1850, the squadron comprised 25 ships and 2,000 crewmen. Paddle steamers were also introduced to the squadron, which allowed rivers and shallow coastlines to be patrolled.

While the majority of anti-slavery patrols were conducted by the Royal Navy, the United States also contributed. The importation of enslaved people to the US was made illegal in 1807, though slave ownership was not officially ended until the end of the Civil War.

In 1819, the US established its own Africa Squadron, though it was much smaller in scale than the British operation. In 1842, Britain and the US signed the Webster-Ashburton Treaty to settle border disputes between the US and the British North American Territories. More importantly, as part of the treaty, the US and Britain agreed to end the slave trade on the seas. However, due to the much smaller scale of the US squadron’s operations, their overall effectiveness was limited. Reportedly, the US squadron only captured one slave ship on average per year. The US squadron patrolled the Atlantic for many decades. When the American Civil War erupted in 1861, President Lincoln recalled the squadron to support the Union war effort.

Impact and Legacy

The West Africa Squadron’s operations officially ended in 1867 when the squadron was incorporated into the Cape of Good Hope Station based in South Africa. Throughout its history, the squadron can be credited with the capture of 1,600 slave ships, which equates to roughly 6 to 10% of all slave ships crossing the Atlantic. Capturing slave ships also resulted in the freeing of an estimated 150,000 enslaved people.

Although the West Africa Squadron successfully contributed to the disruption of the transatlantic slave trade, it is important to examine the squadron within the wider historical context of the slave trade.

For three centuries, the British Empire was one of the largest slave trading nations and profited greatly through the reprehensible enslavement of the African People. Equally, the Royal Navy, though responsible for the West Africa Squadron, spent centuries protecting British slave ships and British slave economies in its colonies.

Although the West Africa Squadron should be rightfully congratulated for its role in disrupting the slave trade, the legacy of the squadron should not be used retrospectively to excuse or ignore Britain’s extensive participation in the slave trade.

The transatlantic slave trade exemplifies the inhumanity of humanity. It represents one of the most horrific, abhorrent periods of human history. Though the West Africa Squadron ultimately contributed to the end of the slave trade, it will never excuse Britain and the US’s longstanding participation and profit from the practice.